We are living through a time when the founding ideals of the Indian republic are changing seismically. The cult of the leader overpowering the party at Central and state levels means that India today is a presidential system masquerading as a parliamentary democracy. The unashamed invocation of majoritarian prejudices and minority appeasement means India’s much-vaunted secularism is irrelevant in electoral politics. The profusion of love jihad laws across the country to widespread popular acclaim demonstrates how deeply vindictive society is.

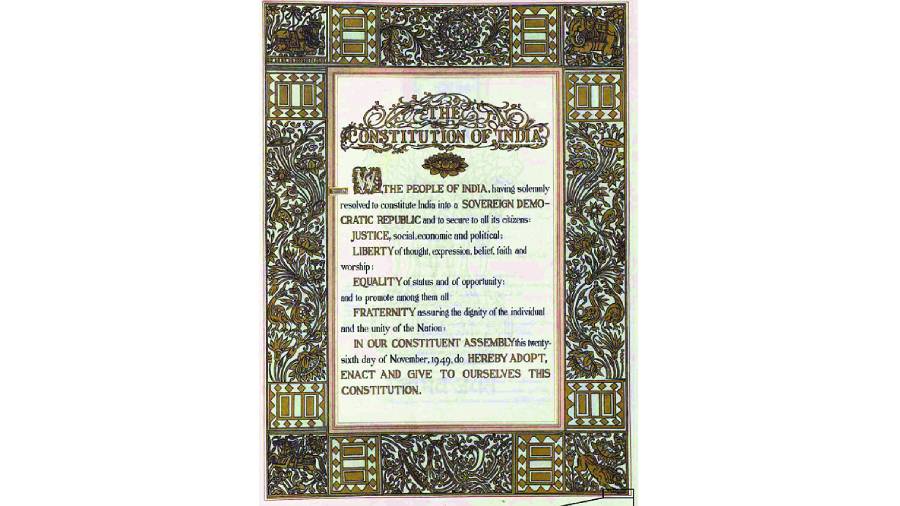

It is precisely to contain such changes that Constitutions are written. The founding fathers of the Constitution of India created a comprehensive document to account for and tackle a diversity of possible transgressions. The Constitution unequivocally set India on the path of liberal democracy secured through a parliamentary form of government, a federal structure, fundamental rights for every individual and a secular polity that treats all faiths equally. From the inauguration of the Constitution itself, many celebratory accounts of it have been written. These have both created and, in turn, fed off a lofty international image of India as the shining jewel of the global South, a colony that made it as a liberal democracy. While such accounts, with more than a kernel of truth, may have burnished India’s self-esteem as a new nation on the global stage, over time they have masked a fundamental reality — by and large, the Constitution does not matter in daily life or politics in India.

This is not to say that the Constitution is not a powerful symbolic presence. Prime Minister Narendra Modi regularly extols the foresight of B.R. Ambedkar in hard-coding reservation for scheduled castes and scheduled tribes in the Constitution; Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee excoriates the prime minister for shredding the secular fabric of the Constitution; a popular song in the lead-up to the Bengal elections ends with a rousing invocation of the Preamble to the Constitution; several lawyers and judges invoke the Constitution regularly in courts of law and in the media. Despite such seeming pervasiveness, the Constitution appears to be singularly failing at its core task of circumscribing the limits of acceptable politics.

Often a simple explanation has been offered for this — that the Bharatiya Janata Party and its ideological mentors in the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh have systematically denuded the Constitution because they had no part in drafting it. Historians of the RSS and political psychologists may be able to test the soundness of this claim. But there is a more uncomfortable truth that we have steadfastly refused to confront — that the Constitution itself has never seeped into the body politic in a way its drafters envisaged. This vulnerability dates back to the very making of the Constitution itself.

While many views have been expressed about the Constituent Assembly, two facts are relatively undisputed — first, the Assembly wasn’t an elected body and, consequently, operated in a different plane from mass politics; second, while most major political leaders were part of the Assembly (with the prominent exception of M.K. Gandhi), their dominant interests lay in the actual securing of freedom and then, after freedom was achieved, in governing the country. The task of drafting the Constitution was left primarily to Ambedkar and the Drafting Committee, a group dominated by lawyers who believed in establishing a liberal democratic order based on an enlightened European modernity. This is why Shankarrao Deo, Gandhian and member of the Constituent Assembly, wistfully remarked that its merits notwithstanding, “the Constitution can hardly be called the ‘child’ of the Indian Revolution.”

Although the Constitution contained a lot of promising material to build a modern India, it often appeared abstruse, unable to speak directly to the people. To resolve disputes it chose law and litigation over customary practices and mediation, guaranteed freedoms without recommending concomitant obligations, established a top-down governance structure firmly rejecting local self-government. These were conscious choices aligned with the modernizing mission of the drafters. But they were a continuation of choices that India’s colonial masters had made in the last two centuries, ignoring practices and forms of governance of older provenance. Many of these practices were retrograde and unsuited for incorporation in a democratic nation-state. But a refusal to seriously consider them while drafting the Constitution meant that the process would inevitably someday be seen as inauthentic.

The Constitution we gave to ourselves in 1950, distant as it may have been to reality, could have plausibly settled over time. In fact, it still might, as a lot of academic work seems to suggest. But today, 70 years on, the constitutional vision and the political reality of India have frontally collided. Such collisions are not surprising; in fact, it is precisely when these collisions occur that the Constitution as the highest normative expression of sovereignty is expected to get to work and overcome all challenges. But unlike several occasions in the past when the Constitution and its guardians have risen to the challenge of upholding the law in the face of overweening governments, this time it appears that the governments and a majority of the people are on one side and the Constitution on the other. This is a reactionary moment for inchoate political ideas, which have always simmered in the constitutional subterranean, to emerge into the mainstream.

Neither will this collision resolve itself quickly nor will its resolution lie in the realm of the law and the courts as the Constitution envisages. The fault lines are so numerous and deep that any resolution lies in the realm of ideas alone. These ideas are an augury of India’s approaching second constitutional moment — one that is truer to a people dismissive of checks and balances, god-fearing and religious, placing community and family over the individual, yet able to take such a reality and devise a constitutional order that works for all. There is some distance to travel before we reach such a moment but we are definitely headed there. Currently, though, we are at a phase in our constitutional life when we are desperate to shake off our Westminster detritus, yet unable to replace it with anything either original or empowering. Instead we have a perpetual state of polarization that promises to take India back in time, rejecting wholesale the modernizing vision of the founding fathers.

This is a rite of passage. It is our reactions to these developments that are critical — we can choose to hark back to the avowedly liberal ideals of the original constitutional founding and champion a resurrection. That would be easy to do but would equally be a misjudgment. A challenge to the Constitution cannot be answered by invoking the Constitution itself — that won’t get very far. Alternatively, we can choose a different starting point — the messy and incoherent amalgam of practices that together constitute political life in India. This amalgam has, over the centuries, been shaped by Manu and Ambedkar, Macaulay and Gandhi, Akbar and Krishnadevaraya, Nehru and Modi. This pastiche is our reality — the second coming of the Constitution needs to reflect it honestly, rising above it when it needs to.

The author is Research Director, Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy. Views are personal