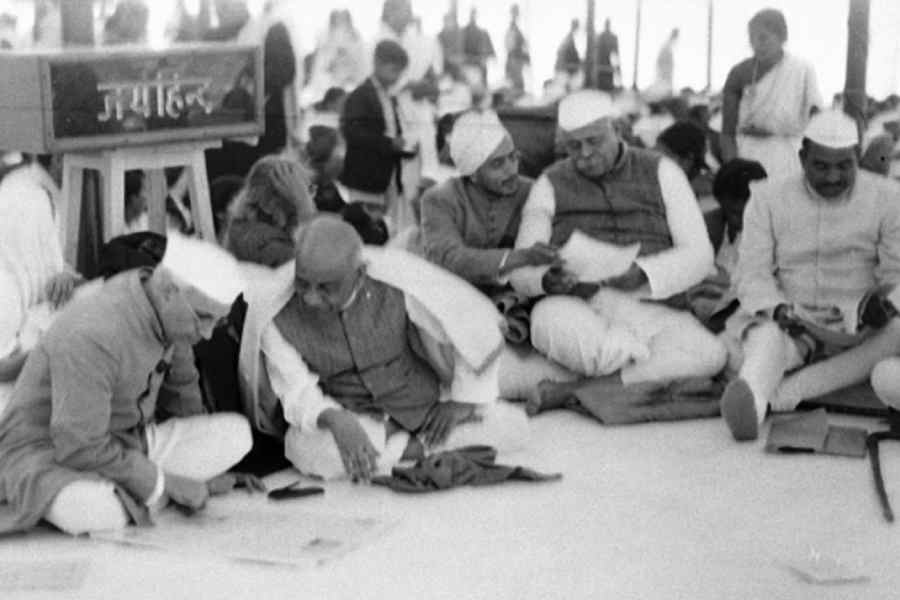

Later this month, we shall mark the sixtieth anniversary of the death of India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru. This column focuses on one key aspect of Nehru’s political career — his collaboration with Vallabhbhai Patel. These two men worked shoulder-to-shoulder during the freedom struggle and in the early years of Independence. They had their disagreements, as any two individuals working together would, whether as fellow members of a cricket team, or spouses in a marriage, or directors in a company. Yet, when one looks at their relationship in its entirety, it was emphatically a partnership in which their distinctive strengths were pooled together in the service of the land they both so deeply loved. This essential complementarity is denied by Narendra Modi and his party colleagues who miss no opportunity to denigrate Nehru and elevate Patel at his expense.

When the British ruled us, Nehru and Patel helped make the Congress a mass organisation representative of most sections of Indian society. Both spent many years in jail. Yet perhaps even more important was their work in the first cabinet of free India. The British left this land in a state of division and disrepair. Perhaps no new nation was born under more unpropitious circumstances; against the backdrop of civil war, scarcity and privation; deep inequalities of caste, class and gender; the problem of the five hundred princely states to be integrated; the problem of several million refugees to be resettled. That the country was nonetheless united, and brought under a democratic template between 1947 and 1950, was the handiwork of many remarkable patriots, among whom perhaps Nehru and Patel were paramount.

The contributions of Nehru and Patel in building the foundations of the Republic have been detailed in my book, India after Gandhi, and in other works too, such as Rajmohan Gandhi’s superb and still unsurpassed biography of Patel. Nehru focused on the emotional integration of India by assuring equal rights to women and to members of ethnic, religious, and linguistic minorities. He energetically advocated multi-party democracy based on universal adult franchise and was an inspirational figure for the young. Patel focused on the territorial integration of India by bringing the princely states on board; he played a vital role in reforming the civil services and in forging a consensus on the Constitution as well.

History records how fortunate Indians were that, in those conflict-ridden early years of our nationhood, we had Nehru and Patel working shoulder-to-shoulder. In public and in private, they often expressed their enormous regard for each other. In September 1948, Patel wrote to a younger colleague to clear the latter’s mind “of the misimpression you have got about myself and Jawaharlal going to part. There is absolutely no truth in the matter… Of course, there are differences of opinion between us, as all honest people have. But that does not mean that there would be any difference between our mutual regard, respect, admiration and confidence.” A year later, in a tribute to Nehru on his 60th birthday, Patel wrote that “having known each other in such intimate and varied fields of activity we have naturally grown fond of each other; our mutual affection has increased as years have advanced, and it is difficult for people to imagine how much we miss each other when we are apart and unable to take counsel together in order to resolve our problems and difficulties.”

