Since 1858, when the responsibility of running the British Indian Empire passed to the Crown, the defence of the frontiers dominated the strategic thinking of the Government of India. Throughout much of the late 19th century, this preoccupation was subsumed within the parameters of the Great Game, the romantic shorthand for the shadow-boxing that marked Anglo-Russian rivalry in Asia. For imperial strategists, the outer reaches of the influence of the British Indian Empire were imagined to extend from Singapore in the east to Aden and the Suez Canal in the west.

An important element of this strategy was the creation of either a friendly or at least a non-hostile buffer zone that would separate India from the rival Big Power. The logic wasn’t specious. In 1846, there was a distance of 2,000 miles between British India and Russia. However, by 1885, the gap was less than 500 miles. What now sometimes appears as an idiosyncratic military mission by Colonel Younghusband to Lhasa in 1904 makes more sense when viewed as an important element of creating a buffer zone between India and China. The firm delineation of India’s frontiers — the Durand Line between India and Afghanistan and the McMahon Line between India and Tibet/China in the east — was an important part of the defence of India.

There were two important changes after Independence in 1947. Firstly, the western frontiers of India were redrawn by the Radcliffe Line. This involved the loss of the buffer in Afghanistan and led to the creation of a hostile neighbour on India’s doorstep. The dispute over Jammu and Kashmir complicated the situation and ensured a state of permanent military preparedness within India. In the mid-1990s, Pakistan acquired greater ‘strategic depth’ through its control over Taliban-ruled Afghanistan, an advantage it has regained after a 20-year interregnum. An additional complication was created by Cold War strategists who favoured a pro-Pakistan tilt by the United States of America to offset what they felt was India’s partiality towards the Soviet Union. Consequently, the focus often shifted from the defence of India to India’s relative insignificance in the global chess game — a development that was also moulded by India’s inability to realize its own potential in the economic sphere.

Secondly, China’s assumption of military control over Tibet in 1950 lost India its buffer in the east. The mistaken belief that China was a benign and friendly power prompted Jawaharlal Nehru to take his eye off the ball and roll back the Indian presence in Kashgar, Bokhara and Lhasa. It was more than just the closure of Indian missions that had existed during the high noon of the raj. The truncation of India’s influence in Central Asia was an aspect of Nehru attaching greater priority to personalized diplomacy over reinforcing India’s pre-existing strategic clout. Whereas China after the Communist revolution in 1949 embraced an assertive nationalism that had its origins in traditional Middle Kingdom doctrines, India repudiated the India-centric strategic thinking that was a hallmark of the raj after the 1880s. India tried to wallow in its ‘soft power’, not as an appendage to larger ‘hard power’ designs but as the mainstay of its approach to both the neighbourhood and the world. Even in hindsight, Nehru’s outright rejection of an American offer to replace the dispossessed Kuomintang regime in Taiwan with a permanent place for India in the United Nations Security Council makes no sense.

Even S. Gopal — Nehru’s most sympathetic ‘official’ biographer — is harsh on Nehru’s astonishing woolliness: “[Nehru] hoped fondly that friendship with the new China would not only maintain peace in Asia but start a new phase in world affairs, with Asia giving the lead in a more humane... [and] sophisticated diplomacy. The Chinese took advantage of this and exploited India’s goodwill while placing little trust in her. The basic challenge between India and China, as China never seemed to forget and Nehru could not finally help recognizing, ran along the spine of Asia.”

The 1962 military debacle in the Himalayas was a late wake-up call. Yet the defeat wasn’t accompanied by the requisite capacity building, particularly in the economic sphere. Thus, while China single-mindedly proceeded to overcome past disabilities and re-forge itself as a global power after 1979, India was painfully slow to get off the blocks. In a recent work on Indian diplomacy during the Bangladesh crisis of 1971 that draws on hitherto untapped sources, Chandrasekhar Dasgupta has revealed the huge reluctance of the external affairs establishment towards steps that would entail any solution to the crisis in East Pakistan outside the framework of a united Pakistan. It was the pig-headedness of President Yahya Khan and the preference for a military solution that tilted the balance in favour of an independent Bangladesh.

The past 25 years have witnessed multiplying challenges to India’s national security. There are two dimensions to the threat.

The first is the ideological challenge of radical Islamism that is intoxicated by the belief that its faith can prevail over sophisticated arms and the enormous material resources of the world’s big powers. The Taliban — or, for that matter, their more radical cousin, the Islamic State — are only nominally national movements. Radical Islamism has targeted Muslim communities, cutting across national boundaries, with the promise of a divinely-blessed good life. Its organizational structures may well be uneven but its potential to destabilize the whole of Central and South Asia, including India, is unlimited. The whole world is still grappling with the problem of how it can be defeated at the level of ideas.

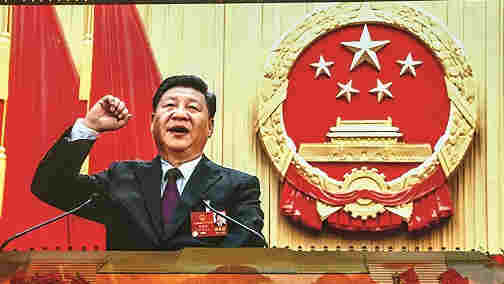

The second challenge — which, too, is a global phenomenon — facing India is the threat of Chinese hegemonism. If radical Islamism seeks to motivate people by invoking god, China is overflowing with its sheer audacity of vision. After the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, the Soviet Union had given a call for world revolution and motivated a large number of people into believing in its possibility. China’s leadership isn’t too bothered with the ‘struggling masses’; it seeks to influence the political classes into reposing their faith in China’s ability to dole out credit and technology, buy influence and even offer military assistance in return for ‘concessions’ — incorporation into a China-controlled world economic order, the Belt and Road Initiative. China is creating a 21st-century version of the Middle Kingdom that involves vassal states acknowledging its hegemonism and allowing it unhindered passage in return for a role in the exercise.

India has so far resisted the bait and, consequently, earned China’s displeasure in different ways, including military pressure and the encouragement of Pakistan, diplomatically and militarily. However, it is clear that this is a battle India cannot fight alone. Apart from the fact that China’s economy dwarfs that of India, Beijing is today a world leader in technology and international trade. An isolationist India that has retreated into its shell will suit China admirably. What will not suit it is an India that has entered into a strategic relationship with countries that have similar vulnerabilities. The Quad is as yet an untested investment in the future involving India, Australia, Japan and the US. It is Asia-focused and technology-focused, but will probably have an arms-length relationship with the Aukus military grouping that seeks to challenge China’s bid to control the Indo-Pacific. India is understandably cautious about over-committing itself to anti-China blocs because it is the only country with which China has a common and disputed border. The longer-term approach to national security must involve rapid capacity building on economic and military fronts. But additionally, it involves shunning mediocrity and relentlessly embracing the quest for excellence. The big challenge is to reconcile these challenges with preserving a vibrant democratic culture — something that China doesn’t want to know.