From the late-1980s till the mid-1990s, when the State’s monopoly over television was broken, India witnessed a spate of extremely popular TV serials that — perhaps unwittingly — had a deep political impact. Leading the pack was, undoubtedly, Ramanand Sagar’s celebrated Ramayan, which enthralled mass audiences and even brought the country to a standstill each Sunday morning. Then there was B.R. Chopra’s version of the Mahabharat, which was a greater commercial success, and Chanakya and Chandrakanta, all of which had a lasting effect on the collective psyche of the people, particularly in the Hindi heartland.

The impact of Ramayan on society has been studied by scholars in view of its silent but decisive influence on the construction of a Hindu political consciousness. In his assessment of the serial, Arvind Rajagopal in Politics after Television: Hindu Nationalism and the Reshaping of the Public in India argued that “Viewers could understand the Ramayan as offering a way of talking not just about faith and the epic past, but about what kind of leadership a society required, and the mode of public engagement appropriate for its members.” At the same time, Ramayan brought out the deep schism between the English-educated elites who “saw in the serial’s popularity mainly the excess of tradition in a society that had moved ahead, rather than the prevalence of a still-relevant system of ideas…” and those blessed with more indigenous values. The serial “brought this division to the surface…, making elites aware of their cultural marginality, while emboldening the most articulate sections of orthodoxy with a sudden sense of their contemporaneity and relevance.”

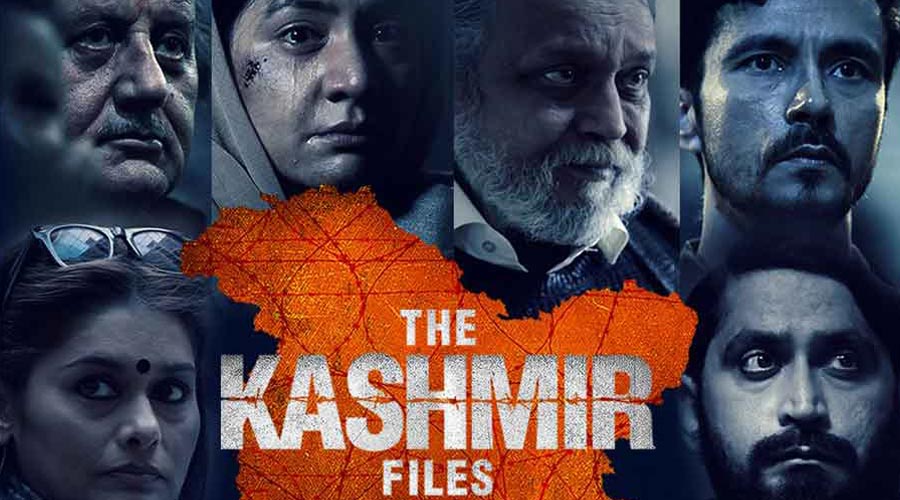

With the new, market-friendly India offering a huge range of choice and putting an end to the community watching that had added to the social impact of the Ramayan, the political impact of TV serials and films has been less decisive since the mid-1990s. This has now been broken by the spectacular success of Vivek Agnihotri’s The Kashmir Files centred on the forced exodus of the Pandits from the Kashmir Valley in 1990. It is not merely the staggering commercial success of a relatively low-budget film that is significant. Since its release, The Kashmir Files has become an important political talking point in the media, on social media, and even in the legislatures. Like in the reactions to the Ramayan, the film has triggered a sharp polarization between those who are aghast at the way the Hindu minority in the Kashmir Valley was subjected to ethnic cleansing and those who insist that the main purpose of Agnihotri was to fan the anti-Muslim flame and bolster the Hindu nationalism of the Bharatiya Janata Party. The battle has played out quite openly, and in different ways. There have been allegations that activists of the ruling Trinamul Congress have arm-twisted cinema halls in Calcutta to stop further screening of the film. And in Delhi, the BJP and the Aam Aadmi Party are at loggerheads over the caustic comments of Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal on the demand for granting tax-free status to The Kashmir Files. Whereas in the case of the Ramayan, both the Congress and the BJP attempted to appropriate the explosion of Hindu sentiment — the Congress came out second-best — in the case of the kerfuffle over the treatment of Kashmiri Pandits, all the political dividends have been mopped up by the BJP.

Political returns were, however, a consequence of the huge popularity of The Kashmir Files and the undeniable fact that the theme of the film has become the subject of conversation. This isn’t necessarily because of the depiction of violence. Other films, particularly those made in the United States of America, have scenes that are far more violent than anything made by Indian filmmakers who are too conscious of the sensitivities of the censors. In my view, two factors contributed to the curiosity over the film and its profound impact.

The first is the stark depiction of a very unfortunate chapter in the troubled history of Jammu and Kashmir. The grim truth about the expulsion of a small, but influential community — the Kashmiri Pandits — in January 1990 was known in select circles at that time, not least because the BJP made it a big campaign issue against the V.P. Singh government. However, since the expulsions took place before India witnessed the epidemic of TV news channels, its impact beyond Jammu was not commensurate with the scale of the tragedy. In effect, the expulsion of Kashmiri Hindus existed as a footnote to the larger turbulence in the state. The Kashmir Files has put the issue on centre stage and told Indians what they didn’t choose to know in 1990. Having now discovered what happened, there is a belated sense of outrage.

Secondly, the depiction of communal tensions in films and on TV has hitherto been guarded and largely sanitized. In The Kashmir Files, cinema audiences were exposed to the full extent of the religion-based separatism that was a feature of the Kashmir insurgency. Agnihotri didn’t pull his punches. The opening scenes of The Kashmir Files are all about gun-wielding mobs demanding that the local Hindus either convert, depart or die. This fanatical intolerance of their Hindu neighbours found expression in the explicit dialogues of the film. In another age, the censors would probably have refused to clear the film for fear that it would upset a ‘secular’ equilibrium based on the denial of the rough edges of religiosity. Consequently, many viewers were, perhaps for the first time, exposed to the inflammatory hate rhetoric that, alas, is a feature of radical religious mobilization all over the world, not least in South Asia. The film also exposed the duplicitous nature of the uber liberalism that prevails in many of India’s campuses. In line with Agnihotri’s ongoing crusade against ‘Urban Naxals’, it suggested definite links between Islamist separatism and other plots for the vivisection of India.

The Kashmir Files was nominally about gruesome events that played out three decades ago. Its impact, however, owed entirely to audiences being able to relate history with a world they see around them. The impact of this film may be impossible to quantify but is certain to be profound.