On April 1, the chief ministers of Kerala and Tamil Nadu will jointly launch the centenary celebrations of the legendary Vaikom Satyagraha, the first prominent agitation in the country waged against untouchability under the national movement. The 20-month-long struggle held in Vaikom, a small lakeside town in the erstwhile Thiruvithamkoor (Travancore) princely state, began on March 30, 1924 and was against the ban on the backward castes from walking on the roads surrounding the famed Shiva temple.

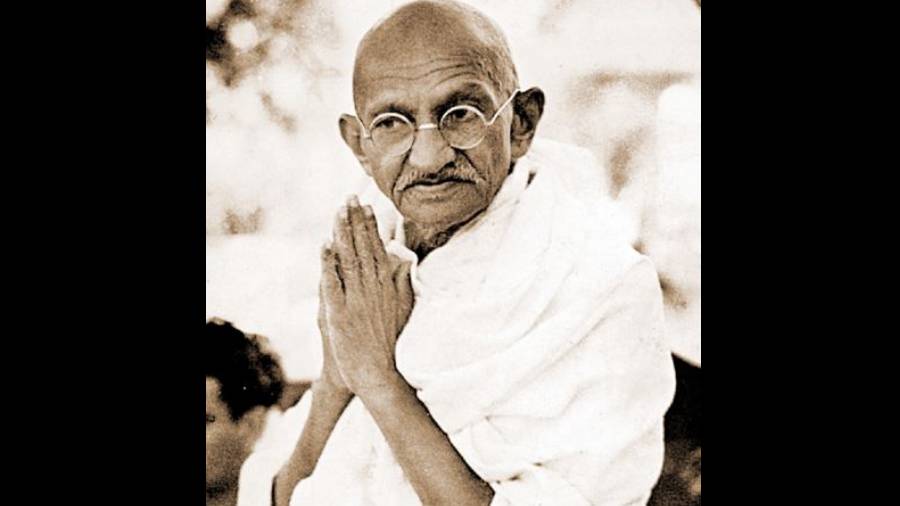

The struggle revealed that despite Thiruvithamkoor’s claim as a model state with the highest levels of literacy and health among India’s princely and British-ruled states, it had the worst forms of untouchability, which included even ‘unapproachability’ and ‘unseeability’. The backward castes were barred from temples and the roads around them. The Vaikom Satyagraha was directly led by an array of prominent political and social personalities of the day, including Mahatma Gandhi, Kerala’s sage-reformer, Sree Narayana Guru, Tamil Nadu’s rationalist, anti-caste leader, E.V. Ramaswami Naicker, and the Akalis from Punjab. It was a rare occasion when progressives from several Hindu upper and lower castes, Muslims and Christians fought together for the rights of backward castes.

Hundreds of men and women partook in the non-violent agitation that lasted for 604 days and braved prohibitory orders, arrests, physical assaults by the police and the orthodoxy, and even the century’s most devastating floods. The satyagraha ended with the Thiruvithamkoor government opening three of the four roads around the temple for all. A decade later, all the temples were also thrown open for everyone. Gandhi described the Vaikom Satyagraha as a “battle of no less consequence than that of Swaraj.” B.R. Ambedkar mentioned it as “the most important event in the country for the untouchables.”

Yet, was the Vaikom Satyagraha a great success as is held traditionally? Many contemporary historians think otherwise. They have challenged the idealised narratives describing the struggle as an unqualified success. According to them, the agitation’s achievements were limited. By getting reduced to an internal issue of Hindus, it ended up as a missed opportunity to awaken and mobilise the backward castes for a larger political and social movement. Interestingly, these revisionist historians blame Gandhi for the agitation’s failures much as they credit him for its achievements. Mary Elizabeth King, the American political scientist and civil rights activist, writes: “Gandhi’s involvement in Vykom had produced a compromise accepted by Travancore’s princely state government in relation to the Hindu orthodoxy; nonetheless, no concrete material gains were achieved for the untouchables.” (Gandhian Nonviolent Struggle and Untouchability in South India.) King told this writer that Gandhi’s insistence on converting the Brahmins’ minds to realise and atone for their sins through the nonviolent self-suffering of the satyagrahis led to the agitation’s failures.

