The museum has changed from the days of the magic cabinet, that repository of wonders. It now connects the present with the past and future, inviting visitors to infer narratives, to see, hear, even interact with, aspects of history, science or nature through multiple modes which grow more sophisticated with technological advances. The Museum of the Word, about to be opened in February, promises a display that will offer an immersive experience of the evolution of Indian languages. Inaugurating newer dimensions in Calcutta’s cultural and educational scene, it is being set up in the Belvedere House of the National Library. Although plans for a Centre of the Word with a slightly different focus, together with a project report, had been made in 2010, the concept had lain dormant until 2020. The Museum of the Word will focus on India’s linguistic variety, drawing out through the use of projectors, graphics, virtual reality tools, interactive games and selected artefacts the many facets of language, and its impact on and response to society.

Moving from non-verbal communication through oral traditions to manuscripts, printed books and electronic texts, the museum aims to preserve the histories of languages, scripts and literature, and thus celebrate India’s plural traditions of speech and writing. It will present notable scholars, poets and writers too, which should arouse awareness of their relevance to the present, and the history of printing, the role of public libraries and the history of Belvedere House. This is not just a remarkable addition to the cultural horizon but also a symbol of hope, because it draws attention to diversity. More, its presence would neutralise the kind of fears associated with Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, in which civilisation was being destroyed by burning books. To save it, each person memorised a whole book, for only by saving the ‘word’ could human society regenerate itself. Instead, the Museum of the Word would symbolise the dynamic and multi-layered processes of civilisation.

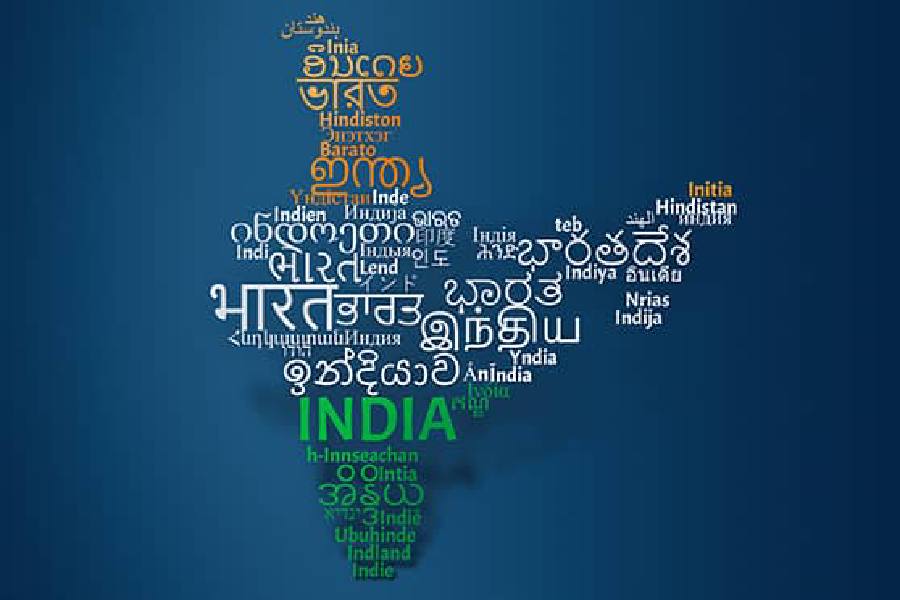

Or much of it. The museum will present the 22 official languages of India, which is a huge venture for any institution. And this is certainly an institution, and that, too, under the Union culture ministry. India’s languages have come from multiple sources and assessments of their numbers may vary from, say, 780 to 456. The 2001 census identified 122 major languages and 1599 other languages. The celebration of diversity is also an institutionalisation of India’s linguistic histories; the narrowing cannot be helped no doubt, but the result is the same. A sense of broader horizons in India’s universe of languages could be created to avoid rigidity. Speakers whose mother-tongues do not fall within the 22 represented languages, who might have felt the stress of communicating in school or at work in a tongue they were not born into, should feel at home in the museum too. For plurality also means inclusion, a welcoming into the vast world of the word.