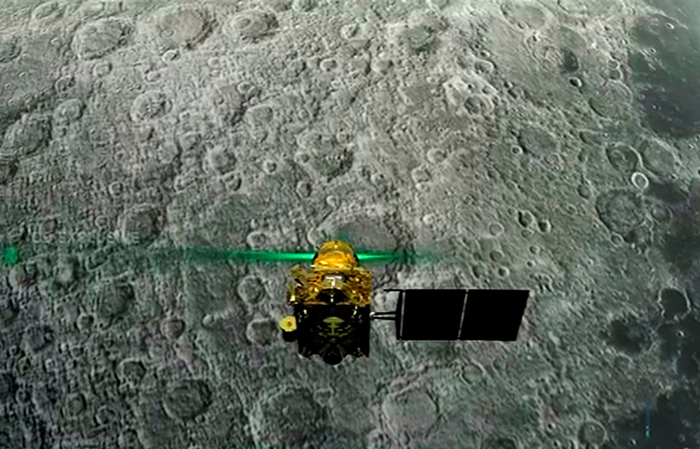

The failure of Vikram, the landing vehicle of Chandrayaan 2, to make a soft landing on the dark side of the moon was a frustrating end to an otherwise remarkably successful Isro mission. From the delayed but perfectly executed launch on July 22, to Vikram’s success in separating from the orbiter and achieving low lunar orbit on its own, this was a textbook example of big thinking on a budget.

Coming as it did in the wake of Isro’s Mars Orbiter Mission, Mangalyaan, which famously reached Mars for the price of one of Hollywood’s make-believe space fictions, soft-landing Vikram and mobilizing Pragyaan, the lander’s wheeled lunar rover, would have made for a fairy-tale ending. The ‘fifteen minutes of terror’ — the duration of the lander’s descent — flagged before the event by Isro’s chairperson, K. Sivan, turned out to be fatal.

The mission’s principal technological and scientific objectives — soft-landing on the lunar surface, operating a robotic rover and using the rover to explore the incidence of water and ice in the moon’s south polar region — will have to wait upon Chandrayaan 3. Soft landings are incredibly complex affairs and historically less than half of those attempted have succeeded. The lander needs to reduce horizontal speeds to nearly zero before the final vertical descent and in the case of Vikram, something went wrong at that stage. Still, it’s important to acknowledge how precise, frugal and capable Isro was in the actual business of space voyaging before that final malfunction.

There is something interestingly old-fashioned about Chandrayaan 2’s ‘Made in India’ credentials. Everything about the mission was indigenous: the GSLV MK III launcher, the orbiter, the lander and the rover were all developed in-house by Isro. Originally Roscosmos, the Russian equivalent of Isro, was meant to contribute the lander, but when it failed to meet deadlines, Isro decided to develop every module of Chandrayaan 2 on its own.

Schoolchildren in the 1960s and 1970s were taught to be proud of the Indian economy’s ability to produce everything from a pin to heavy machinery. Given the Hindu rate of growth that this commitment to autarky produced, it wasn’t surprising that after liberalization the idea of self-sufficiency as a national virtue lost all currency. India’s attempt to create an indigenous defence industry was all but abandoned for the very good reason that the DRDO’s ambitious projects ran aground.

India’s attempt to indigenously develop a Main Battle Tank, Arjun, is a cautionary tale. Over budget and grossly over schedule, the majority of these tanks were grounded because of a lack of spares. Ironically, for an allegedly indigenous MBT, these garaged tanks were mobilized by importing those missing spares because many of the tank’s crucial components were sourced from Israel, Germany, even South Africa. The army voted with its feet by equipping its tank brigades with T-90s bought from Russia.

But unlike the DRDO, Isro has been a poster boy for State-sponsored research and development. In a world where space exploration is being rapidly privatized, with Elon Musk’s Space X and Jeff Bezos’s Blue Origin making Nasa seem like a lumbering sarkari behemoth, Isro sails serenely on, from one success to another. If the Nehruvian dream of the enlightened State creating dynamic public sector institutions ever made landfall, it was with Isro.

