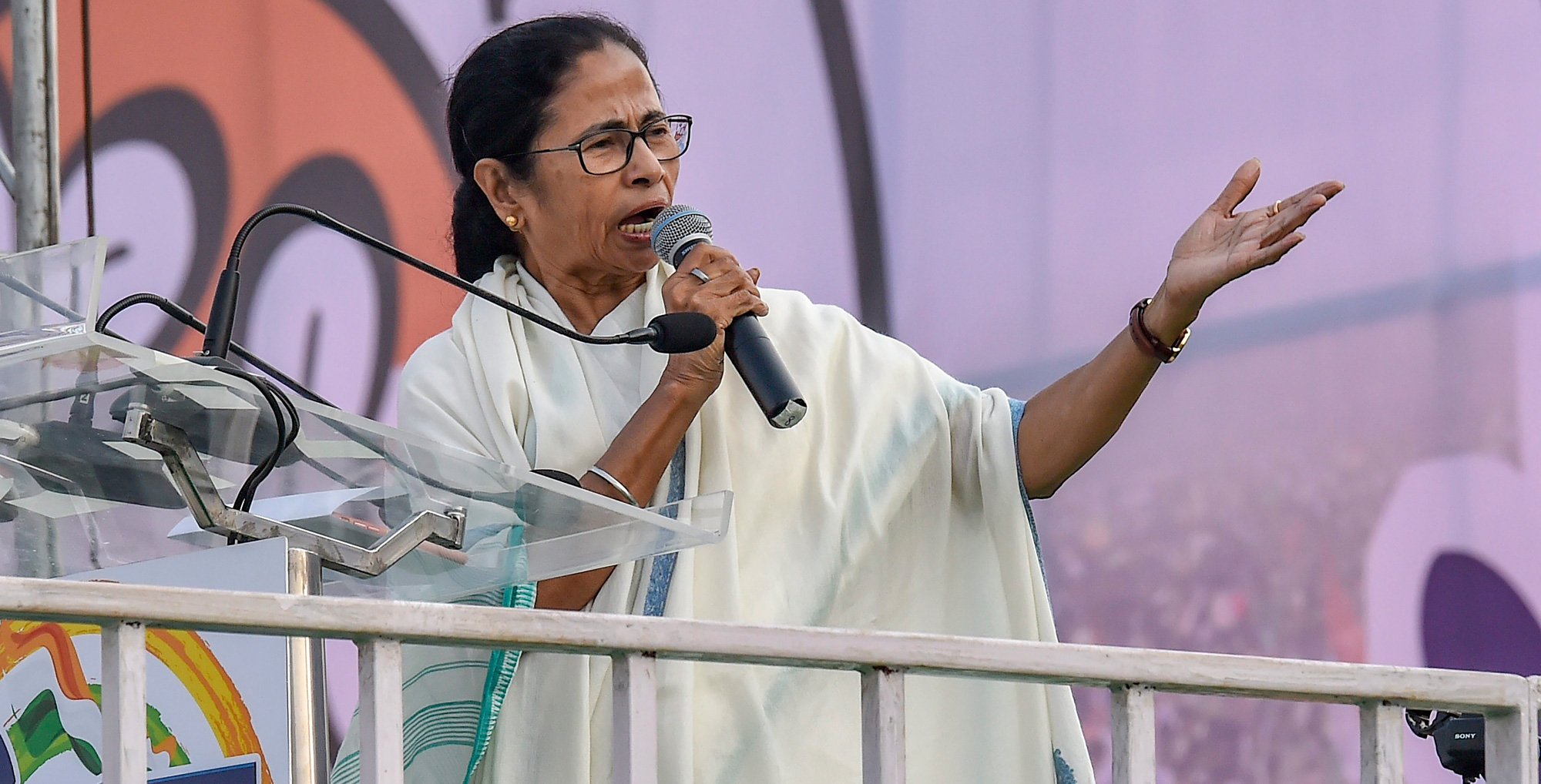

If the mobilization of crowds for a political rally is the yardstick of success, Mamata Banerjee can claim to have won the 2019 general election even before the first vote has been registered in the electronic voting machine. Calcutta has always enjoyed a reputation for being, what Jawaharlal Nehru derisively called, a “city of processions”. But even by the exacting standards set by the Left Front during its three- decade-long domination of West Bengal, the January 19 rally at the Brigade Parade Grounds was super impressive. Only the wilfully blind can deny the state’s chief minister her achievement.

The rally had two principal objectives: local and national.

Within West Bengal, the lavish publicity and preparations for the event and the huge turnout — estimated at around half a million people and maybe more — were aimed at showcasing her political dominance. The Trinamul Congress has literally intimidated all sceptics and its opponents into a state of panic and dejection before the formal election campaign has even got underway.

Secondly, despite the presence of a well-organized Left, Mamata has identified — perhaps quite rightly — the Bharatiya Janata Party as her principal opposition within West Bengal. Yet the BJP in the state remains a fledgling party, and this rally was meant to unequivocally assert that it will remain in its political infancy after the election. Mamata has adopted a steamroller approach, perhaps even emulating tactics which were once seen as the prerogative of the BJP president, Amit Shah. On its part, the BJP has wisely chosen to avoid fighting the West Bengal battle on terms set by Mamata. Rather than focusing on a mega rally in Calcutta, it has chosen to field Shah and the prime minister in sub-regional shows of strength beginning with the one in Malda last Tuesday.

