As we approach the nation’s 78th Independence Day, I am thinking of the National Archives of India to which I travelled for the first time one spring morning of 1992 on the back seat of a young milkman’s bike. Edward Lutyens’ beige-and-brown neoclassical monument seems to have escaped, for now, the demolisher’s hammer. That comes as a relief because for nearly a century now, its vast corpus of records has provided sustenance to tens of thousands of scholars worldwide.

This corpus, of course, was not built in a day. Dipesh Chakrabarty’s book, The Calling of History: Sir Jadunath Sarkar and his Empire of Truth, recalls an age in the early-twentieth century when historians had to act as “hunters and gatherers of historical documents” — travelling far and wide, keeping an eye out for European officials auctioning off their libraries before leaving India, tracking instances of the pre-British local ruling elite putting their private records on sale, and constantly badgering the colonial administration for providing public access to official records in incredibly small increments. As late as 1937, scholars had to pay to the Keeper of the Imperial Records Department an ‘examination fee’ of Rs 2 per 10 typed pages (a minimum of Rs 15) merely to have their notes screened by officials. Microfilming of documents necessary for historical research was a hotly debated subject even in the 1940s when photocopiers were still a thing of the future.

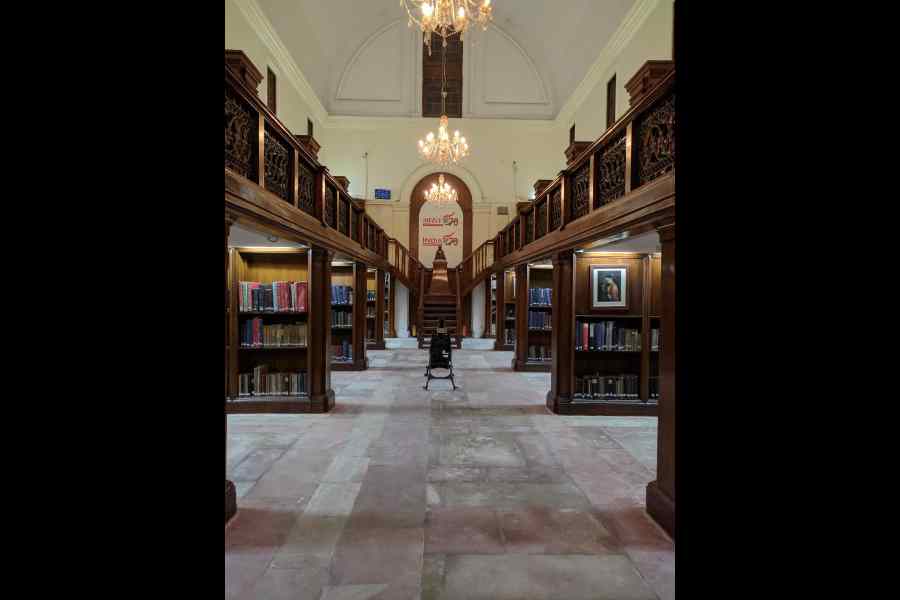

Standing on the shoulders of those giants who toiled tirelessly in little-known repositories of ‘primary sources’, we have made giant strides in the last two decades when the internet and online subscriptions have emerged as indispensable aids to research. From copying and taking notes from original sources by long hand, through typescripts and mimeos, microfilms and photocopying, to Google Books and the Internet Archive, we have traversed a very wide terrain. But ‘archives’ — in the sense of silent, sombre and forbidding places where frowning archivists dish out fragile documents only a small handful at atime — still dominate in a large chunk of the world. Scouringfor usable ‘primary sources’ insuch places is usually a very tactile experience, involving rustling up pages with extreme caution, theuse of lead pencils, and dirtying one’s fingers — all historians’ equivalents of digging in the trenchesof excavation by archaeologists.

Moreover, archives of primary sources are often like a large sea with navigational routes not clearly mapped out; one needs to cast one’s net wide and keep looking for the prize catch, the piece of yellowed paper that will clinch the argument, chart a new direction, trash the unsuspecting predecessor who had never located this ‘big fish’. There are no ‘keyword searches’ to fall back on in times of doubt. Days of toil with no immediate reward in sight — other than the delightful digressions and hidden alleyways that keep turning up every nowand then — are completely in tune with the ways of the archive. Master and apprentice alike, all researchers must walk them as valiantlyas they can.

Assigning too much importance to the archival needs of scholars, however, may obscure the criticality of the use of archives for teaching. The use of archival sources is central to the practice of history, with enormous potential for increased student engagement. Ideally, students should not only learn history but also ‘do’ history — actual research — as part of a participatory learning experience. This ‘doing’ empowers them by giving them a taste of what it is like to be real historians. Students can develop their critical thinking skills by using primary sources to assess other interpretations of history and create their own ones.

Yet, it’s surprisingly common in India for history students to receive even their Masters degrees without delving into primary sources. They don’t learn the skills of archival research and miss out on the satisfaction of making their own historical discoveries. By contrast, the undergraduate curriculum in history in many universities in the Western hemisphere, particularly in North America, puts significant emphasis on the use of primary sources. This is most visible in Honours programmes, which include ‘History Workshop’ or ‘History Lab’ courses that seek to train students to read and assess original sources and to write like a historian, analysing manuscripts, rare books, private papers and correspondence, newspapers, old printed literature and so on, thereby forming original interpretations and arguments.

Of course, direct access to the archives is not always possible, which is why handbooks exist, presenting carefully selected and collated transcripts of primary material for use by students (as well as scholars). The best ones to be commonly used include, for ancient and medieval India, Classical India, by the doyen of ‘world historians’, William H. McNeill, Nihar Ranjan Ray’s A Sourcebook of Indian Civilization, and the timeless classic, Sources of Indian Tradition, which has seen several reprints and new editions. For modern South Asia, one usually falls back on the second volume of the Sources, but other excellent options include Barbara Harlow and Mia Carter’s Archives of Empire, and John Marriott and Bhaskar Mukhopadhyay’s ambitious six-volume set of documents, Britain in India, 1765-1905. None of these volumes is without its problems, not least the personal preferences and idiosyncrasies of their editors. Moreover, these volumes contain transcripts of original texts, not facsimile images, so the sheer physicality of the original documents does not come through in them. Yet, their existence testifies to the critical importance of the need to integrate primary sources in the curriculum of South Asian history courses and, thus, to make the archives accessible to students and teachers, though at several removes.

Close to Independence Day, let me ponder two things. One, an example of how our syllabi could benefit from an exposure to primary sources. It turns out that although we read about a myriad scholarly interpretations of the ‘nature’ of 1857 at various levels of the history curriculum (a ‘Sepoy Mutiny’ or a Jang-e-Azadi?), our history students seldom read one of the revolt’s most critically important primary documents, a proclamation pledging a joint Hindu-Muslim collaboration towards freedom from British rule, written by Firuz Shah — one of emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar’s grandchildren — and promulgated from Azamgarh in Uttar Pradesh in May 1857. This ‘Azamgarh Proclamation’ appears only in one of the NCERT school textbooks as a ‘source’, though without any contextualising text. And, yet, it’s included along with a detailed editorial note in the Sources of Indian Tradition, the compendium of primary sources widely used in teaching South Asian history in various universities in the Euro-American world.

And now on to the second, an instance of erasure. As we prepare for another round of Independence Day celebrations from that twilight zone between laughter and forgetting, it behoves us to think of those very few that are still living, from among the millions that experienced, at first hand, that dark twin of our Independence, the Partition. These are our forgotten people who didn’t have pensions, and whose children have never had reservations. In a few years’ time, a once humongous, largely untapped, and now rapidly diminishing, archive of their stories of loss, displacement, and epic struggles to rebuild lives will be lost to us forever. Our nation will be better served by a project to recover and document these stories before they are gone, and not by decking up metro stations with rushed-up ‘Partition Horrors Remembrance Day’ exhibitions, as was done a couple of years ago. Let’s hope this essential kartavya doesn’t fall through the trapdoor of history amid the fanfare on Kartavya Path three days from now.

Jayanta Sengupta is Director; Alipore Museum; jsengupt@gmail.com