I had a linguistics conference to attend in Wardha, Maharashtra. I took a cab from the Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar International Airport. For the next hour, the national highway tore through the biceps and triceps of the plateau — dry and rough and wanting in daubs of green.

On the appointed day, the vice-chancellor (VC) of the institute, or the kulpati — that is how he was addressed by those at the conference — delivered the welcome note. He spoke about the “oppressed” Indian languages and, thereafter, about the dominance of English. He said impassionedly, “We are not able to utter a single sentence in shuddh Hindi now. Forehead mein finger dabaiye. Yeh kaisi bhasha hai?” He was a man in pain, quite obviously.

Perhaps he hadn’t anticipated any rebuttals, but there were some. An IIT-Kanpur scholar made the point that anyone can mix and match languages; the phenomenon is called code switching. It is not a crime, not a problem, the scholar continued; in fact, not a point to make in a linguistics conference. Linguistics, after all, is the subject where diversities are celebrated. Once the IIT-Kanpur scholar had finished speaking, others in the audience approved audibly.

During lunch break, a group of scholars gathered around the kulpati. What were they saying? They were discussing how Hindi is a critically endangered language and an intervention is the need of the hour. And yet it is well-known that Hindi — or the dogged imposition of it — threatens to swallow countless regional dialects such as Awadhi, Bagheli, and Khariboli.

A professor at the institute, someone obviously in sync with the VC, spoke about how China promoted Mandarin through the vast regions of Xinjiang Uyghur, where once Turkish was spoken. He was upholding Communist China’s bullish efforts to iron out all linguistic and socio-cultural diversities. It brought to mind how the Soviet Union too promoted the Russian language through the central Asian and eastern European republics which it came to occupy.

The tenor of the conference, though, remained unaffected by these homogenising narratives. One paper in particular that stuck in my mind was titled “Manu Card” — I cannot remember the full title now. It was on the nativisation of the English language and the primary material was the menu cards of local eateries with their ingenious spellings.

In the evening, some of us explored the campus which was peppered with roads and hostels and auditoriums named after great personalities. A library named after polymath Rahul Sankrityayan, roads named after playwright Vijay Tendulkar and writer Munshi Premchand. Against these names that signify today, beyond anything, a spirit of benign tolerance, the kulpati’s agenda and diatribe seemed more than incongruous, ludicrous even.

Just outside the campus, there was a shop with a photocopy machine. On its walls was scribbled in black paint — Xerox Milel. “Milel” is Marathi for “available”. We had to photocopy our travel documents. And the thrust behind this enthusiasm was the lovely English word — reimbursement.

We were also enthusiastic about our food hunt. The hosts provided delectable fare, but it was vegetarian only. Rather uncharitably I thought it betrayed once again a lack of thought for a diverse palate. Non-vegetarian food is not permitted on campus. Right outside, there’s a dhaba that sells eggs — boiled, poached, yellow omelettes. But still, no meat.

After three days of soyabean, soyabean and more soyabean, we decided that egg was not enough. Some of us discovered a food stall selling chicken lollipops miles away from the campus, in Wardha city. Chewing on a chicken lollipop in a rebellious mood, as if the kulpati was watching me, it occurred to me — just as vegetarian food is a mean, so also is Hindi.

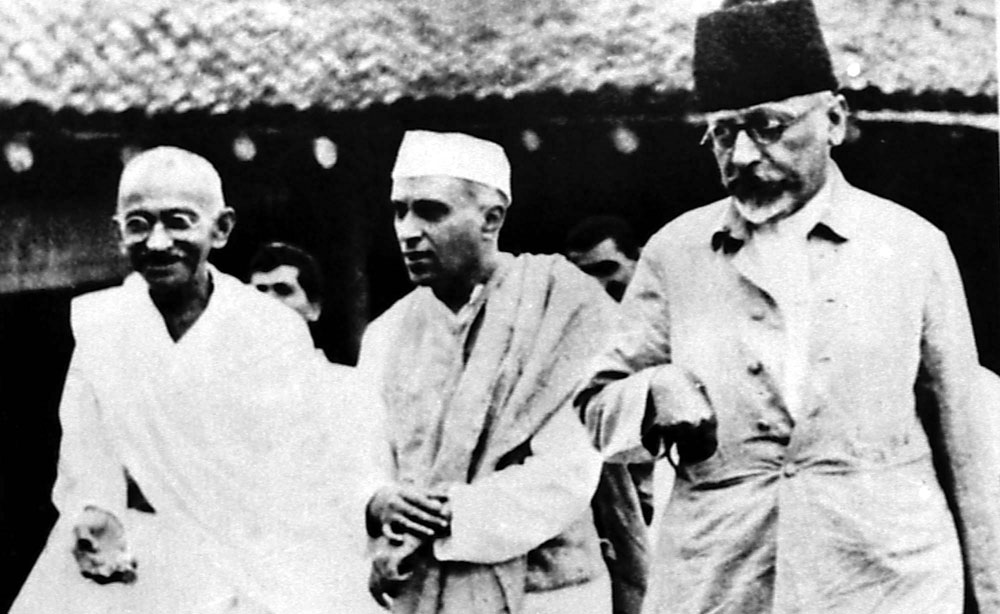

Wardha has a twin city and it is called Sevagram. Sevagram has a strong Gandhi connection. In the 1930s, after he left Sabarmati Ashram in Ahmedabad, this is where the Mahatma established another ashram.

Say what you may, but the air within the Sevagram ashram seemed to me that much more clear and pure. There was a general peace that imbued the place, a hum of tolerance hanging over. Women of a certain generation spun the charkha, and the men eschewed chairs and sat on the floor. One half expected to bump into the Mahatma at every turn — he is that alive in spirit, word and action.

And what do you know he might appear one day, if only to admonish the kulpati.