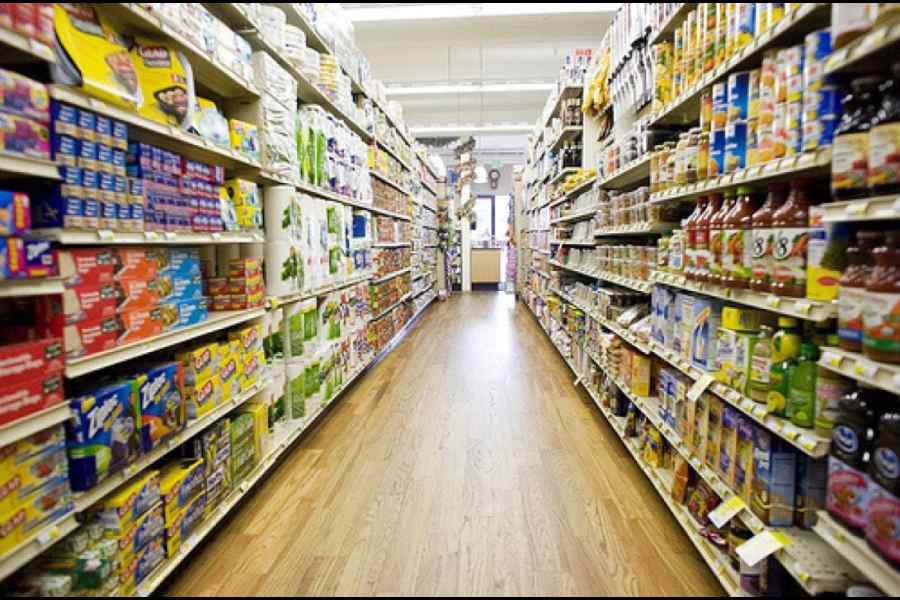

Some of India’s biggest business organisations have recently expressed concern at signs that a large section of consumers is not spending at a rate warranted by the nation’s impressive macroeconomic growth rate. The muted spending by the middle class has been mostly observed in the fast-moving consumer goods segment. The sale of two-wheelers and bicycles, for instance, has remained tepid. The reason being buyers of such products have been increasingly feeling the pinch of economic challenges arising on account of stubborn inflation and stagnant earnings. Consequently, a large segment of the domestic market of FMCG companies has not been growing. On the other hand, spending by the rich on expensive consumer goods, including imported ones, continues to be robust. At the other end of the income spectrum, subsidies and welfare transfers have improved the spending power of people who earn below five lakh rupees annually. However, the rise in average income in this group of income earners has not been enough to trigger a positive impact on the FMCG sector. Taken together, the trends indicate growing economic inequality among the rich and the poor, with shrinking purchasing power for the middle class.

These trends have tangible economic consequences. Given the weakening demand for FMCG and cheaper durable goods, companies are wary about investing in additional capacity. Hence, the rate of physical capital accumulation is decelerating. The burgeoning market for luxury goods that are mainly imported could be a signal for domestic production to begin in these areas. But that would be time-consuming and uncertain. An allied development on this front is the trend in which companies are indulging in larger doses of financial investments rather than in plant and machinery. Any shock to uncertain global financial markets would erode a large part of this invested wealth. Another implication of this trend of rising inequality is the likelihood of people earning an income below five lakh rupees prioritising spending on food. This, in turn, could lead to a further rise in food price inflation. The middle class may also shift from buying processed food to products to be cooked in the kitchen. These two developments together would lead to a macroeconomic situation of low capital accumulation and persistent food price inflation. The Reserve Bank of India would keep interest rates high, leading to a secondary round of muted credit off-take. Growth rates would be high with a flourishing secondary market in financial assets. But the central core of the economy could gradually become hollow.