This month, we observe the anniversaries of three eminences in ways that have turned farcical, even fraudulent. It would have been a mercy had we stopped at lip service as the annual rites of remembrance; we’ve brutally wolfed those legacies.

The first among the three is, of course, the man who has become familiar to us, courtesy his round-rimmed glasses embossed on ‘Swachh Bharat’ tumblers and streamers. October 2 became an occasion to trigger a rampant online celebration of his assassin, such is also our manner now of greeting the man we call Father of the Nation.

The other two are entities we routinely invoke and consign where they belong for safekeeping — in the shuttered almirahs of necessary hypocrisies. One belonged to Akbarpur in east Uttar Pradesh and died on October 12 nearly half a century ago. The other came from Sitabdiara, a riverine island between the Ganga and the Ghaghra on the shifting margins between eastern Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. He was born on October 11.

Both travelled West to study as young men during the first half of the twentieth century. Both turned to public life during the freedom movement under the Congress canopy. Both were protégés of Jawaharlal Nehru and occupied the socialist precincts in the party. Both rebelled in later years, turned critics of Nehru, and became rallying posts of anti-Congress politics.

The man from Akbarpur chose pre-war Germany for further studies, if only to thumb his nose at imperial Britain and its educational institutions. He returned as anti-capitalist as he was anti-Marxist. Capitalism he called the “rich man’s exploitation machine”; Marxism he called a fad and Europe’s ideological tool against Asia, a system that imposed the dictatorship of a party over people.

He espoused a home-minted socialism moored to social and economic equality, medium enterprise, and a notion of government as servant rather than ruler of the people. He wanted governance drastically decentralized and people given the right to recall governments. He was against the mildest police action against democratic protest. He was militantly anti-English, which he called the language of imperialists and the ruling elite. Nehru and the Congress he closely associated with that elite. The first non-Congress, multi-party governments to assume power in the northern states in 1967 were chiefly a consequence of his efforts.

He was a feisty battler at home and abroad. Nehru had noticed the internationalist in him and picked him to head the foreign affairs cell of the Congress in the 1930s. He joined anti-racism barricades in the United States of America, anti-imperialist marches across Europe, and jati-todo (banish-caste) crusades in India; sau mein saath was his maxim on castes, that backward castes should get a 60 per cent share in politics and governance, commensurate with their share of the population. He travelled incessantly, wrote copiously, lived an erratic on-the-road life, and became somewhat of a legend in his lifetime, a rough-hewn radical who spawned a distinct school of socialism; its many alumni, though divided and scattered across political parties of North India, continue to inform the political discourse of their dummy hero’s memory, though not his ideals.

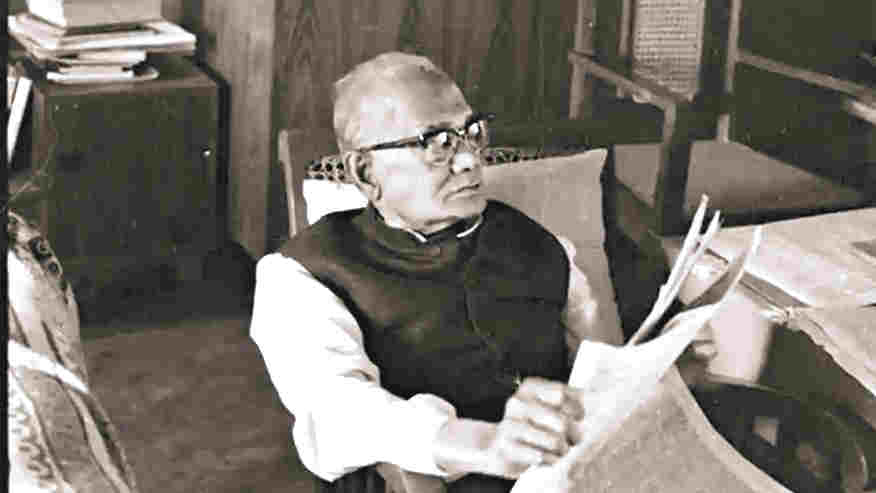

Ram Manohar Lohia. ABP Archives

After breaking from the Congress and launching the Samyukta Socialist Party, he unveiled a seven-fold manifesto, what came to be known as the sapt-kranti, the seven revolutions: gender equality, end of discrimination based on caste and colour, liquidation of colonialism and the establishment of a world parliament, end of inequality generated by big capital, growth through decentralized planning, mass civil disobedience, and end to armaments. He was a maverick. After the Chinese left India militarily and psychologically bruised in 1962, he called for developing a nuclear bomb.

He died early and unexpectedly after a minor prostate-related surgery in 1967, probably of accumulated excesses and neglect of a lifetime; he chain-smoked and drank coffee and tea incessantly, he barely bothered with eating.

The man from Sitabdiara went to Berkeley to study sociology in the early 1920s after finishing as a merit scholar at Patna’s Bihar Vidyapeeth, a Congress-driven school. There, to pay his fees, he laboured on vineyards, packed fruits at a canning factory, washed dishes, worked at a car garage and in a slaughter house, sold lotions and accepted casual teaching jobs. But Berkeley was still unaffordable and he moved to Wisconsin, where he turned animated over the Bolshevik consolidation in Russia, read Marx and Engels, and became a communist. On returning home, he found his young wife, Prabhavati, deeply immersed in Gandhian practice. She had left their Patna home and moved to the ashram on the Sabarmati. She might have had some influence in her husband joining the Congress rather than India’s fledgling Communist Party. All his life, he swivelled uncertainly between a Fabian brand of socialism and Gandhian beliefs; he wore khadi and, often, even joined his wife on the charkha, Gandhi’s emblematic spinning wheel.

He remained in the Congress much longer than the man from Akbarpur, although he grew disenchanted with power politics and refused to contest elections. He became a near-recluse in his Patna home, which Prabhavati’s mission had turned into a spartan Gandhi ashram. He turned, for a time, to the Gandhian sage, Vinoba Bhave, and his benevolent Bhoodaan, or voluntary land donation, movement, but not with any great conviction or commitment, it appeared. He took a tolerant view of Nehru’s promotion of daughter Indira and, later, of her accession to power. He often advised her, and ran freelance missions for her, such as a roving ambassador to convince world capitals why India was intervening militarily in East Pakistan.

But soon thereafter, he turned vociferously anti-Indira and came to be adopted as the patriarch of many oppositional currents to the Indira Congress: the socialists, the Jan Sangh, a wing of communists, ultra left-wingers, angered student activists protesting price rise and political authoritarianism. When Indira Gandhi swung against the motley, burgeoning collective, imposing the Emergency and putting many leaders, including the Sitabdiara elder, into jail, the tide against her thickened. He was freed on grounds of failing health, but he took to the streets and called for Total Revolution, an ambiguous charter, but, at that time, catchy and effective. He came to lead what many prefer to call India’s second Independence movement — the overthrow of the Emergency and the return to democratic elections in 1977, which put the first non-Congress government in power in Independent India. He mentored the government, never joined it, and died a bitter man looking out of the window of his Jaslok Hospital bed in Bombay, watching his pupils tear at each other and bring the non-Congress experiment down.

This man was known as Jaya Prakash Narayan, or JP. One might wonder how he’d have viewed the state of civil rights and fundamental constitutional freedoms in India at the moment.

The man from Akbarpur was called Ram Manohar Lohia. One might wonder what he’d have said of what’s transpiring around Hathras, and how he might have thought to

respond.

One might also wonder, and wonder deeply, why none of the three — neither Gandhi nor JP nor Lohia — ever held office in this nation of ours.

sankarshan.thakur@abp.in