Finally, in an election that promises to centre on the leadership attributes of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Mamata Banerjee was anxious to demonstrate that she was a prime-ministerial contender as well. Invoking regional sentiment in a national battle is her way of trying to neutralize Modi’s pan-Indian appeal. It was significant that almost the entire local media — known in the past to view political rallies as both routine and a colossal civic inconvenience — cheered the January 19 rally with the same crazy enthusiasm reserved for the national side in a cricket World Cup final.

Of course, it was the larger national significance of the January 19 event that hogged the maximum attention. The effort and organization involved in ensuring the presence of 23 political parties and even some renegades from the BJP were commendable. The event received massive national coverage and boosted the morale of the whole galaxy of anti-Modi forces for whom the 2019 election has become a do-or-die battle. Although no member of the Gandhi family was present — they are not known to entertain the idea of playing second fiddle to a regional party leader, especially one who began political life as a lowly functionary in the family firm — and neither was the Bahujan Samaj Party leader, Mayavati, Mamata was at pains to demonstrate that among the regional big guns she was the least difficult. That she spoke with characteristic over-confidence in Bangla, Hindi and English was aimed at scoring a point. The West Bengal chief minister, it would seem, actually wants to be the first Bengali prime minister of India. She has also left no doubt over who her successor in Calcutta will be.

The problem was with the absence of a coherent narrative that will bind the 23 Opposition parties — the Left parties were neither invited nor did they want to attend — together.

There is an argument proffered by Mamata herself that India is experiencing a “super Emergency”, infinitely worse than the one experienced between 1975 and 1977 when the Opposition was imprisoned, the press censored, the judiciary tamed and the Constitution altered — and, by implication, the priority is to dethrone and even prosecute Modi first. The rest, including the question of who will be the next occupant of Race Course Road in the event of a BJP defeat, will be addressed subsequently. No doubt there are activists and other “nattering nabobs of negativism” — a phrase coined by Spiro T. Agnew which was used by the finance minister, Arun Jaitley — for whom Modi is Genghis Khan and Hitler rolled into one. Yet, opinion polls suggest that Modi’s personal popularity remains very high and exceeds that of all Opposition leaders by a big margin. More to the point, while there may be some disappointment that the prime minister hasn’t miraculously brought achche din to India, he is not hated, except by a small section that includes those he refers to as “news traders”. Consequently, raw emotions, while important, haven’t as yet become a substitute for coherent political messaging.

There was no coherent political narrative that was in evidence at the Calcutta rally, apart from the conspiracy theories on the ‘chor’ EVMs. There was an understandable note of triumphalism in the interventions of Hindi-belt leaders, elated over the electoral understanding between the Samajwadi Party and the Bahujan Samaj Party in Uttar Pradesh. The seat adjustment involving two traditional rivals is undeniably a very significant event, and the BJP will have to make superhuman efforts to ensure that it keeps its formidable tally in India’s largest state intact. At the same time, it is very clear that, for the moment, this is an arithmetical aggregation. There has been no intervention by either Mayavati or Akhilesh Yadav to indicate any common thinking on national issues. In the euphoria over the Calcutta rally, this issue has been kept in abeyance but as the campaign proceeds, the internal contradictions and the incoherence of the proposed mahagathbandhan are bound to feature, and with them the spectre of endemic instability.

In her colourful speech, peppered with recitations of iconic Bangla songs and poems, Mamata spoke of a lakshman rekha the government has crossed: it has launched investigations (of financial impropriety) against political leaders. “I too have not been spared,” she said before fulminating angrily about how much money “they”, presumably meaning Modi and the BJP, have stashed away in foreign lands. She threatened retribution.

Judging by the quantum of emotion she expended on it, this was an issue that agitated the chief minister the most. Presumably, there are details that have not entered the public domain. However, what is striking is that she believes that the norms of democracy involve granting a blanket immunity to all political leaders for all suspect financial transactions. It is, above all, an outrageous suggestion, considering that three former chief ministers — Lalu Prasad, Om Prakash Chautala and Madhu Koda — have been convicted on charges of dodgy financial dealings and are in jail. This is not to mention the various other former ministers and sitting MPs who are under the scanner of the Enforcement Directorate on charges ranging from tax evasion and money laundering to bribery. In Mamata’s idea of India, all such inquiries violate democracy and, possibly, this is an idea that binds the Opposition together. No wonder many of the 23 parties hate the idea of a prime minister who not only imagines he is the chowkidar but also presumes to undertake his responsibilities with diligence and sincerity. Most normal people have got over the temporary inconveniences of demonetization and have adjusted to the ‘less cash’ economy. But these don’t include those who had to take desperate measures to save whatever they could of their secret war chests. They are worried about the past coming to haunt them and they seek both amnesty and immunity. And this has not been forthcoming.

That may explain the desperation to get rid of Narendra Modi.