Marc Bloch, Christopher Hill, E.P. Thompson, D.D. Kosambi prepare to receive an honoured guest as Ranajit Guha is laid to rest. Let the Bengali vessel lie emptied of its history and learning.

Some readers will immediately pick up that the above paragraph echoes (with some obvious alterations) a verse from W.H. Auden’s "In Memory of W.B. Yeats’’. For those of us who loved Ranajit Guha (born 23 May 1923; died 28 April 2023) and/or were influenced by his writings and his insights, the sense of loss is as colossal as what Auden felt when Yeats died in January 1939. It is not that Ranajit Guha’s death was unexpected. He was in his hundredth year and had been unwell for some time. But, death, in spite of its inevitability, leaves us invariably with a sense of unpreparedness. Thus it was: a sense of profound loss that robbed me of sleep when the news of his end came around midnight on 28 April. A permanent settlement if ever there was one. An ineradicable line drawn.

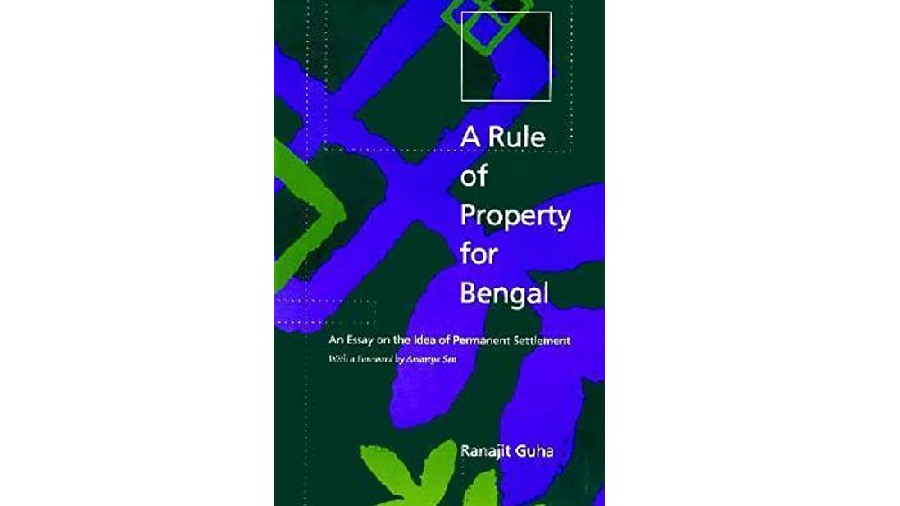

Ranajit Guha had entered my intellectual landscape at least a decade before I first met him. My intellectual introduction to him was through his first book, A Rule of Property for Bengal. I can distinctly recall when I first heard of the book. It was in Barun De’s office at the Indian Institute of Management then located in Emerald Bower on the Barrackpore Trunk Road. I was then a first year History Honours student at Presidency College. It was the autumn of 1970 and the college had been shut down sine die because of political violence. Barun De had taken on the task of educating me in the reading of history. That morning among the many books he specified I must read was this book by Ranajit Guha. A few weeks later my teacher Ashin Das Gupta, a historian whose approach to the subject and to its teaching was very different from De’s, mentioned the book and suggested that I should read it. I could not resist two such recommendations from two mentors. I asked Barun De where I could get hold of a copy; he lent me his and I read it in a kind of daze.

There are some first impressions that remain. The Preface was written in the third person ("In his early youth the author, like many others of his generation in Bengal, grew up in the shadow of the Permanent Settlement.’’). The subtitle of the book, "An Essay on the Idea of Permanent Settlement’’ puzzled me. I knew of the Permanent Settlement as an important, if pivotal, chapter of Bengal’s agrarian history. Agrarian history brought to my mind books like those written by Irfan Habib or N.K. Sinha. What had ideas got to do with agrarian history? I started reading the book with a sense of awe, puzzlement and trepidation. I was bowled over by it not because I understood everything in it let alone comprehending the significance of its arguments. I was overwhelmed by how well the book was written, by the sheer beauty and euphony of Ranajit Guha’s prose. So many of Guha’s sentences and turns of phrase became embedded in my memory ("… made it erratic like a child’s first attack on a meccano set’’; "Pioneers seldom make a virtue of patience’’ and so on). Could history really be written with such style and grace, I asked myself. I continue to believe that stylistically it is the best written book on any aspect of Indian history. Through subsequent readings, I also came to recognize its historiographical originality and significance.

When the book was conceptualized and written (first an incomplete version in Bengali in the mid-1950s and then in English and published by Mouton and Company in 1963), historians did not consider ideas to be a factor in the making of British policy in the colonies. Policies were made through pressures of factions formed by self-interested individuals. Guha’s book broke the shackles of this mindless history. He showed how ideas like mercantilism, free trade and physiocracy had influenced the formulation of a major agrarian policy in late 18th century Bengal. He argued that the priorities of colonialism – the quest for expanding markets – had divorced the original idea of the policy from its outcome. The zamindar who was supposed to have become through the magic touch of property an improving capitalist farmer had turned out to be its exact opposite – a parasitic absentee landlord.

