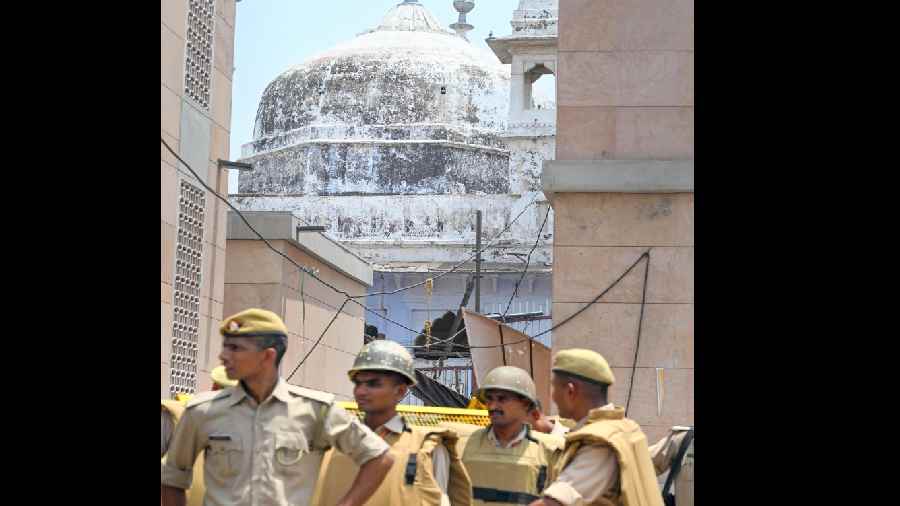

The Supreme Court’s decision to allow the cordoning off of a part of the Gyanvapi mosque ordered by a lower court in Varanasi illustrates the way in which the judicial process sometimes creates facts on the ground.

The original suit to allow Hindu worship in the Gyanvapi mosque should have been dismissed in the first place by the lower court. Section 4 of the Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act 1991 (henceforth PoW) bars filing any suit or initiating any other legal proceeding for a conversion of the religious character of any place of worship, as existing on August 15, 1947. Instead, the court limited Muslim worship in the mosque to twenty namazis till the matter of the ‘shivling’ was resolved. When the case was referred to the Supreme Court, it permitted normal Muslim worship unrestricted by numerical limits, except in the wuzu area where the fountain was claimed to be an ancient shivling. The court then referred the case to the lower court to decide upon the original suit.

The decision raises important issues.

One, the court could have ruled that Muslim worship would resume in all of the mosque, given that the PoW explicitly ruled out the conversion of the religious character of a place of worship. The cordoning off of the wuzu area is, de facto, a change in the religious character of the mosque.

Two, there had been several previous attempts to do an end run around the PoW, and these had all been struck down by the civil court and the Allahabad High Court on the basis of the PoW Act. As recently as September 2021, a lower court’s ruling that the Archaeological Survey of India ought to investigate whether the Gyanvapi mosque was built over an earlier Hindu temple was stayed by the Allahabad High Court. The high court even censured the Varanasi city court for its decision.

The obvious objection to the Supreme Court’s decision to partly suspend worship in an allegedly disputed area is this: even if, for the sake of argument, it is allowed that the wuzu fountain is a shivling, it still doesn’t change the fact that the PoW forbids the conversion of the religious character of any place of worship as it existed on August 15, 1947.

The PoW was explicitly meant to ensure that the argument about the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya being a Hindu temple would not be treated as a precedent for subsequent claims of this sort.

It’s not as if the Supreme Court is unaware of the purpose of the PoW. In its judgment on the Ayodhya title dispute, it cited the Act as a guarantee that the passion play of Ayodhya would not be enacted again on some other site. The bench leaned heavily on the Act to underline its view that its decision in favour of the Hindu litigants did not constitute a precedent. It’s useful to quote from that judgment to illustrate the bench’s endorsement for the PoW: “The State, has by enacting the law, enforced a constitutional commitment and operationalised its constitutional obligations to uphold the equality of all religions and secularism which is a part of the basic features of the Constitution. The Places of Worship Act imposes a non-derogable obligation towards enforcing our commitment to secularism under the Indian Constitution… Non-retrogression is a foundational feature of the fundamental constitutional principles of which secularism is a core component. The Places of Worship Act is thus a legislative intervention which preserves non-retrogression as an essential feature of our secular values."

And again: “The Places of Worship Act which was enacted in 1991 by Parliament protects and secures the fundamental values of the Constitution. The Preamble underlines the need to protect the liberty of thought, expression, belief, faith and worship.”

Justice D.Y. Chandrachud, as a member of the bench that decided the title suit, was a party to this judgment. It’s reasonable to assume that he co-authored the passages cited above. This raises a question. Having shown us how important the PoW act was to fundamental constitutional principles, why did he not dismiss the suit as the Allahabad High Court had done before with a similar suit, on the grounds that it wasn’t permitted by the PoW?

The one clue we have to his thinking is not contained in the Supreme Court’s order but in an observation made by him: “... the ascertainment of a religious character of a place, as a processual instrument, may not necessarily fall foul of the provisions of Sections 3 and 4 (of the Act).” In a possible reference to the claim that a shivling had been found on the Gyanvapi Masjid’s site, Justice Chandrachud observed that religiously hybrid sites are not unknown in India. The example he chose was the hypothetical presence of a cross in an agiari, a Parsi place of worship, and he went on to suggest that the PoW would ‘apply’ to the cross. But the PoW could not apply to the cross, if on August 15, 1947, the agiari was established as a Parsi place of worship. Obiter dicta often have an enigmatic, cryptic quality to them, but it’s hard to see how the PoW applies to Justice Chandrachud’s hypothetical example. It is concerning that he seems to think it does.

It’s reasonable for the Supreme Court to return a case to a lower court while interim arguments are being made because no apex courts wants to risk a final order that cannot be appealed without all the arguments being heard. If this was Justice Chandrachud’s concern, it seems reasonable to argue that the state of worship in the mosque should have reverted to the status quo before the suit was lodged. The default position ought to be that the PoW applies to every place of worship till a court decides that it doesn’t. The ‘ascertainment of the religious character of a place’ is not a function of disinterested historical curiosity, but a means to an end. Over the last three decades, we have seen court-ordered surveys weaponized by cruising kar sevaks; it was this religious revanchism that the PoW explicitly set out to forestall.

The Supreme Court has a special responsibility in this matter given its history. In 1994, a bench headed up by Justice J.S. Verma ruled that “A mosque is not an essential part of the practice of the religion of Islam and namaz (prayer) by Muslims can be offered anywhere even in open.” This judgment, which took it upon itself to rule that congregational prayer is not essential to a congregational faith, weakened the fundamental right of Muslims to practise their faith freely. In the majoritarian context of contemporary India, the superior courts, having resoundingly endorsed the PoW in the Ayodhya judgment, should rule consistently against all suits that violate the principle of ‘non-retrogression’. What the republican order requires from the courts in this matter is clarity, not Talmudic nuance.

If majoritarian politicians want to subvert the very principle of the PoW, they can pass a law superseding it. The National Democratic Alliance has a large majority in Parliament and such a law is wholly within its power. It would be a catastrophic move but it would have the merit of making the ruling dispensation’s prejudices explicit. The worst of all possible worlds would be one in which the Act, celebrated by the Supreme Court as a law that “... secures the fundamental values of the Constitution” is husked, unwittingly, by the mills of justice.

mukulkesavan@hotmail.com