“The history of the world is but the biography of great men,” wrote the British historian, Thomas Carlyle, in the nineteenth century. Even leaving aside the misogyny, the statement was a very elitist one. The rise of Marxist history, among others, undermined the ‘Great Man theory’ and foregrounded ‘ordinary people’ as the drivers of history, variously known as the masses, common people, mob, crowd, proletariat and so on.

As children, we were told to disabuse ourselves of the perception of history as the story of kings and warriors and to buy into a notion of ‘real’ history as an account of ordinary people. It is thus that we came to acquire books that undermined histories focusing primarily on great empires and famous dynasties, such as Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States (1980), a pioneering, bottom-up history that helped to dismantle the dominant and disempowering trope that US history was ‘made’ by Great White Men.

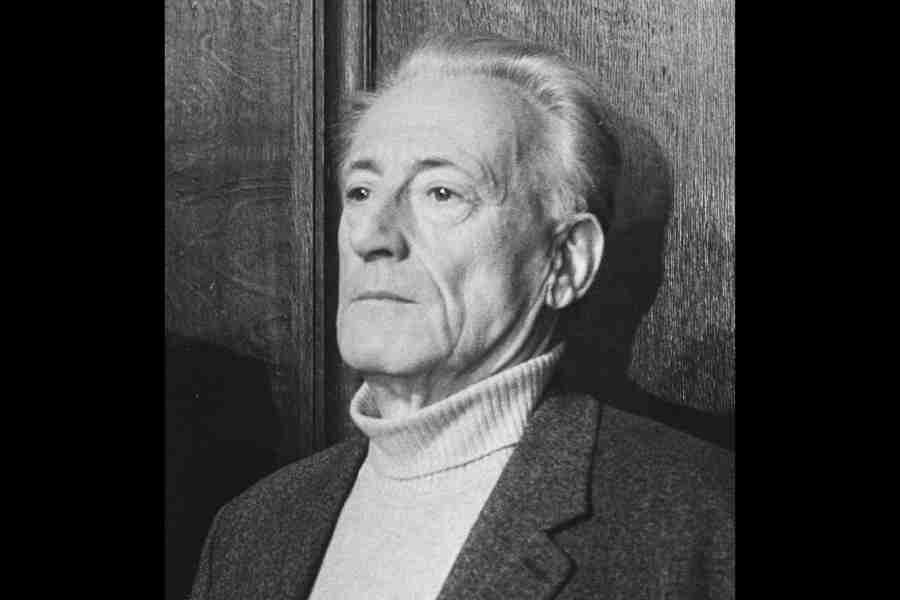

Ordinariness has always been closely associated with the concept of the everyday or the quotidian. The routines of everyday life are mundane and tedious — something that T.S. Eliot, in “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”, memorably likened to measuring out one’s life with “coffee spoons”. The everyday life of people has always held a great deal of interest for scholars, and the French sociologist, Henri Lefebvre, wrote, between 1947 and 1981, his three-volume magnum opus, later translated as Critique of Everyday Life. The book’s purpose was to demonstrate that the everyday should not be exempted from philosophical scrutiny, especially since it was this domain of life that opened itself most effectively to a conquest by capitalism. As technology, one of corporate capitalism’s greatest props, keeps tightening a chokehold on every moment of our daily lives, Lefebvre’s assessment sounds well-taken and prophetic.

The ‘people’s histories’ we began with were about ‘ordinary’ people. But one problem was that they were present in these histories only as an abstraction, as sort of molecules that namelessly and facelessly lent themselves to bigger, outwardly impersonal, structures and processes, like slavery, the Enlightenment, industrialisation, colonialism and suchlike. There is no way one can scour the mindscape or lifeway of an ordinary individual from such ‘people’s histories’. There are rare exceptions to this, like life stories of ordinary individuals reconstructed by supremely gifted historians from medieval Inquisition records, most notably Natalie Zemon Davis’s account of the fourteenth-century French peasant, Arnaud du Tilh, in The Return of Martin Guerre, or Carlo Ginzburg’s tale of the inquisitive Italian, Menocchio, in The Cheese and the Worms: The Cosmos of a Sixteenth-Century Miller.

However, the protagonists of both books were accused of ‘transgressions’ — Arnaud of impersonating somebody who had abandoned his wife a few years before, and Menocchio of a heretical reinterpretation of the Bible — which is why they were tried and executed in medieval Europe and immortalised in books of the last century. Even keeping aside the question of the ‘fairness’ of Inquisition trials, those acts of ‘transgression’ were out of the ordinary.

So the question still remains — who exactly are really ‘ordinary people’? Is it possible to write a history of ordinariness? What are its registers? Familiarity, habit, routine, and boredom might, of course, be important aspects of ordinary life but, surely, ordinariness must also be about anxiety and joy, about surprise and accident? How then to catch and document the gentle unfurling of the quotidian routine of mundane, dreary lives and the aspirations to rise above the ordinary?

On this last point, it may be interesting to look at two opposing notions of what kind of human beings we want our children to grow up to be. On the one hand, many of us have read a letter spuriously ascribed to Abraham Lincoln, addressed to his son’s teacher on the kid’s first day at school. It has a litany of exhortations aspiring to plant extraordinary human qualities in an unsuspecting child. From among a flurry of curated entreaties of cliched sentimentality, my favourite is “Steer him away from envy if you can and teach him the secret of quiet laughter!” A stab at extraordinariness indeed!

Now compare this with something quite the opposite — the sobering wish of the poet, Philip Larkin, to a friend’s newborn girl: “May you be ordinary;/ Have, like other women,/ An average of talents… In fact, may you be dull —/ If that is what a skilled,/ Vigilant, flexible,/ Unemphasised, enthralled/ Catching of happiness is called.” Or the counterintuitive exhortation of the poet, William Martin, to parents: “Do not ask your children/ to strive for extraordinary lives… Help them instead to find the wonder/ and the marvel of an ordinary life./ Show them the joy of tasting/ tomatoes, apples and pears./ Show them how to cry/ when pets and people die./ Show them the infinite pleasure/ in the touch of a hand./ And make the ordinary come alive for them./ The extraordinary will take care of itself.” Surely, then, plain, uncomplicated ordinariness, too, may be a ‘virtue’ to aspire for.

In 1932, Rabindranath Tagore wrote a poem titled “Sadharan Meye” (The Ordinary Woman), which narrated the story of an ‘ordinary’ girl whose lover had left her and run off to England, presumably enjoying the company of pretty and accomplished women on those shores. The girl in the poem implores the novelist, Sarat Chandra Chatterjee, to write a story about her in which she would be sent abroad, get a first in mathematics, and be given a grand reception in which famous people and scholars would vie for her attention, with her former lover watching all of this, forlorn, from a corner. In this aspirational account of wish-fulfilment, the registers of ordinary women’s lives were different — everyday sorrows of marginalisation, rejection, abandonment and the like, so that redemption, even victory, was only possible in fiction.

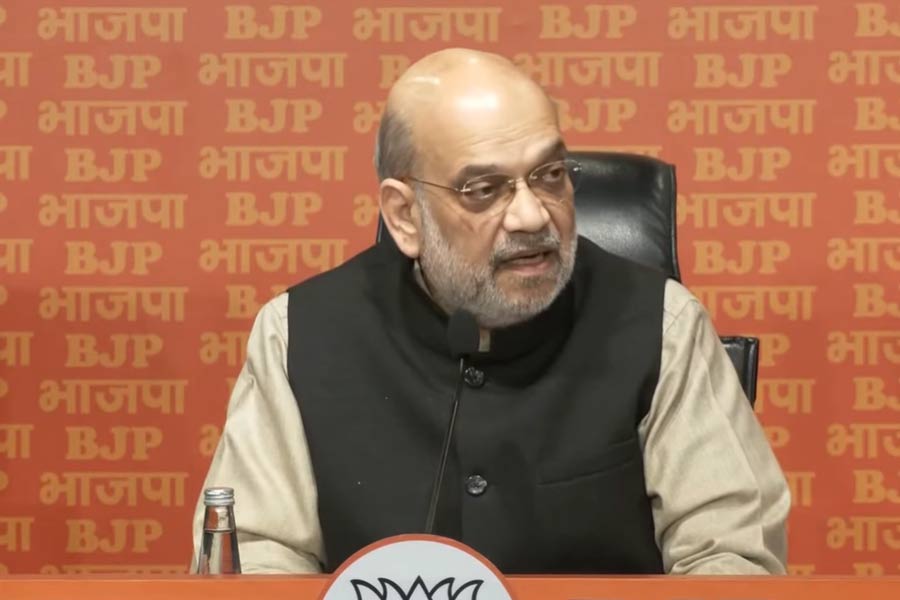

One of the most striking voices ever commenting on Indian socio-political life through his cartoons was R.K. Laxman, who immortalised the figure of the ‘Common Man’, the ageing, bald man in a checkered jacket, wearing an eternally bemused look as he trudged through daily scenes of hypocrisy, duplicity, deceit, and corruption. One possible reason why we came to love the ‘Common Man’, who represented the ordinary citizen, is that even in his perpetually beleaguered state he seemed to represent not an uneducated or ignorant mind, but praiseworthy virtues, like simplicity and kindness, decency and common sense. This is how ordinariness can be elevated or valorised as the bedrock of social normalcy and decency, especially at a time of pervasive intolerance, greed, and corruption.

But lest we forget, ordinariness can have a dark side as well. The German-American philosopher, Hannah Arendt, coined the phrase, “the banality of evil”, to describe the phenomenon of ordinary people committing atrocities without awareness, care, or choice. Atrocities like the Holocaust, and some of history’s worst war crimes, were committed not necessarily by psychopaths, fanatics, or sadists, but by ordinary people. The ‘normality’ of individuals who commit such crimes can be terrifying. There is no doubt that as we relate to and identify with the beleaguered ‘common man’ in an era of unchecked intolerance, fathomless selfishness, rampant corruption, and the ascendancy of fake news, we forget that it is we who allow all of this to become normalised and, thus, become complicit in this ‘banality of evil’. A history of ordinariness in contemporary times must, therefore, reckon with a landscape where the lines between decent simplicity and quotidian evil are blurred.

Jayanta Sengupta is Director, Alipore Museum; jsengupt@gmail.com