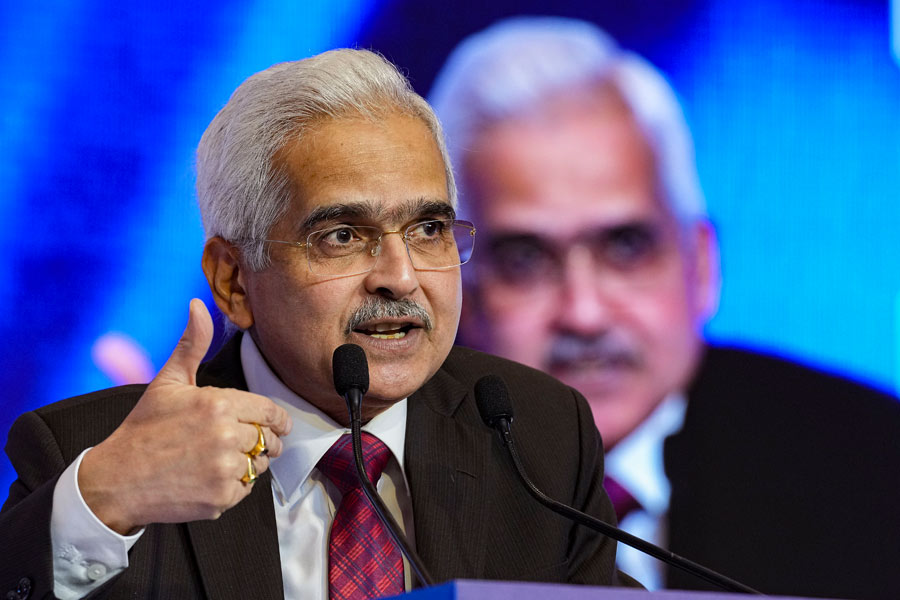

The comforting pea soup of asset quality numbers that stilled concerns about the health of the banking industry in recent years may be about to lift and reveal the gnarled roots of distress all over again. A sense of complacence had started to grow that the Indian banking industry had been finally able to exorcise the demons of bad loans. Data from the Reserve Bank of India reveal that gross non-performing assets of scheduled commercial banks had shrunk dramatically to 4.47% in December 2022 from a high of 11.46% in March 2018. In the case of private sector banks, matters had never looked better: net NPAs had slumped to 0.66% in December 2022 — less than half of the 1.97% in March 2018. But a sense of alarm spread through the financial sector when the RBI governor, Shaktikanta Das, warned recently that there are signs that the banks are resorting to the pernicious practice of ‘ever-greening’ loans. This is a practice where banks grant more loans to a borrower who is on the verge of default to help him pay back old loans and kick the can of repayments further down the road.

Mr Das’s diatribe against the sharp practices in the banking sector also raises concerns about how banks are becoming complicit in this parlour game of deceit. The good banks are helping out their troubled rivals by agreeing to buy the stack of bad loans at a discount and parcelling them out as derivative debt instruments. Good borrowers are also being persuaded to enter into structured deals with imminent defaulters to hide their stress; and, finally, banks are using internal or office accounts to adjust borrowers’ repayment obligations. Mr Das has not revealed how deep this problem really is. But there are clear signs of a throwback to the period when banks used artful devices to sweep the bad loan problem under the carpet. The worry is that it could explode into a crisis. There have been lingering concerns about how banks were forced to extend loan moratoriums immediately after the pandemic-induced lockdown and then chose not to recognise the stressed assets when the six-month period ended. Borrowers were given the option of restructuring these loans by at least another two years. There is a dark side to such reckless generosity: banks could end up with scarlet blotches on their books.