The ongoing reportage on the cross-border skirmishing this last week has been bewildering. The average news-consuming citizen could be forgiven for wondering if anything he thought he knew about the Indian bombing of Balakot and Pakistan’s response actually happened or whether every event in this narrative was subject to continuous and radical revision.

The first impression anyone watching Indian news channels or reading its newspapers would have had of the Indian raid was this. Indian aircraft crossed the Line of Control for the first time since 1971. They didn’t merely venture into Pakistan- occupied Kashmir; they flew into undisputed Pakistani territory, into Balakot in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, within a hundred miles of Islamabad, and bombed a terrorist camp. Their attack left hundreds of terrorists dead. All Indian aircraft returned undamaged from their daring and unprecedented raid on Pakistan.

The main takeaway from this first draft of history was this: India had finally broken with the policy of restraint in the face of Pakistani provocation. Instead of being blackmailed into quiescence by Pakistan’s nuclear capability as Manmohan Singh’s government had been after the terrorist rampages of 2008, Narendra Modi’s regime had boldly chosen to draw new red lines. It had shown Pakistan’s deep State that India’s response to ISI-sponsored terror would not be constrained by precedent or convention, that India was willing to escalate the conflict in a precise and targeted way.

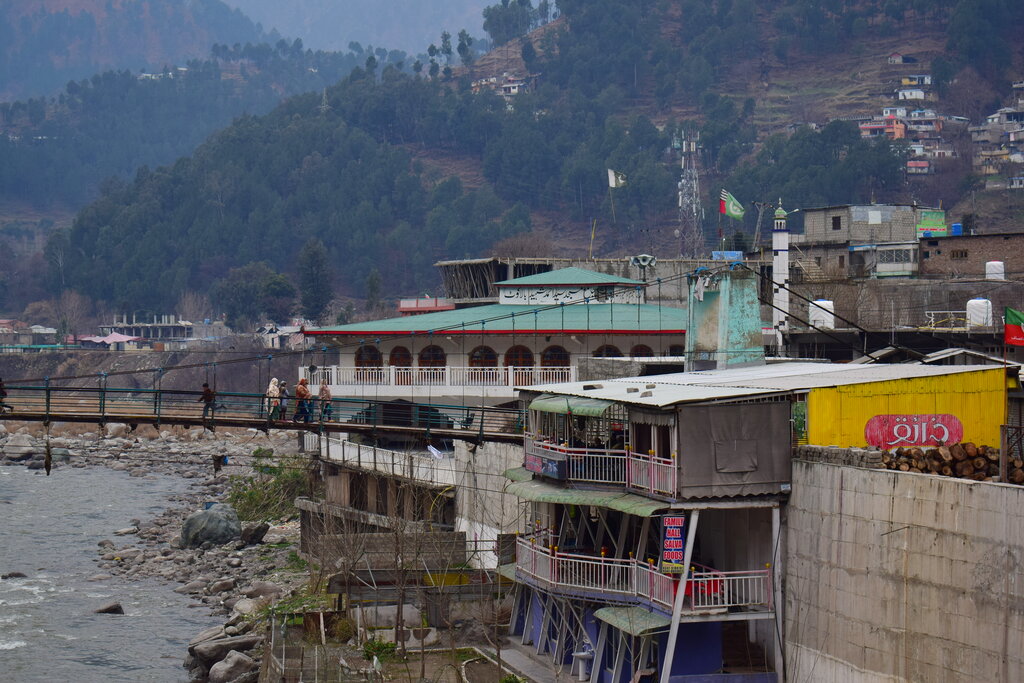

Pakistan denied the existence of such a camp or any casualties and showed photographs of a ploughed-up grove of pine trees, claiming that the swift response of its air force had forced Indian pilots to hastily dump their missiles on untenanted landscape. (Pakistan’s climate change minister, manfully striving to establish an equivalence of terror, subsequently accused India of bombing a forest reserve and being guilty of “eco-terrorism”.)

Gradually, through the fog generated by shock-jock boosterism, the outlines of another story became visible. In this version, the Indian government had never formally put a number on the terrorists killed. That had been a bit of colour attributed to ‘sources’ cited by patriotic news agencies. Nobody knew the extent of destruction or the number of casualties. This was either because satellite cameras had been obstructed by cloud cover or because the Pakistanis had restricted access to the camp and repaired the damage before it could be reported on, or because there had been no tenanted camp there in the first place.

