Into the fifth month now and it still seems that there’s no end in sight to the Manipur nightmare, which began on May 3, and has led to some of the worst bloodletting between the Kuki-Zo community and the Meiteis. After the initial days of complete mayhem, there have been short spells of quiet raising hopes for peace, only to be shattered without warning by sporadic gunfights along the foothills that reopen barely-healed wounds.

But even during these short spells of respite, the undercurrents of hostility remain unchanged. Civil bodies of the warring communities have imposed blockades and counterblockades, restricting or ending not only passenger traffic but also that of goods and commodities, making life miserable, especially for the poorer sections that cannot afford essentials at dearer prices. Given the underlying tensions, it only needs a small spark to light devastating flames.

All the while, what has also become apparent is that the state government is not only clueless but also not autonomous. The chief minister, N. Biren Singh, and his cabinet colleagues routinely rush to New Delhi for approval of every strategy, reinforcing the popular belief that the state government is no more than a puppet on a string. There was also the suggestive endorsement of the state government by none other than the Union home minister in Parliament during the August no-confidence motion against the Centre. When asked if a change of leadership or a spell of president’s rule was being contemplated in Manipur, his answer was in the negative, stating that the state government was cooperating with the Centre.

That aside, the question that remains unanswered is this: whatever be the administrative structure that the Central government prefers in the state, why is it not

bothered about the state government’s inability to size up the crisis and end it?

The Bharatiya Janata Party could be taking for granted the stereotype that electorates in northeastern states like Manipur always lean towards the party in power in Delhi.

The conflict has already taken an officially-confirmed toll of 175 people dead, 1,118 injured and 32 missing. Of the dead, 96 are still in state mortuaries, their bodies yet to be claimed. There have also been at least 5,172 cases of arson of which 4,786 have been homes, 254 churches, and 132 temples. Over 60,000 people are also estimated to have been displaced and are residing in community-run relief camps.

About 5,000 looted guns are also still in the hands of rioters, a bulk of them taken from police armouries in the valley areas. Arms lootings took place in the hills too. Indeed, the first robbery was from a licensed gun shop in Churchandpur opposite the main police station on May 3 that was captured on multiple CCTV cameras and the footage widely circulated on social media along with the images of arson attacks of the day. The first information report lodged by the shop-owner says 500 assorted weapons, including 17 pump-action repeater shotguns, were among the looted arms. The next few days witnessed a spree in gun-looting by mobs everywhere.

It is also confounding that total area domination has not been achieved by the government despite the concentration of around 60,000 Central forces which, together with the state police constabularies, would add up to nearly a lakh pair of boots on the ground. Other than fire-fighting operations when clashes break out, no visible effort is being seen to bring the situation under control. This is unfortunate; an end of open hostility has to precede any community-level reconciliation initiative.

Is there then a bigger plan? Is the conflict being allowed to drag on so as to

compel Meitei insurgents in their camps in Myanmar to return to join the fight in a big way so that they can be cornered and made to come to the negotiating table,

just as Naga and Kuki insurgents had been? If the wait is for such an outcome, the disturbing question is — what about the expected exponential increase in collateral damage?

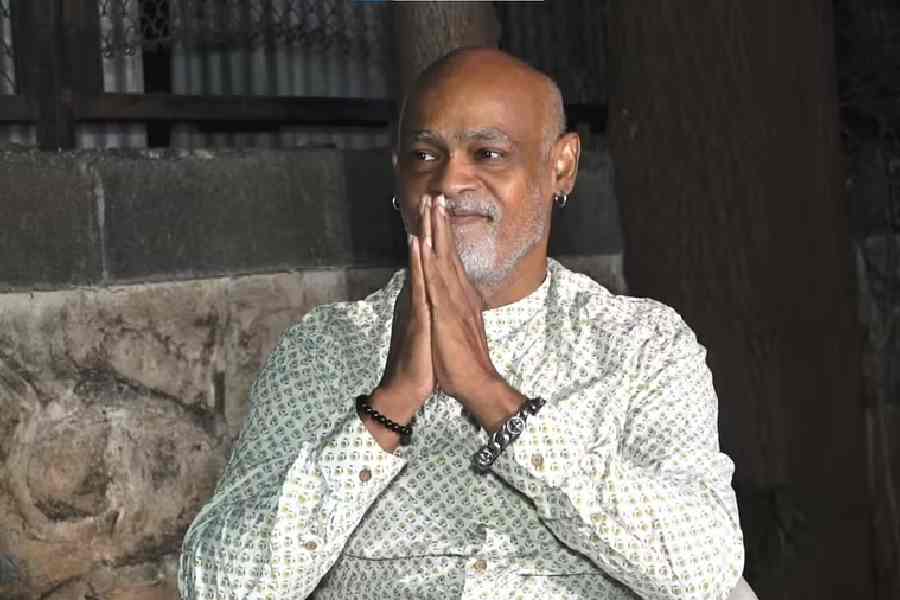

Pradip Phanjoubam is editor, Imphal Review of Arts and Politics