This admiration was reciprocated. In August 1947, Nehru wrote to Patel hailing him as “the strongest pillar of the Cabinet”. Three years later, when Patel died, Nehru described his late friend and colleague as “a great captain of our forces in the struggle for freedom and as one who gave us sound advice in times of troubles as well as in moments of victory…” Praising Patel’s “matchless courage, inflexible sense of discipline, and genius for organisation,” Nehru said that “in particular, his genius was demonstrated in the way he handled the difficult and complicated problem of the old Indian States. He fixed his goal, a united and strong India, and set about to achieve it with skill and determination.” Nehru ended his tribute by saying: “It is for the people of this country to follow [Patel’s] shining example, his devotion to duty, his steadfastness, his sense of discipline, and thus to realise in ever growing degree that free and strong and prosperous India for which he laboured.”

Works of historical scholarship document how Nehru and Patel were comrades and co-workers both before and after Independence. How then has the public discourse today come to represent them as adversaries and rivals?

The original sin here was that of Jawaharlal Nehru’s own family. In January 1966, Nehru’s successor as prime minister, Lal Bahadur Shastri, died of a heart attack, aged only sixty-one. The Congress bosses now chose Indira Gandhi to succeed Shastri, thinking they could control her. They were grievously mistaken as Mrs Gandhi asserted her authority over the party. She further burnished her credentials through the abolition of the privy purses and her leadership during the Bangladesh War. Now, thinking herself to be in complete command of the party and the government, she set about converting the Congress into a family firm.

Mrs Gandhi was not entirely unmindful of Vallabhbhai Patel’s contributions to nation building. It was in 1974, when she was prime minister, that the National Police Academy was named after the Sardar. However, she placed much more emphasis on promoting her father’s memory, as for example by naming a showpiece new university after him. When Rajiv Gandhi became prime minister, this glorification of Nehru at the expense of Patel (and other nationalists) got even greater impetus, as in the State sponsored tamashas during the Nehru Centenary in 1989. At the same time, Rajiv sought to place his mother on the same level as his grandfather, naming the capital’s airport after her.

Indira and Rajiv began the work of making the history of the Congress the story of a single family. The process was furthered by Sonia Gandhi after she became Congress president in 1998. For her understanding of the party’s history had no space for Vallabhbhai Patel; nor indeed for Congress stalwarts such as Azad, Kamaraj, Sarojini Naidu and many others. Sonia’s Congress nodded occasionally in the direction of Mahatma Gandhi; otherwise, party history was equated with the history of one family. The Congress leaders chosen to be honoured and celebrated were Nehru, Indira and, above all, Rajiv. Between 2004 and 2014, several prestigious public projects were named after Rajiv Gandhi, while a great deal of public money was spent on commemorating his birth and death anniversaries as well.

As an RSS pracharak, Narendra Modi was taught to worship at the shrines of K.B. Hedgewar and M.S. Golwalkar. As a BJP organiser, Modi was asked to admire Shyama Prasad Mookerjee and Deen Dayal Upadhyaya. He came to proclaiming his admiration for Vallabhbhai Patel relatively late in his career, after he became chief minister of Gujarat. His public promotion of Patel intensified around 2012 when he made his prime ministerial ambitions evident. In Modi’s wake, the BJP began actively praising Patel too.

As the writer and public servant, Gopalkrishna Gandhi, has remarked, it was only because the post-Nehru Congress disowned Patel that Narendra Modi’s BJP has been able to “misown” him. They have built a grand memorial to him in Gujarat and now invoke his name at every opportunity. In a tragic irony, a lifelong Congressman has become the symbolic property of the BJP.

There are good reasons for Modi and the BJP to dislike Jawaharlal Nehru. Nehru’s secularism grates on their majoritarianism; his cosmopolitanism is at odds with their xenophobia; his admiration for modern science runs counter to their superstitious belief that ancient Hindus once knew it all; his exuberant love of life challenges their puritanical and humourless selves. However, the manner in which Modi and the BJP have used Nehru’s great comrade, Vallabhbhai Patel, as a stick to decertify and diminish India’s first prime minister would have appalled Patel himself. The Sardar may have watched with amused indulgence Sonia Gandhi’s equation of family history with the Congress’s history; but his fury would have known no bounds at the BJP’s pernicious misuse of his name and legacy to break apart, in death, a partnership that stood the nation so well in real life.

Jawaharlal Nehru and Vallabhbhai Patel constituted the first of many jugalbandhis that have shaped politics and statecraft in independent India. Later examples include Indira Gandhi and P.N. Haksar, Atal Bihari Vajpayee and L.K. Advani, Manmohan Singh and Sonia Gandhi, and, most recently, Narendra Modi and Amit Shah. Writing as both citizen and historian, I can say with some confidence that Indians were enormously lucky to have Nehru and Patel in those crucial early years. Of all the political partnerships in our modern history, theirs was the noblest as well as the most necessary.

ramachandraguha@yahoo.in