Sober national security pundits dealt with this mutating story by encouraging their readers not to miss the wood for the trees. Whether India’s aircraft had killed militants or pine groves was irrelevant. The big picture was made up of India’s willingness to use air power to answer terrorism, the depth of the incursion and the indelible lesson the Pakistanis had been taught: namely, that India would not hesitate to strike Pakistan’s mainland if it didn’t mend its rogue ways. This was not exclusively a bhakt position; sage security experts, committed to the national interest, not Mr Modi’s electoral fortunes, saw the attack as a necessary, if long-deferred, lesson.

The Pakistani retaliation that followed almost immediately in broad daylight was first successfully repulsed by India’s news channels, with ranks of F-16s sent packing by the IAF’s MiG-21s. Pakistan had another story. Its spokespersons claimed that two Indian planes had been shot down and two pilots captured. After hours of silence, an official Indian statement acknowledged that one of the IAF’s pilots was missing. In the meantime, Pakistan had uploaded photos and videos of a captured pilot, Wing Commander Abhinandan Varthaman. Later in the day, Pakistan walked back its claim that it had captured two pilots but continued to maintain that it had shot down two Indian aircraft. Meanwhile Indian officials claimed that a MiG-21 had shot down an F-16 and its pilots had been seen parachuting into PoK.

So, from the precise and bloody destruction of a terror camp, the official version had shifted to the symbolic significance of raiding Pakistani territory (never mind the damage) and from there, in the face of the undeniable fact of Wing Commander Abhinandan’s capture, to a bid to establish parity in terms of planes lost. India hasn’t yet produced radar, video or AWACS evidence for its claim. The one factor in favour of the downed F-16 story is Pakistan’s own claim that it shot down two Indian planes. Since there is no evidence to show that India lost a second plane, it might just be the case that Pakistani spokesmen ran with the two-plane theory and then backtracked because one of the planes was theirs: an F-16 perhaps, or one of its Chinese fighters, the JF-17 Thunder.

Without concrete proof of camp destruction or the shooting down of the F-16, and faced with the embarrassment of a lost jet and a captured pilot, the Indian story shifted again. The return of Wing Commander Abhinandan became the new horizon. Politicians and anchors demanded his release... and received it. Imran Khan, keen to earn global brownie points by de-escalating and with the propaganda advantage of having made the only documented ‘kill’ in this skirmish, promptly announced Abhinandan’s release as a “gesture of peace”.

From exacting vengeance for the 40 Indian soldiers killed by terrorists to demanding the return of a single captured pilot, India’s strategic objectives seemed to shrink. The Indian government staged a novel media event where senior military officers appeared outside South Block, and took turns to hold the shards of an AMRAAM air-to-air missile. Since this was a missile only carried by F-16s, the point of this demonstration was to show that Pakistan had used these planes against India in combat in breach of its agreement with the US. From drawing bold new red lines to litigating the use of military hardware, the official narrative had run aground.

And then the story took an extraordinary turn. On March 1, a report in The Indian Express, quoting an anonymous Indian military official, claimed that the IAF hadn’t crossed the border at all. In this version of the story, Indian aircraft fired the Israeli missiles used for the strike from inside the LoC. If this is true, then the image conjured up in the minds of Indians following the news, of Mirages streaking deep into Pakistani airspace and startling the enemy, has to be replaced by the considerably more prosaic picture of Indian fighter aircraft acting as firing platforms inside Indian territory. This isn’t entirely the fault of the official narrative: a diet of second world war movies has us stuck in an obsolete past where planes have to be vertically above the ground that they target. But it does make you wonder what the sound and fury of the last week was actually about.

If the Indian air force claims to have attacked non-military targets from inside the LoC with little to show for it and if the Pakistan air force claims to have fired missiles from its side of the border and hit open ground, both sides can take issue with each other’s version of events, but to the wider world the exchange will seem like an expensive and dangerous charade pretending to be purposeful military action. Given that the one documented casualty was suffered by IAF (which, in turn, allowed the Pakistan military’s favoured client, Imran Khan, to act like a magnanimous statesman), it’s hard to know what the prime minister has to show for his vaunted boldness. A lost plane and a returned PoW seem to be the verifiable answers.

And what of our chickenhawk anchors? Edward Thompson, the great historian, once described an English journalist who specialized in publishing government leaks as “a kind of official urinal in which, side by side, high officials… stand patiently leaking in the public interest.” Marvellously apposite though this is, it’s wrong in one particular: in the Indian case, the high officials are redundant. The ‘journalists’ in question collect their leaks at one remove, from news agencies as independent and as committed to the truth as the Soviet TASS.