Far in advance of his time, Guha had demonstrated how to study the history of an idea. He had done something more --- and this is where A Rule of Property transcends its own historiographical context. In his Preface to the second edition of the book (1981), Guha drew his readers’ attention to this aspect. He wrote, "It [this book] addresses itself to the question of colonialist knowledge.’’ (italics in original) The book, it was Guha’s belief, by tracing the intellectual lineage of the Permanent Settlement to physiocratic thought, had gone back to the very beginning of Political Economy. Physiocracy was a critique of feudalism in France and had thus helped to undermine the ancien regime. But when Britain, "the most advanced capitalist power of that age’’ had grafted physiocracy onto India, physiocracy had become its own caricature: "it became instrumental in building a neo-feudal organization of landed property and in the absorption and reproduction of pre-capitalist elements in a colonial regime.’’ Guha reiterated the point that: "a typically bourgeois form of knowledge was bent backwards to adjust itself to the relations of power in a semi-feudal society’’ and it was this "epistemological paradox’’ that he had attempted to trace and explain through the idea of the Permanent Settlement. There were other bodies of knowledge, as Guha noted, which had been imported into India during British rule --- knowledge that the bourgeoisie in the West had used in its struggle against feudalism. But in India those bodies of knowledge "suffered a sea change’’ as the colonial rulers sought to find a social base for their power in an alien land.

Through these words written at the beginning of the 1980s, Guha was alerting his readers to his new intellectual concerns. These were to be manifest in his second book Elementary Aspects of Peasant Insurgency in Colonial India (1983) and the first volumes of Subaltern Studies – works that would make Guha internationally famous. One crucial aspect of Elementary Aspects and of the Subaltern Studies project was an analysis of the relations of power in colonial India. The study of power and dominance in the rural world carried for Guha resonances from his childhood. In the only fragmentary autobiographical account Guha wrote he had remembered how there were groups of people around him and his family, and these included some of his playmates, who were invariably referred to as praja or subjects; and the latter referred to Guha’s family (including the child Ranajit) as manib or master. The word praja had become an integral part of Guha’s memory --- a sign of the power and dominance that zamindars, products one and all of the Permanent Settlement, had enjoyed and exercised in the rural world of Bengal. When he studied the idea of the Permanent Settlement, Guha saw for himself the contrast between the original vision of the improving capitalist landlord and the reality of the parasitic zamindar who exercised dominance in Bengal. His work on peasant insurgency and the politics of the subaltern classes would have this dominance as its context and even perhaps its raison d’ etre. The dominance of the ruling elite as well as that of the Indian elite became a major theme of Guha’s work. Elites in India found hegemony to be perpetually elusive because, as he put it, "Capitalism which had built up its hegemony in Europe by using the sharp end of Reason found it convenient to subjugate the peoples of the East by wielding the blunt head.’’

Integral to almost everything that Guha wrote was the idea of a critique – radical doubt regarding all forms of received wisdom. His critique of colonial and elite dominance led him to ask the question: could there be an Indian history of India? A mode of history writing that would be free from the disciplinary boundaries fashioned by western historiography, especially colonialist historiography. Such questions took him to the study of literature and texts. One product of this line of enquiry was History at the Limit of World-History, the last book in English that he wrote. In this work which many of his most loyal admirers found to be almost too metaphysical Guha was urging his readers to think differently about the muse of Clio – in fact to see it as a muse rather than as a discipline and to locate it, as Tagore did, in the quotidian practices of ordinary individuals. The idea of critique made him read Orwell’s "Shooting an Elephant’’ as an articulation of the anxiety of empire caught though it was in a mere blink. He read Conrad’s Heart of Darkness almost as a complement to the empire’s dominance without hegemony since at every bend of the river that took Marlow to the beginning of time there was incomprehension precisely where the jungle began. The incomprehensible could only be ruled through coercion and violence which were at the heart of that uncanny entity called empire. Guha taught his students and his readers to read texts against their grain to gouge out answers that were not apparently visible. From contextualizing a mere fragment of a court testimony, Guha demonstrated, in the essay, "Chandra’s Death’’, through an enviable deployment of the historian’s craft how it was possible to understand the structures of sexual exploitation, caste discrimination and gender solidarity that resulted in the death of a lower caste woman in-mid 19th century rural Bengal.

Towards the last phase of his life, these questions led him to what had always been the love of his life – the Bengali language and Bengali literature. He decided to write only in Bengali and wrote on Rammohun, on Bankim, on Tagore and on contemporary Bengali poets. He brought to these writings his immense erudition illuminating the works of these writers by raising epistemological and even psychoanalytical issues.

Ranajit Guha wrote all his Bengali books and essays sitting in his home in Vienna. Visiting him and his wife, Mechthild, there, every year before the pandemic, my wife and I were often reminded of another set of lines from Auden: "Towards the end he sailed into an extraordinary mildness,/And anchored in his house and reached his wife/And rode within the harbour of her hand…’’

In many ways, Ranajit Guha’s intellectual quest, in spite of his long and fruitful life, was a journey unfinished. But I think that is how he would have wanted it to be. He had questioned, he had taught us to ask questions to which often there are no adequate and comfortable answers. That is his legacy. The angel of doubt bore him to the enchanted Vienna Woods.

Rudrangshu Mukherjee is Chancellor and Professor of History at Ashoka University