Ask Molly. She knows. But even Molly, the faceless public face of the Central Intelligence Agency — why not Pretty Polly though? — has been unable to assure questioners that working from home is practicable for intelligence work. Spies, whether on the field or within closed doors, must always deliver their findings in a secure setting. This has become a problem for the intelligence establishment in the West, especially in Germany. Young persons, or ‘prospects’, being recruited for Bundesnachrichtendienst, its foreign intelligence agency, want to work from home. If that were not enough, they do not want to leave their cellphones behind when they go to work. That is, even if they do leave their favourite room, they will be carrying a surefire security threat with them. It is a little comic, at least for those who believe that spying is a nasty game causing innocent deaths in and out of war, but it is also an intriguing professional problem. It took root during the pandemic, when the comforts of working from home dawned on employees and its unexpected advantages on many employers. The BND chief has said that his organisation cannot offer certain things taken for granted today. The CIA and the almost mythical agencies of Britain have been more suave, suggesting they would find ways for greater ‘flexibility’.

Apart from security — a life-and-death matter — it would seem that cyber spying, tracking by metadata, drone visuals and so on have not made the dead drop or the brush pass irrelevant. And it is still as important to know more than one language, to create informers in the target country, to become someone else entirely if the field ‘task’ so demands and even live a life distanced from the family. This is really not a spare bedroom job, even if it is conducted just on the computer. Clearly patriotism, ideology or religious fervour are not what they were, for these, apparently, were some of the reasons behind spying. Strange, because they are on violent display everywhere outside the imaginably hushed corridors of intelligence agencies. If it is just a job like any other, then it can have many competitors. Love of adventure and secrecy is now probably channelled into video games; why bother to leave the room and risk life and limb in reality for that?

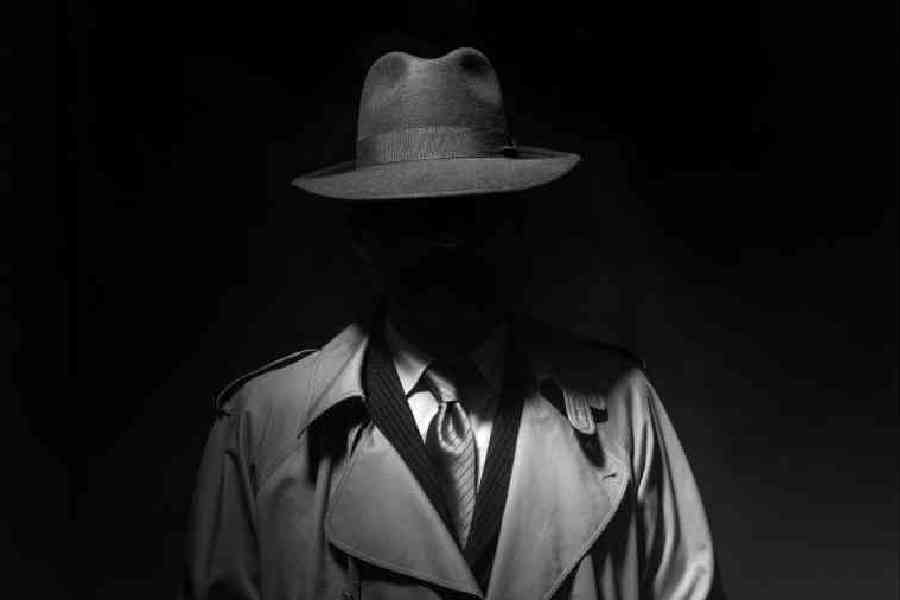

Not that the home cannot offer similar joys — the husband and wife in True Lies offer enormous fun. But on screen. Films love spies, whether it is the incorrigible James Bond — hat tipped to Ian Fleming of course — or anything from North by Northwest to Enemy of the State and all beside. Beyond the sound and fury of film, George Smiley and his men have probably done more to arouse interest in spying, and even he, as unlike Bond as a character may be, cannot work from home. So is greater flexibility possible — or enough — to make the job more enticing? Ask Molly.