The run-up to the first anniversary of the United States of America’s pull out from Afghanistan has been dramatically punctuated by the targeted assassination in Kabul of Ayman al-Zawahiri, al Qaida’s head. This throws up numerous questions, not least about the continued interface between the Taliban government in Afghanistan and al Qaida. The US has certainly communicated that whether in Afghanistan or not, it has an undiminished capacity to target and eliminate enemies.

This tactical capacity does not address the question of what its twenty-year-long intervention in Afghanistan achieved, now that things in that country have come full circle. This first anniversary in Afghanistan — the Taliban retook Kabul on August 15, 2021— coincides with the 75th anniversary of decolonisation leading to freedom and Partition for a large part of South Asia. This moment rivets attention to the act of great power withdrawal itself.

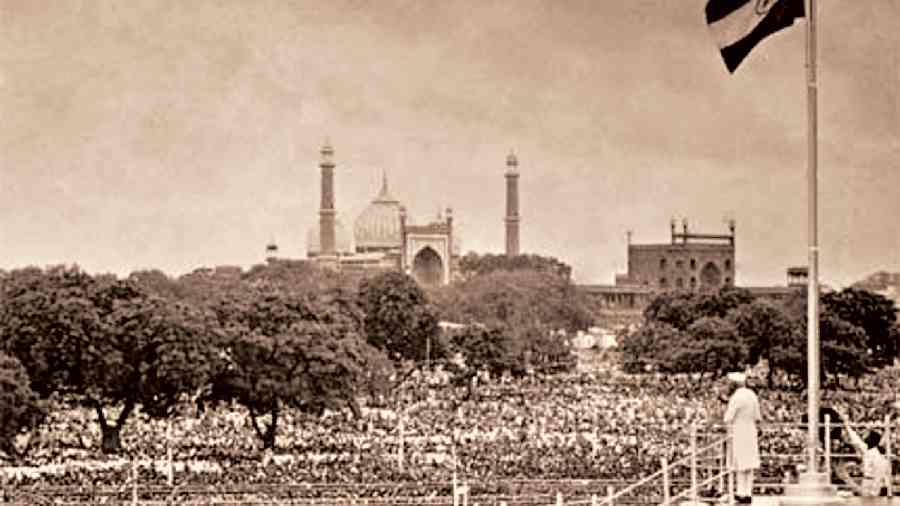

In India, there is near national consensus that the attainment of freedom was the culmination of a long and linear process of struggle. On the whole, this is seen as a long and glorious saga threaded with sacrifice, commitment and patriotism. An enterprise of many heroes and heroines, this is a story in which numerous individuals selflessly played their roles, small and big.

No such consensus or generally accepted explanation exists in India on Partition itself, the multiple massacres and the vast scale of ethnic cleansing that accompanied it notwithstanding. In Pakistan, the reading of Partition is simpler: it meant independence and liberation. It is, therefore, a totally distinct view unlike in India where the general view is to see it as a tragedy. In India, the absence of consensus over Partition and what led to it is not simply because of the emergence of Pakistan and the adversarial relationship that has persisted with it for 75 years. There are within India a multiplicity of views on who and what was responsible for the tragedy of Partition. To some the answer is simple: it was the British policy of divide and rule. Others believe that the Muslim League was most to blame for single-mindedly pursuing a policy of creating a nation based on faith. Yet others put the burden of responsibility on the Congress, particularly its right-wing, for not being more flexible in its dealing with the League.

For many, these narratives need to be animated by looking at individuals and their acts of omission and commission rather than at faceless organisations. M.A. Jinnah is, therefore, assigned the major responsibility whose pursuit of power and a separate country overrode all opposition. His Direct Action Day of August 16, 1946 was to many the last nail in the dream of a united India. In the focus on individuals, there is also a growing number who target Jawaharlal Nehru. His ego and his vanity, they argue, pushed India towards Partition. In particular, for example, his junking of the Cabinet Mission Plan in July 1946 made the situation irretrievable. This is not a new view but it has acquired more traction in recent years alongside other attempts to pull Nehru down from the high pedestal he has traditionally occupied. Critics also say Mahatma Gandhi’s decision to launch the Quit India movement in August 1942 gave the Muslim League the opportunity to expand while the Congress leadership was locked up in jail. Furthermore, Quit India, in this view, at a time when the Empire was in a life-anddeath struggle against Japan and Germany, irrevocably prejudiced the British against the Congress with fateful consequences for the unity of the country later. There are other explanations. Some are more cosmic and almost mirror the two-nation ideology that permeates Pakistan. In these, Partition was inevitable because the Muslims of the country never saw themselves as Indian and remained through their millennium plus history in India as foreigners.

Clearly, even after 75 years, each different view — there are others — has not cohered into a single explanation. But perhaps great power withdrawals from difficult situations have enough similarity to continue to provide insights.

In Afghanistan, the US announcement in April 2021 of a complete withdrawal by September that year — the 20th anniversary of 9/11 — precipitated a rout. War exhaustion, the realisation that US military presence was part of the problem rather than the solution and, finally, the sense that there was no domestic political mileage left in the US for the Afghanistan situation all contributed to what was a virtual throwing in of the towel and extricating in chaos. The announcement of withdrawal was expected but that it would be surgical in its completeness and then compressed into weeks was not.

In India in 1947, there were obvious differences. But the similarities stand out. Britain, bombed out and war exhausted, had other things on its mind than the Empire in India. Public opinion in India was impatient for change. In February 1947 came a long-expected announcement from the British government that its withdrawal from India would be completed by June 30, 1948. By early June, however, this date was pushed forward to August 15, 1947 — the deteriorating situation in India possibly led Viceroy Mountbatten and the British government to realise that exiting as soon as possible would absolve Britain from responsibility for the mayhem which they feared was imminent. In the compressed time frame, a division into two of a hitherto single entity, of its assets, the administration and the military were to be completed simultaneously with the transfer of power to Indian and Pakistani hands. More or less, everybody concerned acquiesced with the decision. It was a situation designed to end badly and it did.

Hasty departures mean there is something rotten in the State. Alongside strategic factors, tactical manoeuvring is important; and while empires are destined to disappear, the endgame by which they do remains of importance.

T.C.A. Raghavan is a former High Commissioner to Pakistan