Gentleman’s game

One of my sillier theories is that England’s greatness as a nation is proportional to the number of pages given to cricket in national newspapers. But then there is something to be said about the civilising influence of cricket. Monday’s The Daily Telegraph had 11 pages on football and a page on cricket. Once upon a time, every county match was covered at length by the likes of the legendary Dickie Rutnagur. When I joined the paper, we had a night editor so crazy about the game that he put cricket news on page one. I was sounded out on whether I would like to become a cricket correspondent but I didn’t want to do it full time.

I wish I could have read a lyrical Neville Cardus-type piece on Pujara’s recent century, which the BBC mentioned briefly.

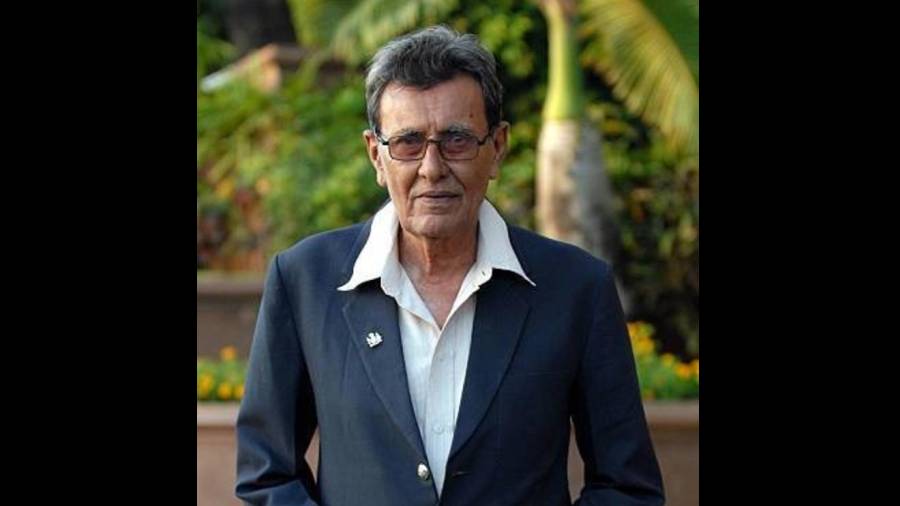

But perhaps the tributes to Salim Durani took people like Yusuf Hamied, chairman of Cipla, back to a bygone, gentler India. “I feel very sad, a friend has passed away,” Yusuf told me, adding, “Yes, I knew Salim Durani very well. He played for the Cipla cricket team.” Yusuf’s office sent me a couple of clippings from 1960. “A splendid innings by Salim Durrani [sic] for Cipla (against cementmen ACC),” read one report. “Salim Durrani, the overnight not out with 99, went on to score 180 before he fell to a splendid catch in the slips by R.G. Nadkarni,” read another. Yusuf didn’t see the match “because I was at Cambridge but I met Durani afterwards and we became good friends.”

Dangerous hobby

Listening to the distinguished British photographer, Martin Parr, talk to the presenter, John Wilson, on Radio 4’s This Cultural Life, I learnt that more people have died while taking selfies in India than in any other country. Wilson appeared taken aback: “Sorry, you mean people are dying because….they are unaware of some danger around them?” Parr, who has made a speciality of photographing Indians, assured Wilson: “Yes, they are about to fall off a cliff, or get trampled by a passing train, whatever….I therefore assumed that if India has more people dying of selfie, there are more people taking them than anywhere else in the world. I went to India and photographed a lot of people doing selfies to make this book called Death by Selfie.”

Enduring connections

Neil MacGregor, the former director of the British Museum, had presented a notable BBC Radio 4 series called A History of the World in 100 Objects. Similarly, behind a jade tea set that is currently on display at an exhibition at the Portland Gallery on the Welbeck estate in North Nottinghamshire hangs an important part of the story of Britain’s relationship with India.

The Dukes of Portland have owned Welbeck since 1607. The exhibition includes 500 treasures collected over more than 400 years by the Cavendish-Bentinck family, which has strong India connections. The jade tea set, the work of the master craftsman, Mahomet Amin, was brought to the UK from the splendid Delhi Durbar of 1903 by the sixth Duke and Duchess of Portland, who were personal guests of Edward VII, who was being proclaimed Emperor of India. He didn’t actually come, much to the disappointment of Lord Curzon, the then Viceroy of India, who had made the elaborate arrangements for the Durbar. “As long as we rule India, we are the greatest power in the world. If we lose it, we shall drop straightaway to a third-rate power,” declared Curzon.

Even Shashi Tharoor would have to admit that British rule was complex. The 6th Duke of Portland’s uncle, Lord William Bentinck, who had two stints in India and was the country’s first governor-general from 1828-35, abolished sati, suppressed female infanticide, and established English as the medium of instruction. He also founded the Medical College of Bengal, which became the prestigious Calcutta Medical College and sent countless doctors to the National Health Service.

Divided opinion

I think the expression, “dogs of war”, was first used by Shakespeare in Julius Caesar, by far my favourite play, partly because Father Cleary made us learn Mark Antony’s and others’ speeches by heart at St Xavier’s, Patna. So I am pleased to report that the Cambridge-educated Atri Banerjee has been given the responsibility of directing the Royal Shakespeare Company’s latest production of Julius Caesar at Stratford-upon-Avon before it embarks on a national tour. In his version, which I intend to catch, Brutus and Cassius are played by women while Caesar bleeds black blood, “possibly hinting at the oil greed of capitalism, which stains his assassins for the rest of the play” (The Guardian). Quentin Letts in The Times savaged the production as “unworthy of first-year drama students” but The Stage, a theatre journal, called it a “contemporary staging of Shakespeare... that’s as striking as it is sensitive”.