I want to begin with an old story. Years ago, I went happily to watch a film on Winston Churchill. I was impressed and came back and told my father excitedly that Churchill was a hero. My father smiled and said quietly, “He was not fit to touch Gandhi’s shoes.” Even as a child, I realized it was not a mere nationalist statement. My father explained that a man who could walk away from the Bengal famine was no hero. Heroism was about caring, a sense of courage with responsibility. He then added, “Peace is a form of heroism. It requires the courage of action and thought. Bully boys like Churchill do not fit the role.”

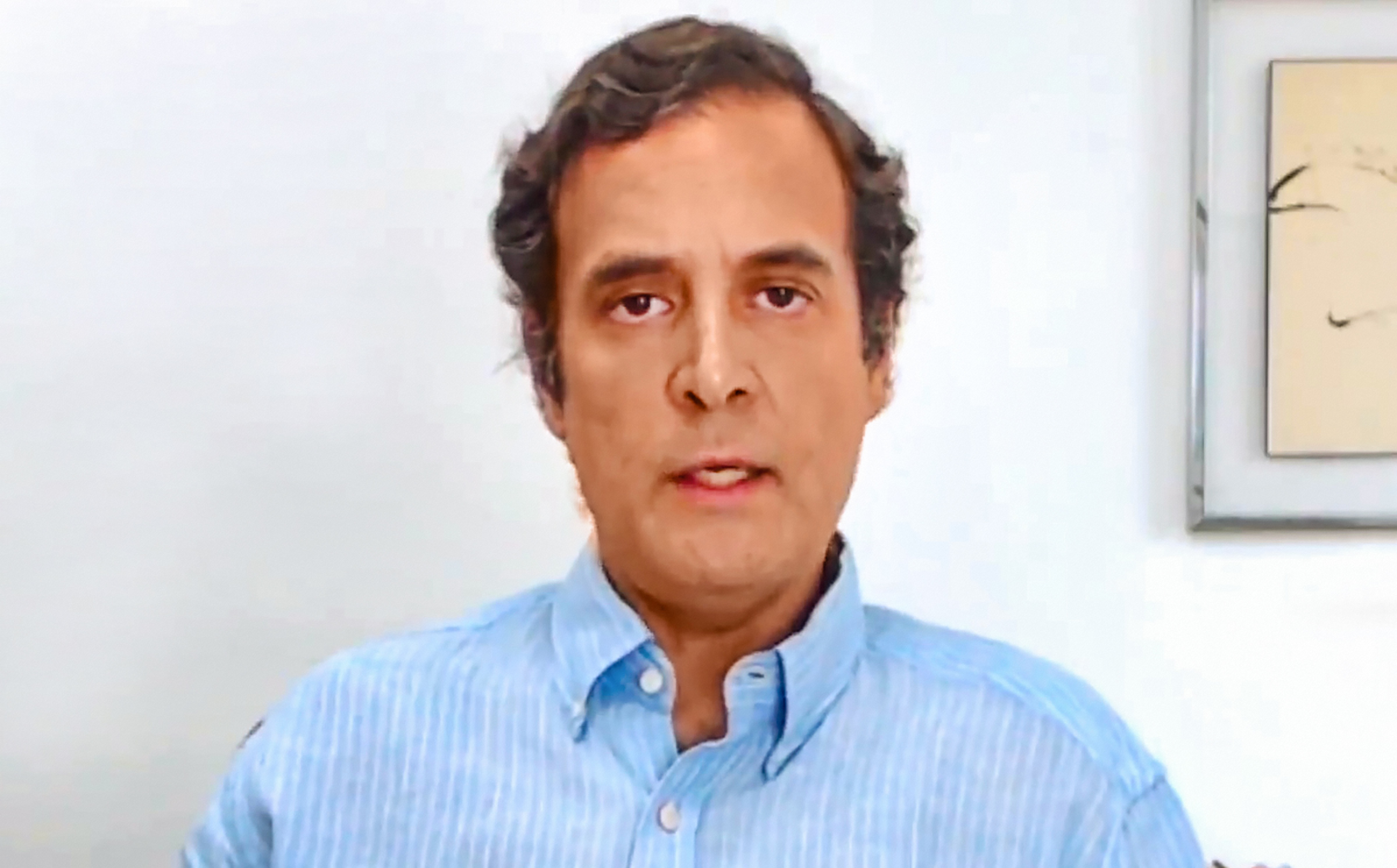

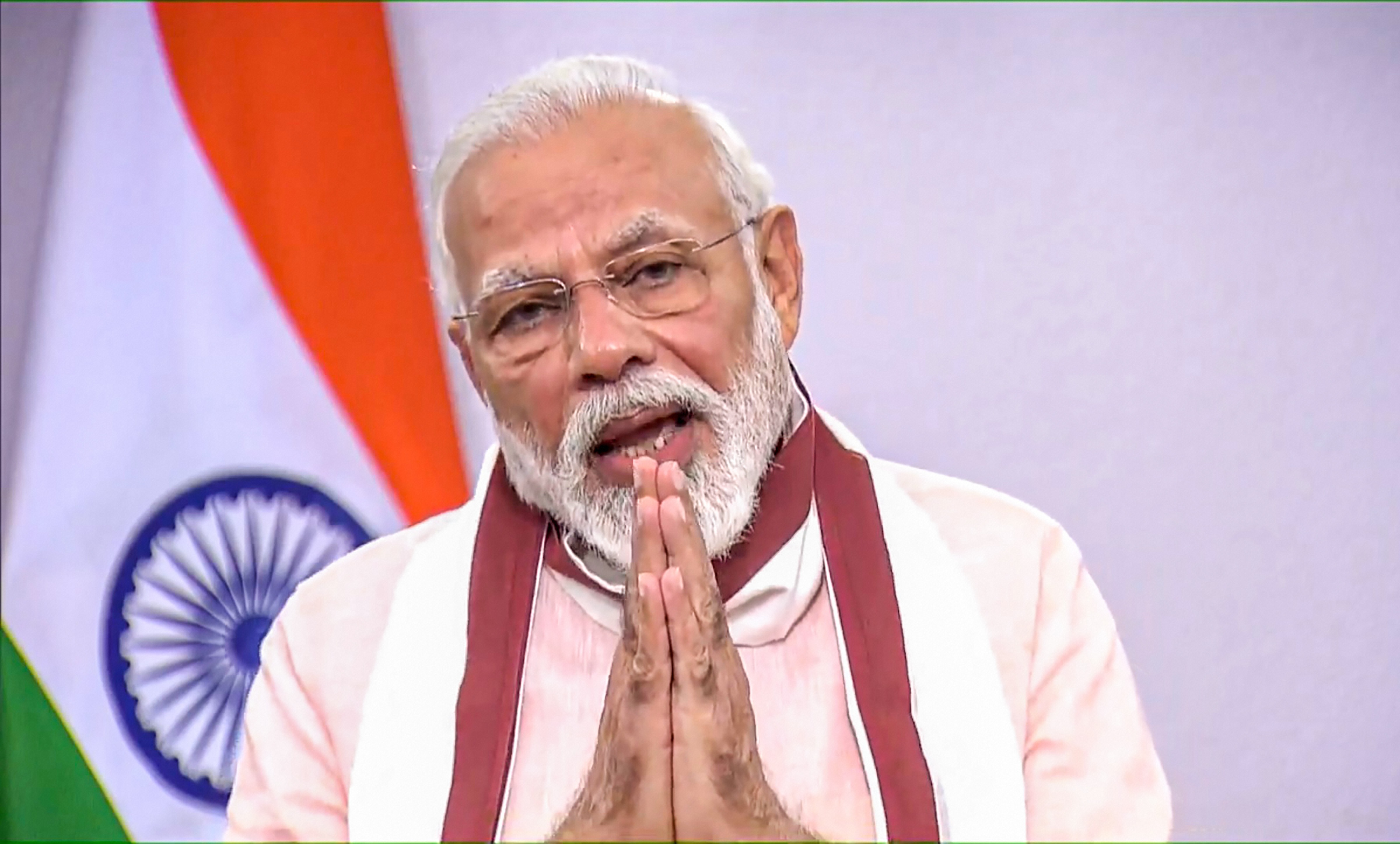

The story stayed with me. When the first reports of the Chinese incursion at Galwan came, I was disappointed with the way we responded. It was as if the Chinese were another virus. Narendra Modi and Rajnath Singh sounded like bid players mouthing lines they had been hurriedly fed. Even the Opposition, desperate for brownie points before election time, was equally facile. Rahul Gandhi in calling Modi ‘Surrender Modi’ sounded glib and superficial.

There was no sense of commitment to solidarity, a sense of a nation rethinking and working through the implications of war. As an observer put it, “the sages were missing.” But as days went by, the absence was conveying a deeper crisis.

We seem to be a nation of politicians who refuse to be statesmen. Beyond the absence of leadership, one felt an amnesia about the past, one missed the Gandhian imagination, the courage of Badshah Khan. There was no appeal to reason or peace, just a badly-scripted jingoism spouting patriotism and a security discourse out of a badly-scripted policy document.

No one got up and said the last thing we want is war, and the first thing we need to think through is peace. The political confidence of India being a civilization and a democracy was missing. To talk peace requires confidence and courage, which go beyond the current scripts of an arrogant nation-state.

