Not since the time the functionaries of the East India Company transformed themselves into Nabobs by siphoning off the exchequer of Bengal in the first decades after the Battle of Plassey has the province witnessed political corruption on such a grand scale. The public stupefaction that greeted the discovery of some Rs 50 crore of currency in two premises said to be owned by a friend of Partha Chatterjee, a top-ranking member of the Mamata Banerjee government and a stalwart of the All India Trinamul Congress, has jolted the politics of West Bengal. Its after-effects are likely to be far-reaching.

Three factors have contributed to the public trauma.

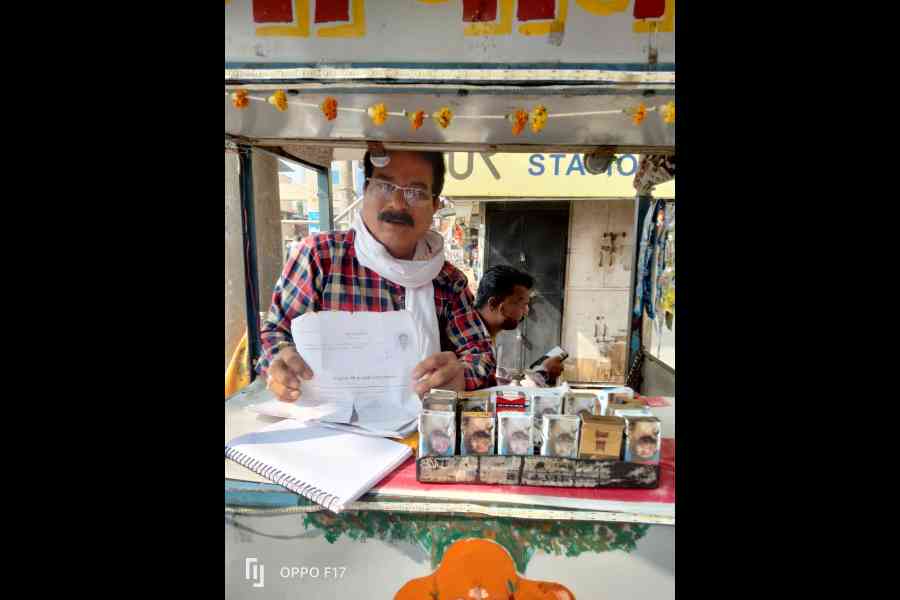

First, there is the sheer scale of the Enforcement Directorate’s discoveries. The belief that all politicians are in the business of amassing wealth that doesn’t find mention in their tax returns, if only to cover their political expenses, is all-pervasive throughout India. The moral judgment of the public is based on the quantum of dishonesty and the way the funding was effected. Pure anecdotal evidence suggests that the electorate is relatively charitable towards political functionaries who cream off a part of the profits of the better-off sections or even impose an unofficial ‘service charge’ on clearing transactions that have a potential of being blocked or delayed by the government. The indulgence turns to hostility when the extortion touches people who are not able to afford the levies. In the case of the disgraced Chatterjee, who has been dumped from the government and removed from his party following the ED raids, the defining image is the ‘mountain of notes’ that were casually stored in residential flats. It would not be an exaggeration to say that Bengal has not seen anything on this scale and the sensationalised media coverage has driven home the bewilderment very effectively.

Secondly, the ED investigations into the activities of Chatterjee stemmed from a high court ruling on irregularities in recruitment to educational institutions and to state government posts. The charge was that normal procedures and merit lists had been wilfully short-circuited to benefit people who were willing to pay an illegal consideration to secure government posts. The associated suggestion was that it was impossible to secure any state government employment without the payment of bribes, an impression furthered by the prolonged, ongoing dharna of those aspirants who felt they had been cheated out of jobs by those who had bribed their way. Moreover, these allegations of irregularities in the recruitment process didn’t surface abruptly with the case in the high court. The charges were part of the larger narrative targeting the Mamata Banerjee government for corrupt practices.

Politically what is significant is not that ‘cut money’ had become a buzzword in the state even before it became an issue in the assembly election of 2021. Far more damaging for the ruling AITC is the impression that the ‘mountain of notes’ was made up of small contributions by people who had gone beyond their means and even sold whatever meagre assets they had to bribe their way to jobs. The opprobrium in this case was attached not to the bribe-giver who was also cast as a victim of a corrupt system but to the bribe-takers, the ones who had devised this system to begin with.

What appears to have compounded the offence was the mounting evidence — mainly culled from a media having a field day — that the ousted big-wig of the ruling dispensation had used the proceeds of bribery to accumulate luxury properties. This dimension to the political scandal made it impossible for the AITC to maintain its earlier combative stance against ‘motivated’ Central agencies. It also made its earlier plea of collective cabinet responsibility difficult to carry over into the next round of battle.

Finally, while the Mamata Banerjee dispensation is hoping to insulate the party and the government from the wave of public disgust the Partha Chatterjee scandal has generated, it is proving very difficult. The fact that the manipulation of educational institutions and recruitment process in government jobs had undergone a serious distortion was already a part of the folklore well before the ED raids is well-known. The scale of the scam — estimated by some to be around Rs 1,200 crore — may have come as a surprise but not its existence. Along with charges of siphoning off MGNREGA funds and the misuse of grants for clubs, the Mamata Banerjee government was already reeling from charges of running a criminal enterprise under the garb of politics and governance. The Rs 50 crore cash mountain has merely confirmed popular suspicions.

The consequences are ominous for the state government. The plea that the awareness of the racket was confined to the minister, his accomplices, and a few close associates does not stand the glare of scrutiny. For a chief minister who is known to micro-manage all wings of the party and government, feigning ignorance is likely to be perceived as disingenuous. As a result, public pronouncements of zero tolerance of corruption and a reshuffle to discard the rotten apples may well be regarded as a case of too little, too late.

The question that the chief minister must now confront is the extent to which the present scam is likely to dent the government’s reputation irreparably. In the 2019 Lok Sabha election, the AITC was at the receiving end of rural fury over its high-handedness during the 2017 panchayat polls. It managed to recover ground in the assembly election two years later by consolidating Muslim votes in its favour and successfully projecting the Bharatiya Janata Party as a party of outsiders. The BJP also suffered from tactical miscalculations and organisational deficiencies, some of which came to the fore in the aftermath of the post-poll violence. Many of these problems persist, but over the past three months there have been two developments. First, the ruling party has become quite brazen in its high-handedness. And secondly, the BJP has discovered a leader it can rally behind as an alternative to Mamata Banerjee.

If these trends persist and acquire a life of their own, Bengal’s politics will experience a prolonged phase of turbulence.