Last December, the Supreme Court had issued a notice on petitions seeking recognition of ‘same-sex marriage’ to transfer the pending cases before itself. The main petition seeks to challenge the Special Marriage Act, 1954 for discriminating against same-sex couples. Thus, the case also addresses privacy concerns surrounding the Act.

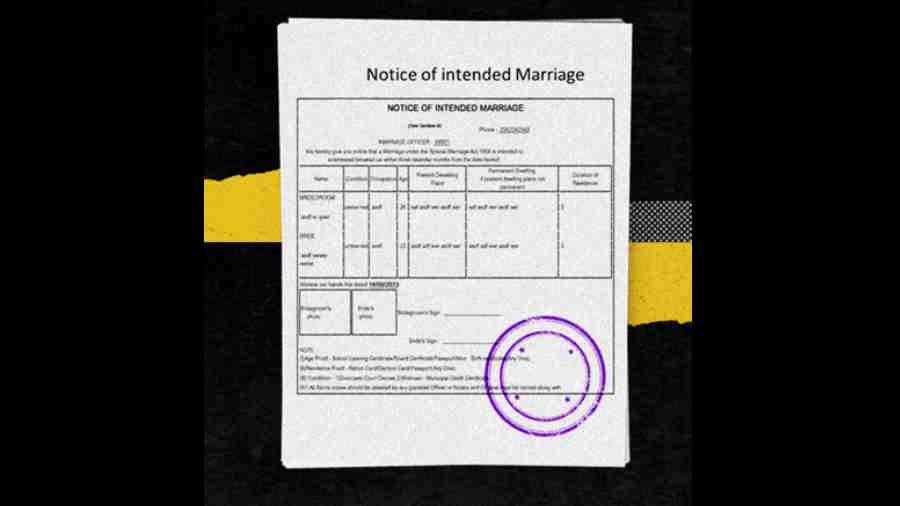

Section 6 of the SMA, 1954 provides that the marriage officer must publish an open notice before solemnising a marriage under the Act. The purpose of the notice is for objections to the marriage, as per any of the valid conditions of marriage enlisted under Section 4, to be conveyed to the marriage officer.

The open notice and invitation to objection affect the autonomy of the two persons who want to solemnise their union under the law. Many a time, couples elope to marry. These open notices put their privacy and safety in jeopardy as their location, address and names are listed on the notice. According to National Crime Records Bureau data, hate crimes have been on the rise in India. Given such a communalised atmosphere, when personal information of an inter-faith couple is published, it puts them in danger from their families and hatemongers.

The issue had come up before the Supreme Court in 2020 when a law student challenged the provisions of the Act that provided for open notice in a conspicuous place as illegal and violative of the right to privacy. The court did issue notice to the government but the case did not proceed further. But the Allahabad High Court took a leap forward in Safiya Sultana vs State of U.P. and observed that “The requirement of notice under the Act only arises when couple requests such notice to be published under Section 5 of the Act. Hence, there is no mandatory requirement of open notice under the Act.” The judgement by J. Vivek Chaudhary was applauded by the legal community for its progressive nature and beneficial interpretation. But a similar petition had been dismissed at the preliminary stage by the Supreme Court on the grounds that the party bringing the challenge was no longer an aggrieved party under the SMA, 1954.

The courts have not gone into the constitutionality of these provisions up until now. This has resulted in the perpetuation of anxiety among inter-faith couples to share their personal information in public. Incidentally, neither Islamic sharia law nor the Hindu Marriage Act has any such provision for registration of marriages.

The case before the Supreme Court is an opportunity to explore several important questions. An investigation of the constitutionality of these provisions may be an imperative, especially if the court decides to expand the scope of the SMA to include same-sex couples within its ambit. The LGBTQI community is more vulnerable to violence than any other minority.

The issues of privacy and safety must be deliberated upon while deciding this matter. The liberty of two individuals who want to solemnise their union should not be put in jeopardy by the invasion of their privacy as well as an impediment to their right to choose their partner.