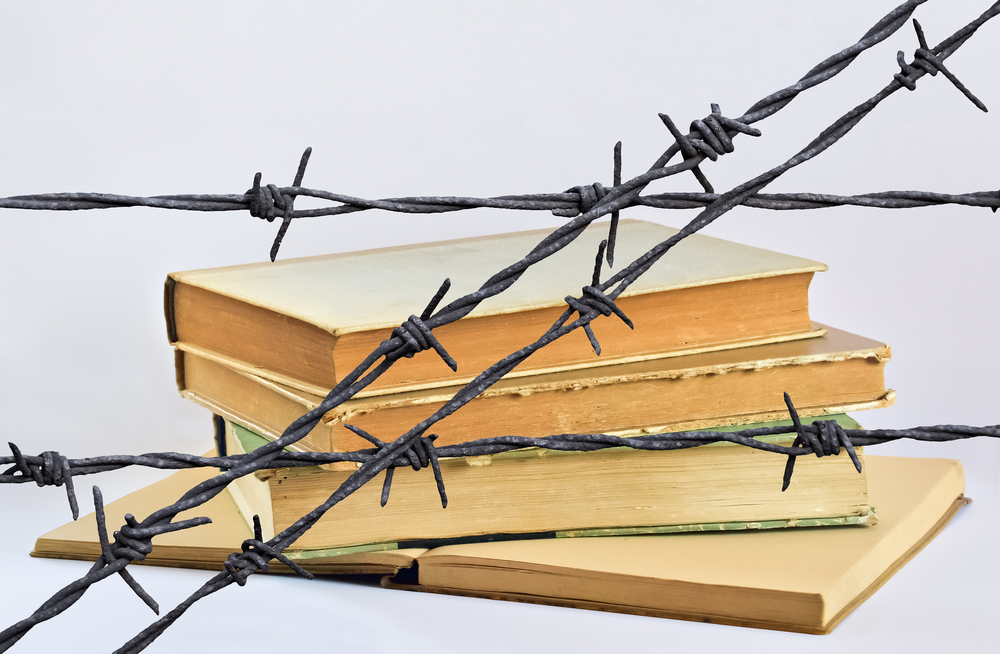

Tihar jail has a library with more than 10,000 books. Besides, it is well known that several prisoners from different prisons study and pass examinations. A popular degree is in law, for that allows inmates to be better equipped to follow their own case. Those convicted of grave crimes are not barred from reading or self-education. No country that claims to uphold human rights deprives prisoners of the right to self-improvement or the peaceful habit of reading. Yet Shalini Gera, an activist who went to visit the lawyer, Sudha Bharadwaj, imprisoned in Pune’s Yerwada jail since October 2018 for alleged links with the Communist Party of India (Maoist) in the — rather enigmatic — Elgaar Parishad-Bhima Koregaon case, had her birthday gift of two books returned. The prison official who gave the books back to Ms Gera asked her to get the court’s permission, in spite of the court having given permission for books to be given to the prisoner according to the jail manual. The prison official said that two books had already been allowed to Ms Bharadwaj and also to Shoma Sen, a teacher imprisoned in the same case. Apparently, prison officials are now in charge of deciding how much prisoners are allowed to read no matter what the courts might say.

The small incident brings up rather bigger questions. Are Ms Bharadwaj and those arrested in the same case under the same accusations of conspiring to topple the government and assassinating leading politicians by a hawala route while spreading a banned ideology and causing divisions and creating hatred in society considered criminals or political prisoners? It must be mentioned that so far no connection with anything culpable has been found in Ms Bharadwaj’s case, but she has not been allowed bail. No doubt the police have weighty evidence of this prisoner’s and the others’ guilt in all the charges enumerated. Is there a difference in the amount of reading matter to be allowed criminals and political prisoners? Or is it because John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath and, especially, Eric Hobsbawm’s Globalisation, Democracy and Terrorism, the books Ms Gera had brought, conjured up the bogey of the imagined deeds with which the prisoner is charged? One is fiction, and the other history. But rights are relative in New India: some have them, some cannot.