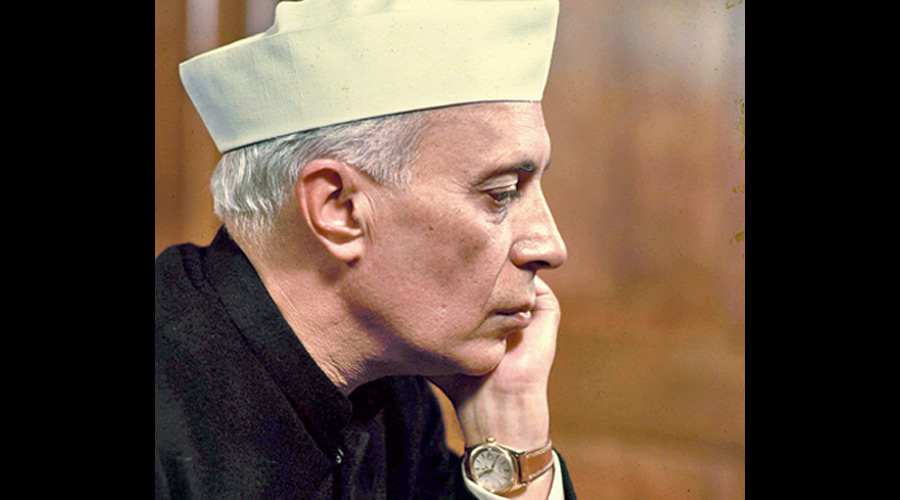

Jawaharlal Nehru was the architect of modern India. He took over India’sreins at the time of Mahatma Gandhi’s murder, the bloody Partition of India, and when India had been left devastated by colonial rule. Nehru strove to build modern democratic institutions, a secular State, and a pluralist nation. He also crafted public sector enterprises, inaugurated India’sspace programme, encouraged fellow citizens to adopt a scientific temperament, and laid emphasis on technical education and skill development through the establishment of the IITs and the IIMs.

Yet, Nehru is being lampooned in the 75th year of Independence. There is a full-fledged effort to malign his legacy. Ill-informed critics paint Nehru as someone who had a doctrinaire belief in socialism. Nothing can be further from the truth. I focus on a specific economic policy of Nehru to prove that his approach to economics was rooted in nationalism and pragmatism and not in some ‘red book’.

At the time of Independence, the temptation to use the newly-acquired political freedom to usurp foreign investment was high. This manifested in the form of hostility towards foreign investment. There was a wave of nationalisation of foreign investment sweeping through the world. ButNehru understood the significance of foreign investment in a country starved of capital. On April 6, 1949, Nehrulaid down the foreign investment policy statement in the Constituent Assembly that noted that his government would encourage new foreign capital on mutually advantageous terms. He promised ‘national treatment’ to foreign investors, assuring them that no restrictions would be imposed on remitting profits and dividends. Further, the statement noted that although majority ownership by Indians was preferred, foreign capital having control over a company for a limited period would not be objected to.

Nehru took this stand much against the dislike of his party and India’s leading industrialists who in their economic document, the ‘Bombay Plan’, inter alia, had advocated preference for loans and foreign aid over foreign investments and batted for protectionism. It was due to Nehru’s cautiously liberal approach to foreign investment that India’s foreign direct investment stock, as pointed out by the economist, Nagesh Kumar, more than doubled from Rs 2,560 million in 1948 to Rs 5,665 million in 1964.

An integral aspect of Nehru’s economic vision was the absence of large-scale,ideology-driven nationalisation of private investment of the kind that had happened in Soviet Union, China, and other countries. Nehru’sviews against nationalisation or expropriation of investment also extended to foreign capital. In the few instances of nationalisation of foreign investment, such as the Imperial Bank of India in which British shareholders had a 10 per cent stake, full compensation was paid to the foreign investors.

Although Nehru was inspired by the Soviet Union’seconomic model and believed in creating a socialist society, he was also fully aware of the excesses of communist regimes. The fact that the Indian approach to foreign investment differed from countries like China is even more remarkable given that both India and China, as the international lawyer, M.Sornarajah, argues, “shared[a] colonial experience in which foreign investment and international trade were the basis of subsequent political domination”.

Nehru’s India didn’t turn its back on foreign investment despite experiencing colonial rule. Foreign capital was welcome if it could assist in India’s development and help the private sector. Nehru’s approach was consistent with that of an economic nationalist. In purely economic terms, once the development of heavy industries was considered necessary, permitting foreign investment became an imperative.

Nehru, like all leaders, should be questioned and critiqued. But this critique should be based on context and the times in which he lived and worked.

Prabhash Ranjan is Professor and Vice-Dean, Jindal Global Law School, O.P. Jindal Global University