With apologies to Rupert Brooke, “If I should die, think only this of me:/ That there’s some corner of a foreign field/ That is for ever Bengal.” I refer, of course, to Raja Rammohan Roy, whose mausoleum in Arnos Vale Cemetery in Bristol received an honourable mention last week on BBC Radio 4’s Countryfile. The trigger words, ‘Arnos Vale’, made me listen carefully as the programme’s presenter, Helen Mark, explored the 45-acre cemetery, with its “most astonishing collection of memorials and headstones and architecture to remember the dead”.

Mark spoke to the tour guide, Alan Bambury, who told her that the cemetery, which started in the 1830s as an Arcadian garden, had “1,70,000 residents, as we like to call them, and 1,30,000 cremations, so there are about 3,00,000 souls in here”. Pausing before one mausoleum, an “extraordinary large one with a vast stone base with big columns and a top with a dome”, he explained: “This is probably the most famous — one that most Bristolians will actually know about even though the person in there isn’t a Bristolian and was only here for 10 days.”

“This is our Indian prince, Raja Rammohan Roy,” added Bambury. “He came to Bristol to see his friend, Lant Carpenter, and unfortunately he developed meningitis and died here. He is known as ‘the founder of modern India’. This one — out of all 55,000 graves, I would say — would be the most visited of all in the cemetery.” Roy was initially buried in the grounds of Beech House, Stapleton Grove, following his death on September 27, 1833, but his remains were reinterred on May 29, 1843 in Arnos Vale, his tomb funded by his friend and a co-founder of the Brahmo Samaj, Dwarkanath Tagore.

In 2007, the crumbling mausoleum was rescued with a $1,00,000 donation from Aditya Poddar, a Calcutta businessman, who felt that Scindia School, Gwalior, and St Xavier’s College had given him “a broad and secular vision of India”. I remember our trip to Arnos Vale where he told me: “It is a very proud heritage that we have — I want to contribute to that.”

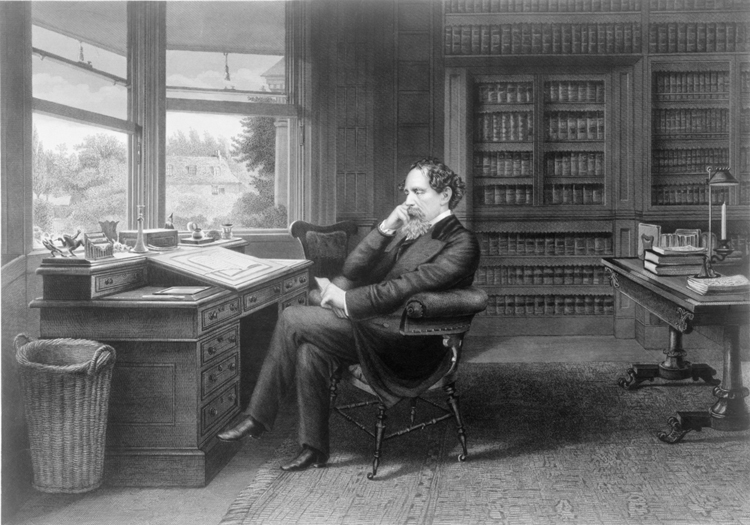

Charles Dickens helped introduce the way Christmas is now celebrated, especially in novels such as 'A Christmas Carol' (Shutterstock)

White Christmas

With less than a month to go before Christmas, attention has focused on how Charles Dickens helped introduce the way the festive season is now celebrated, especially in novels such as A Christmas Carol. A new exhibition, Beautiful Books: Dickens and the Business of Christmas, has just opened at 48, Doughty Street, which was the author’s first family home from March 1837 to December 1839, and which is now the Charles Dickens Museum. One of the highlights is the world’s first Christmas card from 1843.

At the museum, I talked to a leading expert on Dickens, Professor Simon Eliot from London University, who said: “Despite global warming, the picturesque scene of a white Christmas shows no signs of melting away.” He is not very keen on “wilful misrepresentations” of Dickens’s novels in modern film adaptations, such as The Personal History of David Copperfield, starring Dev Patel. “They can’t let Dickens alone,” he protested. “It’s a sort of imperialism. The present invades the past and plants its flag on it, ‘The past ought to be like this’.”

Ideal qualities

On the fast train back to London from the Kent seaside resort of Folkestone, I was very lucky to bump into Sir Anthony Seldon, the vice-chancellor of Buckingham University and the former headmaster of two well-known public schools, Brighton College and Wellington College. He is also one of Britain’s most distinguished historians, with more than 40 books to his name, including not-very-flattering political biographies of figures such as Margaret Thatcher, John Major, Tony Blair, Gordon Brown, David Cameron and, most recently, Theresa May.

I had spent the day at the Folkestone Literary Festival where Seldon had captivated a large audience with his entertaining analysis of the leadership qualities needed in a prime minister who could bring a very disunited kingdom together. I asked him what he made of Narendra Modi and former Indian prime ministers. What were the ideal qualities needed to bring together an India going through troubled times? He answered by saying that India was a country he knew tolerably well and he was indeed a regular practitioner of yoga and meditation.

As far as Britain was concerned, he was not overly optimistic. “We have had 299 years of prime ministers in Britain since Robert Walpole (1676-1745) — 54 prime ministers ago.” Since 1945, there were only two who could be described as “great”. One was Clement Attlee, who had “set in train the decolonisation — independence for India, obviously”. The other — and it was a “very controversial choice” — was Margaret Thatcher. “Somehow we are not bringing the right people into politics... also they come into office knowing absolutely nothing,” Seldon summed up.

On the list

After consulting 368 critics in 84 countries in the most comprehensive poll of its kind, BBC Culture has compiled a list of the “the 100 greatest films directed by women”. Mira Nair, currently filming an adaptation of Vikram Seth’s A Suitable Boy in India, has two entries: Monsoon Wedding (ranked 29th) and Salaam Bombay! (49th). The number one position goes to Jane Campion’s The Piano.

Queen Elizabeth visits the new headquarters of the Royal Philatelic Society London on November 26 (AP photo)

Stamp of approval

Queen Elizabeth delighted in seeing a rare Indian stamp for four annas (but now worth more than £1,00,000) from 1854 — it features an inverted head because of a printing error — when she visited the Royal Philatelic Society on Tuesday to mark its 150th anniversary and open its new building in London. After 67 years on the throne, the Queen has the stamp of approval from her subjects, which is more than can be said for her controversial second son, Prince Andrew.