Isro’s origins are classically Nehruvian: like Homi Bhabha and the department of atomic energy, Vikram Sarabhai was the visionary scientist at whose urging the State created an institutional space for self-sufficiency in science and technology. But unlike many Nehruvian public sector organizations, Isro produced a string of greatest hits, from sophisticated satellite launch vehicles to geo-stationary satellites to planetary and lunar space missions. Chandrayaan 2’s near miss was only the latest of Isro’s many achievements. Since so much ink has been expended in documenting the inefficiencies of State-run institutions, it might be useful for sociologists to explore Isro’s institutional culture to understand what made this PSO so successful.

In 2014, immediately after Isro’s Mars Orbiter Mission, Mangalyaan, successfully achieved Martian orbit, a photograph went viral in India. It was a picture of scientists in Isro, many of them women, in their saris and bindis, flowers in their hair and lanyards round their necks, celebrating their achievement with smiles and victory signs. One reason why Indians fell in love with that photograph was that the scientists in it looked like their working mothers and sisters. These could have been women teaching in public universities or working in government offices. And, after a fashion, they were.

Isro began in 1962 as Incospar, the Indian National Committee for Space Research. The moving spirit behind Incospar was Vikram Sarabhai, but we should credit Nehru for having the good sense to listen to visionary advice. The distinguished Pakistani physicist, Pervez Hoodbhoy, recently wrote that India wouldn’t have had a culture of science education and research had it not been for the first prime minister’s enthusiasm for science and his keenness on the scientific temper. Lamenting the state of science in Pakistan, Hoodbhoy found it bizarre that Nehru was so unfashionable in contemporary India, given that he had laid the institutional foundations of Indian science.

Listening to our current prime minister console a summoned assembly of Isro’s scientists the day after Vikram crashed, I wondered what Sarabhai (after whom Chandrayaan 2’s lander was named) would have made of his paean to Isro’s achievement. The prime minister declared that poets and writers in the years to come would use their lyrical licence to memorialize this apparent failure as a great romance, where Vikram, the lander, infected by the scientists’ love of the moon, rushed headlong into her arms.

Narendra Modi’s forte is the nationalist temper and his speech was framed by the Nation. He began and ended with “Bharat Mata ki jai!” Listening to him congratulate the scientists for their tireless service to the Nation, it became apparent that his interest in science and technology was instrumental: scientific achievement was either an offering to the Mother, or a setting in which She could be exalted. Five years ago, he had addressed another assembly of scientists, doctors in that instance, and he had encouraged them to take their cue from ancient Indian scientists who had, on the evidence of India’s religious and mythological narratives, performed head transplants and produced babies outside the mother’s womb. According to the prime minister, Ganesh, that lovable god of all good beginnings, was the result of an elephant's head being grafted on to a human body by a pioneering plastic surgeon while Karna, Kunti’s oldest son, was the product of advanced genetic engineering.

For Modi, the achievements of Isro’s scientists are of the same order as the miracles worked by India’s mythical ancients and they serve the same purpose: the greater glory of Bharat. This is the opposite of the scientific temper: it’s science as a kind of aarti where the goddess honoured is Bharat Mata. Prime ministers are influential people, their example matters, their actions and words are cues for others. A year after Modi became prime minister the Indian Science Congress had sessions where ‘scientists’ read papers documenting interplanetary travel in ancient India. In a more recent edition of the meet, a university vice-chancellor cited the hundred sons of Dhritarashtra as proof of stem-cell research. V. Ramakrishnan, who won the chemistry Nobel in 2009, called the Indian Science Congress a ‘circus’ that he would never attend again.

Modi’s attitude towards science is of a piece with his attitude towards all forms of intellectual or academic knowledge. Intellectual expertise is useful as a way of staging spectacle, but useless if it’s not. It’s why the prime minister ignored credentialed economists and took the advice of eccentric chartered accountants to ambush India with demonetization. Scientific achievement, for Modi, is just grist for his nationalist mill. As charismatic, long-serving prime ministers, Nehru and Modi have left their mark on Indian science. Nehru’s bequest includes Isro and its works. Modi’s legacy is the Indian Science Congress’s new avatar where science merges with the stories pictured in Amar Chitra Katha and a maha Bharat is born.