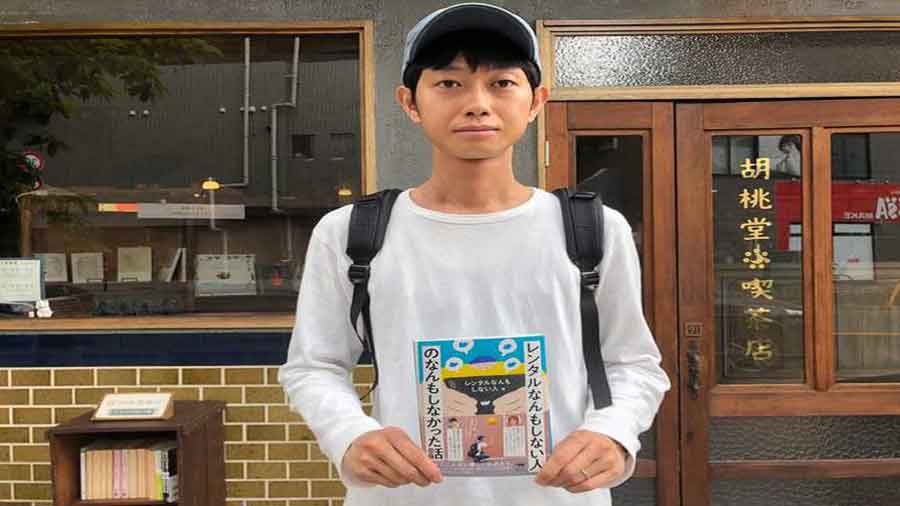

For most people, work is an endless list of tasks to finish, with lots to do and not enough time to do it all. But for one man in Japan, it is quite the opposite. In Tokyo, Shoji Morimoto has been offering himself ‘for rent’ since 2018 to ‘do nothing’. Yet, what seems like ‘nothing’ has him in such high demand that Mr Morimoto has accepted some 4,000 requests, including one client who has hired him 270 times, since starting his business. What, then, explains the man’s popularity? Mr Morimoto offers companionship— a priceless commodity in a world where two out of every five people have become lonelier since the pandemic. Mr Morimoto’s patrons require nothing more from him than his non-judgmental presence: he has watched a movie with one client, flown in a helicopter with another, heard a cheater confess to an affair over a meal, accompanied someone while submitting divorce papers, visited a hospital to stay with a patient who had attempted suicide and so on.

It may seem ironic that at a time when the world is more connected than ever before — 3.01 billion people keep in touch with one another via the internet — people are assailed by a sense of crushing loneliness. The era when being solitary was a cherished goal — Greta Garbo had famously quipped, “I want to be alone”— is now gone. Human contact is increasingly becoming a luxury good and the market appears to have realised that there can be a stiff premium on companionship. The start-up, Goodfellows, supported by Ratan Tata, aims to connect youngsters with senior citizens so that the latter can have company and the former jobs. There are applications that allow people to hire a ‘mother’, a ‘father’ or a ‘girlfriend’ for a day. There are even AI bots that try and replicate the human experience of a friendly chat. That so many are willing to pay for companionship, a fellowship that was assumed to be freely available in the not-so-distant past, speaks of the profound scale and depth of the modern phenomenon of loneliness. Estimates suggest that as much as 33per cent of the world’s adults consider themselves to be lonely. The disintegration of the extended family, coupled with technological advancements, may have aggravated the loneliness epidemic. Even though everything — work, leisure, recreation, company— can be ordered at the click of a mouse,the experience of organic bonding, the pleasure of in-person encounters,remains irreplaceable to the human mind. The pandemic, with its periodic lockdowns, has aggravated matters, as has the disappearance of greenery and spaces that facilitated the collective. A study found that adults in neighbourhoods where at least 30 per cent of nearby land was parks, reserves and woodlands had 26 per cent lower odds of becoming lonely compared to their peers in areas with less than 10 percent of green space. Ironically, loneliness is a shared phenomenon. This sense of sharedness must be tapped into in the battle to make life a bit more crowded.