There is an interesting commonality in the results should you be searching such phrases on Google as fear in Hungary, fear in Brazil, fear in the Philippines or fear in India. The landing page inevitably points to local events in these economies that seem to suggest a climate of fear, rising identity politics driving such a climate, and populist leaders being the architects of such environments.

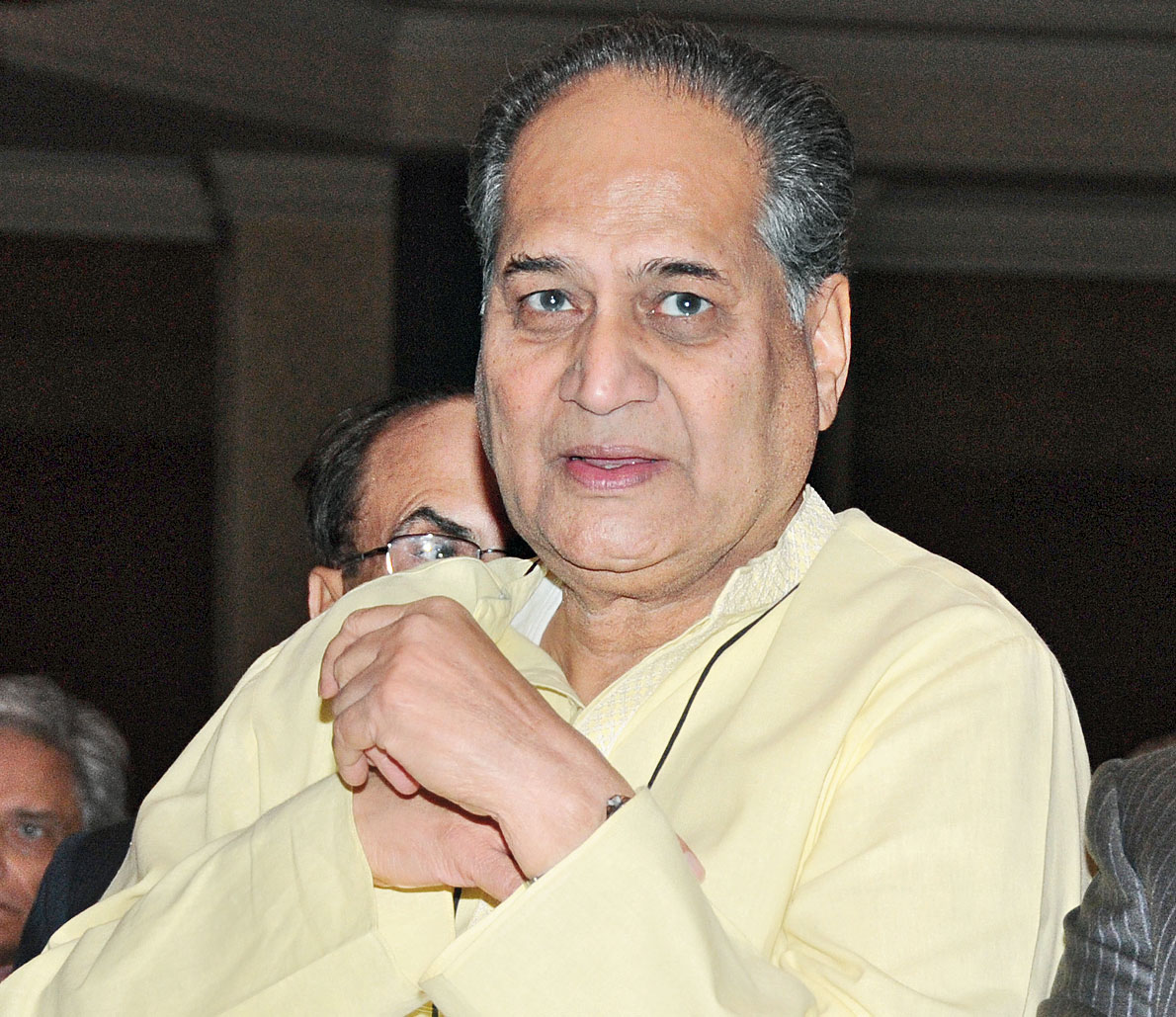

This raises the question as to how, if at all, fear and a lack of trust can impact economic growth of nations. With Manmohan Singh, the former prime minister, urging the current Indian government to restore social trust to revive the economy and Rahul Bajaj pointing out publicly about an environment of fear, it is worth pondering what evidence has to say from past works in economics, political science and sociology on this relationship.

Moses Abramovitz and Paul David in their essay in The Mosaic of Economic Growth were among the early scholars embracing the idea of social capital and trust in influencing economic transactions and growth. However, they also pointed to the difficulty in measuring trust and relating it causally to economic growth on account of data challenges. The Abramovitz and David arguments extended the earlier, ambitious, empirical work of Irma Adelman and Cynthia Morris who investigated the relationship between social development (as a proxy for trust along with political variables) and economic growth with factor analysis conducted in a sample of 74 developing countries between 1957 and 1962. They found that social development matters. They were, however, basic in their analysis as improved datasets and causal econometric techniques arrived in the subsequent decades along with discussions on the channels through which societal trust may actually impact growth.

In his paper, “Economic Growth and Social Capital” (2000), Paul Whiteley made important advances. He noted that increased levels of trust reduce transaction costs, enable actors to solve collective action problems (smog, carbon dioxide emissions or overfishing) and bring down monitoring costs by softening principal-agent problems. Whiteley’s ideas found resonance in a paper by Robert Solow, a Nobel laureate economist, on social capital and economic growth and were also consistent with the ideas of Elinor Ostrom, a co-recipient of the Nobel in economic sciences in 2009. Ostrom was, in fact, provocative in a 1999 article, asking if social capital is a fad or a fundamental concept and went on to reason that it is the latter.

This then brings us to what modern applied economists have to say on fear, trust and economic growth. The findings are unequivocal, especially with the use of new data sources like the World Values Survey, which measures societal trust over waves and representative cross-sections of households across the world. Stephen Knack and Philip Keefer, and then Paul Zak and Knack, show that trust matters in economic growth in large-sample, cross-country studies varying over time.

Some recent studies have, however, raised concerns about using the World Values Survey. Others have urged carefully examining the endogeneity of trust with economic growth (that is, growth impacting trust rather than the other way round) and have advocated shocks to trust (perhaps the Indian demonetization experience can be one such) to make more causal inferences. Also, the roles of culture and corruption from sociology and political science raise some mechanism discussions here.

The last word on fear, trust and economic growth seems not to have been completely written. There may be boundary conditions and diminishing returns from trust in a priori high-trust societies in comparison to others. Inequality, social media and smartphones may be ushering in new complexities to this relationship. Further, there may also be a role of ideology and identity politics that may point to new avenues for investigating alternative channels. In talking about social trust and the environment of fear, Singh and Bajaj may have done a service to social science researchers.