The Indian thought on war has been derivative. One sees little mention of Gandhi or the Pugwash movement. But these are two traditions that we must revive. It is true that Pugwash was focused on the anti-nuclear movement, but it always hinted at a wider search for peace. One needs a sense of Pugwash and science on war today. Our scientists have become an army of clerks, not philosophers breathing alternative worlds and utopian imaginations. Sadly, even the Gandhian imagination was made for export. The great Gandhians after the 1960s were foreigners like Martin Luther King, Albert Lutuli, Desmond Tutu, Steve Biko, Václav Havel and Lanza del Vasto. The Gandhian idea no longer exhibits a trusteeship of peace as a way of life, or a renewed pursuit of new experiments with truth. It is not in development that India lags behind, but in its experiments in peace.

This need to think of the immediacy of peace at the national level merges with the urgency of confronting the Anthropocene. The question of man’s violence to nature and his violation of the earth has gone beyond limits. Peace today begins as a planetary peace, a way of going beyond the Judeo-Christian use of nature as an economic resource, a way of going beyond the capitalist sense of nature. Peace needs a new reworking of science and a rethinking of economics. In fact, India must constitutionalize nature by representing forms of life — rivers, lakes, swamps, the forest and the sea — as constitutional entities. One is not merely giving them rights, but endowing them with the ecolocy of trusteeship. We have to realize that nature in the long run does not need us; we need nature. In an evolutionary sense, nature can shut us off as a temporary intrusion. The works of scientists like James Lovelock, Lynn Margulis and Isabelle Stengers have to be seen as an invitation to peace. Ecology has to be a part of the holism of peace. Gandhi’s idea of the Oceanic Circles, which saw the spiralling of life from a dew drop to an ocean, is an anticipation of this.

If peace is planetary, it is also vernacular, and Gandhi’s ideas of swadeshi and swaraj encompass both. Gandhi needs to be rescued from the mediocrity of the current regime, which has little sense of the local or the vernacular. Gandhi’s swadeshi was an attempt to save the locality as a life form, as forms of livelihood. It included local crafts, local languages, local species, and local cosmologies. For a Gandhian, saving a language, a craft, or even a life form, or even a hint of colour was as much a part of the craft of peace as the formal act of dissenting against war. Swadeshi was a tribute to diversity, while swaraj captured a sense of the wholeness of the universe. A Gandhian notion of peace could save a craft, a language, and yet combat genocide and extinction. The satyagrahi as an exemplar, as common man, as scientist, is a central figure in swadeshi and swaraj, seeking a loom of peace to create a web of non-violence.

Peace requires dialogues and a dialogic culture at three levels. We need a dialogue of civilization and religions: here India must rethink the dialogue of Islam and Hinduism to create new myth of peace. We need a dialogue of disciplines to create a more holistic knowledge system. Thirdly, we need a dialogue of vernaculars, which can be a dialogue of social movements. Peace then becomes an ethical search rather than a political act, where individuals and communities seek to minimize the violence of the State and other systems. For all its theoretical power, peace needs exemplars who can invent answers on their feet. For example, can we use Badshah Khan’s Khudai Khidmatgar as panchayats of peace on the border?

Indian democracy needs a new set of experiments to redefine itself. Our notions of the nation-state, development, security and majoritarianism have been emptied out, signalling the violence of vacuity. Democracy needs to engage with knowledge and violence to work out new possibilities. The social movements — Narmada Bachao Andolan, the Kerala fishing struggle, Chipko, Bhopal, the RTI movement — they’ve all attempted to reinvent nature, rethink technology and information. One must borrow from the embeddedness and memory of each to see how these insightful parts can move to the peace movement as a whole. We need to interrogate an Indian Pugwash movement, not just about particulars of nuclear energy but also to look at nuclearism as a form of violence. We need to explore the episteme of science, nudging Pugwash towards a wider view of peace and the Anthropocene. Pugwash was too often a drawing room exhibit in the salons of science.

Democracy needs storytelling and memory, stories of exemplars to inspire students. Peace has to have a touch of the literary, conveying both the courage of everydayness and of epic crisis. Peace has to convey a new ontology of everydayness, where women don’t wait endlessly for their husbands, where torture is remote and when communities create their own vernaculars of peace. Sadly, war is destroying the sense of childhood in many societies, and that is unforgivable. Peace is a way of guaranteeing the child the everydayness of justice. If poetry, as Robert Frost said, was a lover’s quarrel with the world, then peace is the housewife’s challenge in the political world at large. It’s time India and South Asia, as a dialogic region, create a new notion of the Russell-Einstein Manifesto. Democracy is desperate for the everydayness of peace. A civil society embedded in civilization with a sense of an inventive Constitution has to think of a new peace beyond the aridness of the current concepts of war and international relations. Every man has to invent his own version of Gandhi or Badshah Khan, Havel or Tutu, Lanza del Vasto or Albert Lutuli. Indian democracy has to come alive and be inventive around the dream of peace.

The author is an academic associated with Compost Heap, a network pursuing alternative imaginations