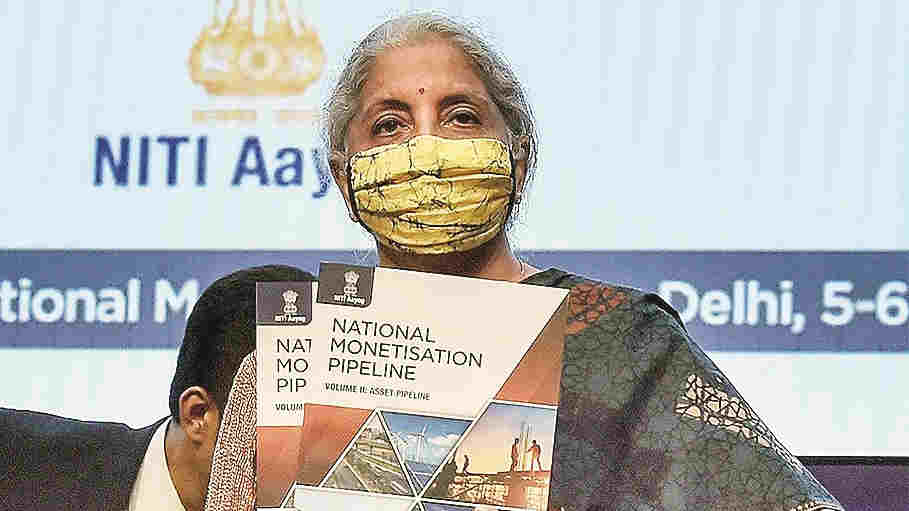

The Narendra Modi government has announced a plan of “asset monetisation” worth 6 lakh crore rupees. This is in addition to its proposed privatization of public sector assets. Asset monetization is supposed to be different from privatization as it involves no transfer of ownership. But if a public asset that was earning Rs 50 crore per year earns Rs 500 crore by being handed over to private management that uses it for unbridled commercial purposes, such as railway platforms becoming advertisement spaces and high-rise malls coming up above roadways, then this move, per se, while squeezing out ordinary users, does not help the government. What matters to the government is the amount it gets for such a handing over, whether on long leases or only for a certain period. Asset monetization is thus analogous to sale, although for varying periods of time. However, what I say below holds, no matter for how long the asset is handed over.

My point is that it has absolutely no economic rationale. The claim that it represents an alternative, less harmful, way of financing government spending compared to a fiscal deficit is wholly mistaken.

Let us compare three ways of financing, say, Rs 100 of government spending, and assume for simplicity a closed economy (relaxing this assumption would only complicate, not negate, our argument). The first is through a fiscal deficit. Since in a closed economy investment must equal savings, a fiscal deficit, which by definition represents an excess of government investment over government savings, must be matched by a corresponding excess of private savings over private investment. Since private investment, determined by past decisions, remains unchanged during the period, private savings must increase by the amount of the fiscal deficit. A fiscal deficit increases demand, which raises output (if unused capacity exists) or prices relative to money wages (if there is no unused capacity). Private savings increase either way: larger output means more savings as do larger profit margins.

A fiscal deficit thus puts into private hands the very extra savings (over the initial level) that the government borrows. Since savings represent addition to wealth, a fiscal deficit invariably puts extra wealth into private hands quite gratuitously. John Maynard Keynes had called this extra wealth a “booty”, which lands on the “lap” of the capitalists.

Now, consider a tax on wealth, or on surplus (the source of private savings). The government, whose spending of Rs 100 would otherwise have put extra wealth of Rs 100 into private hands (if financed by a fiscal deficit), now simply takes away this extra wealth through such a tax, which leaves the private sector no worse off than prior to the government’s fiscal intervention. An increase in revenue from a wealth tax or a profit tax to finance larger government spending does not represent any sacrifice on the part of the surplus-earners. It only takes away from them the extra wealth that would have otherwise gratuitously accrued to them if the spending had been financed by a fiscal deficit.

Now consider the third option: selling public assets to finance government spending. This is actually no different from the first option, namely, using a fiscal deficit to increase government spending. In the first case, the increase in private wealth corresponding to increased government spending takes the form of an addition to private holding of government IOUs (securities), while, in the third case, it takes the form of private holding of public assets. Thus, only the form in which the increase in private wealth is held changes, otherwise the two cases are identical. In Keynes’s language, the “booty” on the capitalists’ “lap” takes the form of public assets rather than government securities.

Two specific aspects in which the cases are identical should be noted. First, the very resources with which public assets are purchased by private surplus-earners are put into their hands by government spending; and this is entirely because of the government’s decision on how to finance spending, not because they have done anything to “earn” them. It represents a gratuitous transfer to their pockets by the government.

Second, private savings go up and add to private wealth for precisely that section of the population which does the overwhelming bulk of private savings anyway and hence holds almost the entire private wealth. (In fact, well over half of the population in India has an income so low that it can scarcely afford to save.) This has the effect, therefore, of adding to the wealth of those who already have massive wealth. This entire fiscal exercise engineers a gratuitous increase in the wealth of the already wealthy.

This, and not the usual argument advanced against it, is also the problem with financing government spending through a fiscal deficit. The usual argument is that a fiscal deficit causes excess demand and hence inflation. But in an economy characterized by massive foodgrain stocks and unutilized industrial capacity because of insufficient aggregate demand, an increase in the fiscal deficit would have no inflationary consequences of this sort. The inflation that is currently occurring in the Indian economy is caused not by excess demand, but by “cost-push” factors, primarily higher indirect taxes on petro-products and their cascading effect. Hence, the real reason why direct-tax-financed government spending is to be preferred over fiscal-deficit-financed government spending is not that the latter is inflationary, but that the latter puts more wealth in the hands of the already wealthy. This is also true for government spending financed by the sale of public assets.

A point must be noted here about the argument that the resources used for buying public assets are handed to the surplus-earners by government spending itself. The resources, amounting in our example to Rs 100, are put into the hands of the private surplus-earners as a whole; but not all of them buy public assets, only some do. Among the surplus-earners, therefore, there is a redistribution of resources whereby those who buy public assets do so by borrowing, directly or indirectly, from others within this surplus-earning class. The buyers of public assets may do so by borrowing from banks, other financial institutions or financial markets, but the resources they borrow are equal to what other surplus-earners have got. A set of complex portfolio adjustments, involving financial intermediaries, are made, through which the Rs 100 that the government obtains from the sale of public assets is actually put into the hands of those who buy them, by the government’s own spending.

It may be thought that those who buy public assets, because their debt goes up for doing so, will consume and invest less than if government spending had been financed by a fiscal deficit; that is, our case three will be less expansionary for the economy than our case one. But this is untrue. Investment, determined by past decisions, remains unchanged anyway in the period under discussion; and consumption, typically a given fraction of surplus-earners’ income, has no reason to be different between cases three and one. Selling public assets thus is no less expansionary than running a fiscal deficit.

All this has been known for almost nine decades, ever since the Keynesian Revolution, but the Modi government remains unaware of it. Public asset monetization, like public asset sale, for financing government spending betrays as much a poverty of economic thinking as a shamelessly pro-rich bias on its part.

Prabhat Patnaik is Professor Emeritus, Centre for Economic Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi