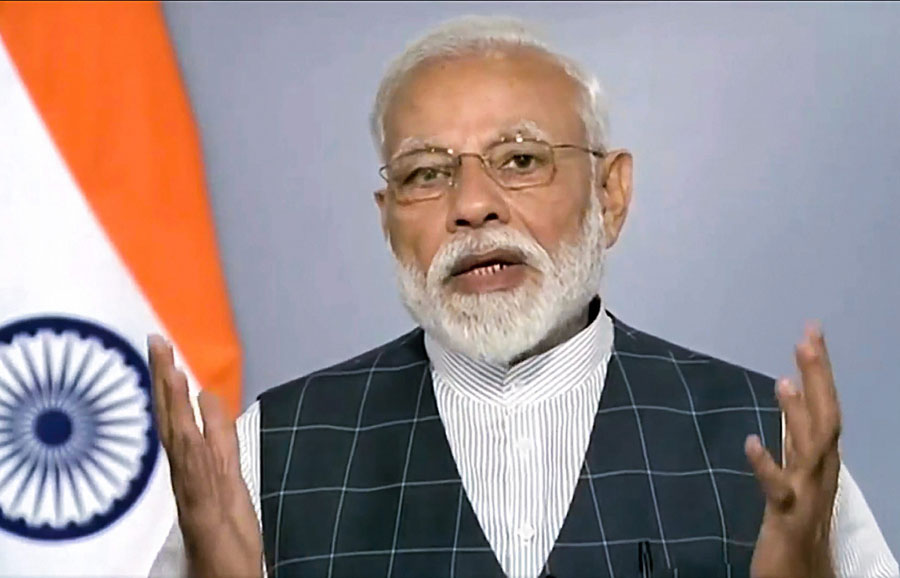

The idea of conducting simultaneous elections for the Lok Sabha and the state assemblies has resulted in spirited deliberations. The debate has been kindled, once again, with the prime minister announcing the formation of a committee to examine an issue that has defied resolution. One reason for the persistence of the knots is that both sides in this debate are convinced about the merit of their arguments. Those who support the ‘one nation, one election’ principle — Narendra Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party are enthusiastic proponents — point out that such a joint exercise has had precedents. They also vouch that simultaneous polls can ease the financial strain caused by India’s demanding electoral calendar. There is also the argument that the imposition of the model code of conduct necessitated by frequent elections puts a spanner in the works of development programmes apart from keeping the government preoccupied with politics and not policy. But the criticisms against Mr Modi’s ‘one nation, one poll’ initiative cannot be wished away either. The general elections for the 17th Lok Sabha were staggered across seven phases. Holding elections for Parliament and states together could then become an impossibly long-drawn exercise and pose a formidable logistical challenge. Seven of the 17 Lok Sabhas have had to be dissolved before the expiry of their terms; mid-term elections are not exactly a novelty in the states either. What about elected governments that do not complete their tenure at the time of a Lok Sabha election? Would they be removed? These eventualities need to be addressed. Yet another grouse is the belief that synchronized elections could unfairly brighten the prospects of national parties vis-à-vis regional ones. The Opposition alleges that Mr Modi’s endorsement stems from this perceived advantage.

An issue as sensitive and crucial as this requires patient, informed debate. The prime minister’s decision to call an all-party meeting for discussion was promising. But the absence of key Opposition parties — the Congress, Trinamul Congress, Bahujan Samaj Party and the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam were notable absentees — defeated the very purpose of the meeting. Lessons must be learnt from this failure in both camps. The government — it has a brute majority — needs to reach out effectively to the Opposition to facilitate meaningful dialogue. The Opposition must reciprocate as well. The future of India’s elections hinges on a constructive engagement.