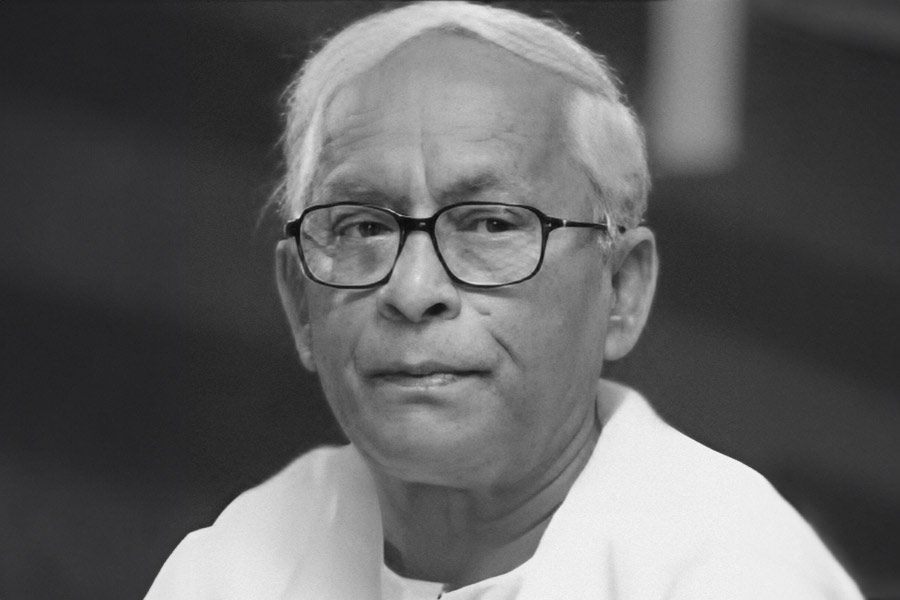

More often than not, old comrades, given the state of communism around the world, are expected to fade away. But Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee, the former chief minister of West Bengal who died yesterday, can be counted as a shining exception to this aphorism. This is because death will not efface Mr Bhattacharjee’s legacy — albeit a mixed one. The veteran leader of the Communist Party of India (Marxist), who occupied the chief minister’s chair for 11 long years, was not the average politician. His interest in the arts, especially cinema and theatre, was a rarity among his peers cutting across party lines. His adherence to rectitude and his aversion to ostentatiousness were a testament to moral integrity, a trait that is uncommon in India’s political fraternity. He was an obedient soldier of the party — a regimented outfit such as the CPI(M) cannot do with dissidence. But Mr Bhattacharjee, unlike his comrades, did strive to change the party and, with it, Bengal’s fortunes. His endeavour to bring business back to Bengal — the CPI(M)’s perverse success in driving capital out of the state notwithstanding — by ushering in industrial projects to Singur and Nandigram bore evidence of a man who was willing to take on the old guard of the regime on the prickly subject of industrialisation. And it did appear that Bengal was willing to dream along with Mr Bhattacharjee, at least for a while. The verdict of the 2006 assembly elections that the Left Front won handsomely could be looked at as a collective endorsement of Mr Bhattacharjee’s slogan of a ‘New Bengal’.

But a dreamer need not necessarily be a doer. One of Mr Bhattacharjee’s abiding failures — hence his chequered legacy — was his inability to proceed with Bengal’s industrialisation with the consent of crucial stakeholders, especially the peasantry. The land agitation in Singur along with the deadly turn of events in Nandigram where lives were lost on account of the heavy-handed approach of the erstwhile administration exposed Mr Bhattacharjee’s Achilles’ heel: he was at once a dreamer and a domineering leader. The slide that began for him and his party with these tumultuous events ultimately led to what had once seemed inconceivable: Mamata Banerjee’s storming of the red bastion. Perhaps a training in the fundamentals of democracy, rather than the strictures of the Little Red Book, would have prepared Mr Bhattacharjee better to deal with the crisis. Was he the right man for Bengal but in the wrong party?