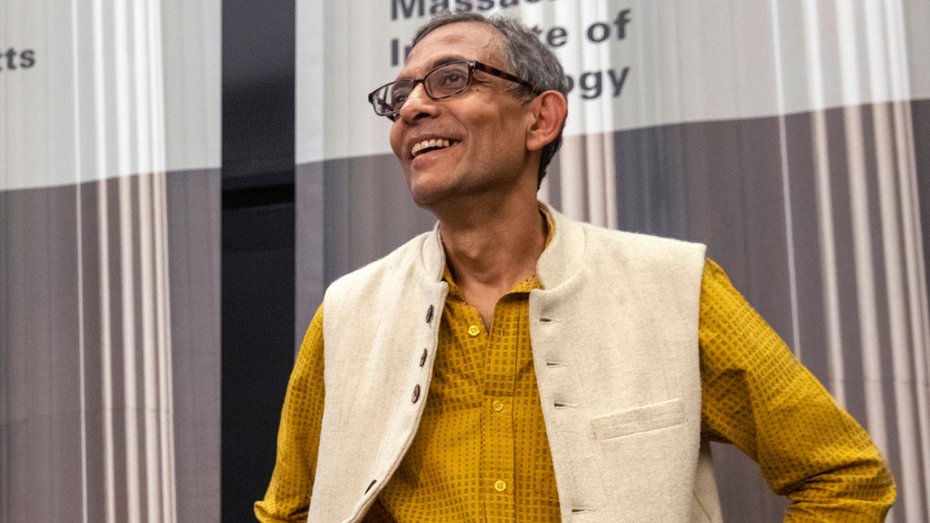

A remark made by the Nobel laureate, Abhijit Vinayak Banerjee, regarding the poor health of the banking sector in India is one among the many similar comments that have been made by economists in the recent past. The most worrying aspect of bank portfolios is the large proportion of non-performing assets, which constitute bad loans, especially in public sector banks. In this context, most pundits have pointed to the lack of adequate regulation that allows opportunistic behaviour to thrive. Public sector banks are also vulnerable to political interference in the choice of borrowers and the disbursement of loans. Mr Banerjee, however, indicated that there was actually an over-regulation of public sector banks that led to political pressures, as well as strict monitoring by Central vigilance authorities if something went wrong. The Central Vigilance Commission has set up, in consultation with the Reserve Bank of India, the Advisory Board for Banking Frauds, which will investigate all frauds in public sector banks above the amount of Rs 500 crore. Bankers, finding themselves caught between the government and the vigilance commission, would become extremely risk averse, while hoping that political interference would somehow be kept at bay. Therefore, bankers find concealing bad debts for fear of consequences to be to their advantage. A bank may be doing well when something suddenly goes wrong in a big way.

Mr Banerjee raises a second issue in this regard. Bank balance sheets are not picking up early warning signs about the deterioration in the quality of assets. Clearly, the inference is that a bank’s financial data may not be as transparent as they ought to be. Mr Banerjee has argued, therefore, for a reduction in the equity stakes of the government in public sector banks to a level below 50 per cent. This would reduce political control as well as the fear of the CVC’s investigations. Banks would be more prudential while still being able to take the usual business risks necessary for growth without undue fear. Banking decisions, like all business decisions, can be mala fide, or they can reflect poor judgment. For the borrowers, it is typically taken to be poor business judgment when they are unable to pay back the bank. For a banker, the opposite is usually assumed; the decision was ethically wrong and there is no scope of bad judgment in decision-making by seasoned bankers. This implicit assumption needs to be changed. The recommendation for equity reduction also converges with the standard efficiency-enhancing argument in favour of the privatization of public sector banks.