EVR, who came to Vaikom from Tamil Nadu’s Erode with his wife, Nagammai, invigorated the struggle and courted arrest. Named ‘Vaikom Veeran’ (Vaikom hero), EVR dubbed the Gandhian compromise as the ‘Vaikom betrayal’. He resigned from the Congress immediately afterwards. The historian, T.K. Ravindran, wrote, “After twenty months of the relentless fight, Congress withdrew from the scene with its finery torn, and the prestige tarnished, leaving the cause of the depressed classes at the same spot whence they picked it up in March 1924.”

The Vaikom struggle’s most conspicuous failure was that the path used by the temple’s brahmin priests remained barred for the ‘polluting’ castes as part of the settlement. According to many, Gandhi’s insistence on a hasty settlement against the satyagrahis’ opinion and his restrictive stipulations led to this compromise. He barred volunteers from crossing police barricades or entering the forbidden roads. He insisted that the struggle not turn anti-Hindu or antagonise the brahmins or the royalty.

This was despite Gandhi’s failed discussions with the then government and the local brahmin chief, Indamthuruthil Nambiathiri, at Vaikom. Gandhi visited Nambiathiri at his home adjacent to the temple on March 10, 1925, a year after the agitation with his son, Ramdas, C. Rajagopalachari, and Mahadev Desai. During the three-hour-long discussion, Gandhi challenged the brahmin to prove that Hindu scriptures justified untouchability. Gandhi himself tasted caste discrimination from the brahmin. He was kept standing inside the doorway for much of the meeting while Nambiathiri sat at the farthest distance. Interestingly, the brahmin’s residence is now the office of the Communist Party of India’s Ezhava-dominated toddy tappers’ union.

Gandhi’s most controversial step was to keep out non-Hindus from the agitation, saying it was an internal issue of the Hindus. He even directed his close associate, George Joseph, Young India’s editor, not to participate in the satyagraha. Joseph, a Christian from Kerala, was in the agitation’s leadership and was arrested. Gandhi wrote to him, “I think you should let the Hindus do the work. It is they who have to purify themselves. You can help by your sympathy and by your pen, but not by organizing the movement and certainly not by offering satyagraha.” Gandhi also sent the Akalis back to Punjab after they came to Vaikom and opened a kitchen for the volunteers. Gandhi’s intention was to prevent the agitation from being branded anti-Hindu. King says that Gandhi wanted to reclaim the untouchables not solely for Hinduism but for the larger project of rejuvenating Hindu cultural nationalism.

Gandhi also kept the backward castes — the victims who initiated the movement — on the margins. He wanted the savarnas to be at the forefront to convert the savarna orthodoxy and prevent a confrontation within Hinduism. On March 12, Gandhi met the Maharani regent of Thiruvithamkoor and, later, Narayana Guru at his ashram in Varkala. Although Gandhi later wrote highly of Guru, their meeting witnessed several differences between them on caste and even on the efficacy of non-violence in fighting social disabilities. After his initial participation, Narayana Guru became less visible at Vaikom. Ayyankali, the period’s most prominent Dalit leader, also showed no interest.

According to King, Vaikom was a watershed that made the elimination of untouchability and the issue of temple entry a national concern for the first time. Without Gandhi’s patronage, it would have “diminished to a merely local, if not unheard of, event.” It led to the end of untouchability “as a source of acute misery in ... Kerala more than a decade before it was constitutionally ended by free India.” Yet, Gandhi’s “inexplicable and idiosyncratic” attributes prevented the religious-social issue from growing into a broader political mobilisation of lower castes.

Even as the centenary celebrations of the struggle for backward castes’ access to roads are on, Kerala’s famous shrine at Sabarimala remains barred for women of menstrual age in the name of tradition.