As a child and later as a graduate student in history, I have always been interested in that part of Calcutta that was never Bengali to begin with. In doing so, I endeavour to decentralise Calcutta from a predominantly Bengali ethnic point of view and show how this city was made and remade by migrant populations who were laborious, entrepreneurial, and subversive to structures that excluded them. Among the many migrant communities that gave meaning to this city, the Chinese were the ones who provided a lot in terms of tangible wealth and intangible culture. They were characterised by the anthropologist, Ellen Oxfeld, as “pariah capitalist”, a group that had economic capital but remained politically powerless. Among the Chinese migrant population that first settled in Achipur (present day Budge Budge) and later made their way to Calcutta, the Hupeh dentists were the last wave in the diaspora and probably the most surveilled.

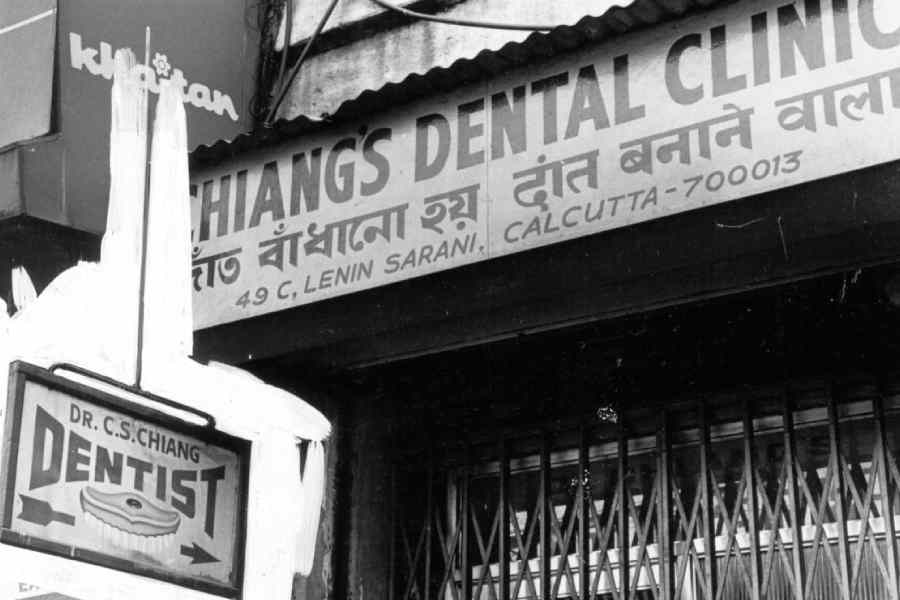

Hubei is a central province in China whose capital is Wuhan. During the 1930s, it witnessed a significant section of its population moving out to other places on account of the Sino-Japanese War. Due to Hubei’s spatial proximity to Calcutta as well as the provision of both an overland trail through Burma as well as a marine route through Southeast Asia, Calcutta witnessed a significant influx of Hubei dentists who set up practices all over the city. However, the most interesting aspect of this branch of therapeutics was that it gained popularity as an alternative to 20th-century colonial biomedicine and its concepts of ‘body’, ‘disease’ and ‘cure’. The keen-eyed city wanderer today will still find quite a few distinct residual structures on the streets of Calcutta. In the 1940s, there were around 80 dental clinics in and around Calcutta out of which 10 still remain in Tiretta Bazaar, Bhowanipore and Kidderpore.

Dr Mao Chi Wei’s clinic can still be found on Chittaranjan Avenue. When I stumbled upon his clinic for the first time, the thing that came to my notice was the architecture of the place and what it was trying to communicate to its patrons. In the clinic’s entrance as well as the seating area, one can still notice a flag of the Indian State peeking amidst an elaborate collection of Chinese proverbs and deities. This deliberate negotiation of national identity and efforts to pass off as ‘Indian’ and, thereby, ‘authentic’ can be found in a number of buildings and eateries all over Old Chinatown. Famously, the Sea Ip Church is known for keeping a picture of M.K. Gandhi right next to Sun Yat-sen in its central socialising space.

During my interview, I saw Dr Mao, now in his early 70s, setting a denture on one of his patients whilst casually chatting with him and cracking inside jokes. His practice is frequented by patrons from a diverse range of social backgrounds. In my little time as a guest in his clinic, I witnessed him deftly attending to both Hindu as well as Muslim working, lower-middle-class patients. His assistant, who herself is a woman from the local Muslim community in Tiretta Bazaar, is very well-versed in the doctor’s way and was keeping track of what I was writing whilst being vigilant about the line of patients waiting outside.

Dr Mao started off by telling me that of all the coastal provinces, the Hupeh dentists were the last to enter India. They came sometime between the end of the First World War and the beginning of the Second World War. They had picked up their dentistry skills on the elaborate shipping route they took to come to India which involved shipping out from Hubei to Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and Burma before entering West Bengal. Dr Mao said that when the Hupeh migrants left China, they only knew how to pick tooth worms and do topical treatment of infected teeth. Other, more sophisticated, skills of simple extraction and denture-making were picked up from Southeast Asia. The first migrants passed their knowledge and skills to the next generations. It is only in the last 50 years that the present generation started attending dental schools and getting BDS degrees, learning the modern technologies and gradually upgrading the profession. This was a direct outcome of the amendments made to The Dentists Act in 1948 when dental clinics needed approval from either the health department or a hospital having a dedicated dentistry wing. Before this, however, the practice of dentistry among Chinese settlers from Hubei developed without any regulation in a caste-like manner whereby it was almost as if the son or the daughter of a dentist had to be a dentist like his/her parents. On asking Dr Mao about this peculiarity, he replied, “I am privileged that way, it was easier for me. I can blend in the practices of the old world with the technology of the new world.”

The practice of Chinese dentistry, when analysed historically, appears to be a hybrid category by itself. It was neither originally aligned to Western biomedicine nor did it develop along the lines of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Dr Mao categorically denied Chinese dentistry being influenced by TCM as the practice developed primarily outside China. It, however, shares quite a lot of resemblance to the categories of ‘subaltern therapeutics’, the branch of medical practices and tools that developed in resistance to or in subversion of the State, to cater to marginalised communities that were chronically excluded from State-backed medicinal regimes.

The early Chinese dental clinics of Calcutta, run by practitioners and not degree-holders, dispensed affordable and effective treatment to members of Indian as well as Chinese-origin communities. They did not remain restricted to Calcutta to dispense treatment to an urban patronage. As per the Intelligence Bureau files housed at the West Bengal State Archives, Chinese dentists were mobile with their practices and went all around the districts of West Bengal, including Hooghly, Nadia, Birbhum and Darjeeling among other places. However, the statist intervention in the form of The Dentist Act co-opted this seemingly autonomous branch of subaltern therapeutics within the biomedical fold.

The current generation of Chinese dentists are all trained professionals practising abroad but the roots of their profession help us think about treatment and cure beyond codified and legitimised biomedicine.

Rishav Chatterjee is a graduate student of History at the University of Oregon