Of course, lynch and lynching are foreign words. But lynchistan, an apposite colloquialism for parts of the cow belt, is impeccably desi. The term derives from practices that would have horrified Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi whose birth anniversary is being celebrated with opportunistic ostentation, practices which provoke little high-level censure in what we are told is India’s third golden age after the Mahabharata and Gupta eras.

A suffix or a prefix often indigenizes an alien word as I am reminded every morning by fluting calls of “Driverji!” from my Hindi-speaking neighbours. Indian society would have been even more static without this constant enrichment. However absurd the claims about ‘genetic science’ and ‘plastic surgery’ that tub-thumping politicians trot out, India’s language has always been catholic with a wonderful knack of pouncing on appropriate words anywhere in the world and applying them to things that loom large locally. It was only much later that I realized that the “ujbok” epithet my father hurled at me when I was especially clumsy as a little boy stood for Uzbek. Even later, when the erudite Nurul Hasan was West Bengal’s governor, I learnt that this was another word that the East Bengal dialect had absorbed from the courtly Persian’s disdain for the northern neighbour who gave us the Mughal dynasty. East Bengal — East Pakistan by then — also taught me that under the law a man’s wife need not be his waris (another Persian import) or heir.

The patriotic alternative of coining words hasn’t worked. No one, not even those who have no English, speaks of kanti ka langot for a necktie. Not that imported words always add to clarity. They can cause further complications when imperfectly grasped. Anna’s King of Siam flew into a rage when the Times, London, called him a “spare” man: he thought it meant redundant. An English-language daily in Tehran had to apologize to the Shah (then at the height of his power) because its gossip columnist reported that a certain worthy was “squiring” one of the princesses around. The royal court invested squiring with a far less innocuous meaning. Here, even well-placed ostensibly English-educated persons say “officious” when they mean “official”. A legendary officer gave his subordinate a glowing confidential report year after year but stymied promotion by adding “no drive”. Made aware of the contradiction, the officer explained, “I’ve been telling him to get a driving licence!”

That was nothing compared to the suffering the word “terminate” inflicts on travellers as I discovered on returning from one of my working stints in Singapore. Calcutta customs politely explained I would have to pay full duty on every purchase in Singapore because the rule book stipulated that only Indians who returned to India on the “termination” of their service abroad could claim exemption. Where was my termination certificate? My Singapore employment contract with the expiry date wouldn’t do. It didn’t have the word “terminate”. A little learning is a dangerous thing. Britain’s Prince Andrew ended his speech when he visited Calcutta some years ago with the remark, “We gave you a bureaucracy. You developed it.”

We have developed much else, including the word develop to laud a horrid process of destroying both the language and natural beauty in the name of improvement. An outstanding example of the former is the word “prepone” which rests on the illusion that “pone” is a root noun subject to pre and post. No doubt because of his stint in New Delhi, Lord Wavell wrote to Ivor Brown, editor of the Observer, suggesting “a monthly journal of words that required protection and a pillory of misused words”. George Orwell’s Newspeak, the official language of his totalitarian dystopia in Oceania, must also have owed something to his experience as an officer in the old IP, the Indian Police. His “A not unblack dog was chasing a not unsmall rabbit across a not ungrown field” was an extreme example of the meiosis grammarians associate with bureaucrats.

For all I know, “prepone”and the reinvented “officious” have earned lexicological respectability. After all, 1.3 billion Indians can’t be dismissed lightly, not because of any philosophical weightage but because several millions among them can afford American-made washing machines or are seen as a possible substitute for the European Union after Brexit becomes reality. Given this powerful commercial rationale, I was not surprised to find a huddle of Indian businessmen at an Indian high commission party in Singapore pooling their collective brains to think of a Hindi equivalent of guanxi (pronounced gwon-she) meaning “network” or “connection” in Chinese and seen as a magic mantra that opened doors for new business and facilitated deals. Someone with a lot of guanxi was obviously better able to generate business than someone who lacked it and was moreover at the mercy of officials wielding the lethal weapon of half-understood but creatively interpreted English terms. The best those enterprising traders could come up with as India’s answer to guanxi was bhai-bandh which wasn’t very catchy and sounded as contrived as kanti ka langot. So far as I know it never passed into daily use.

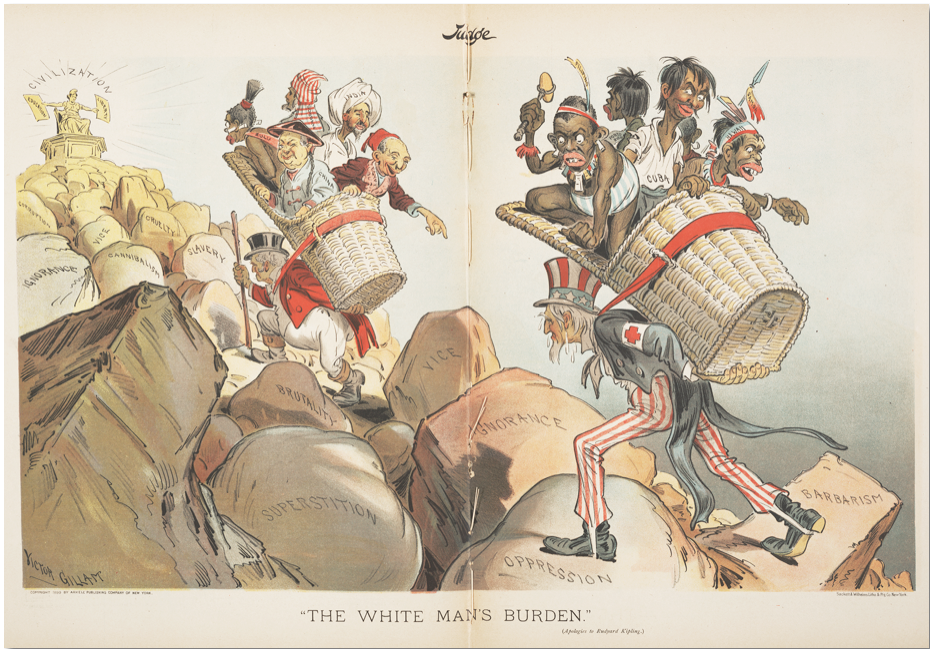

That’s the beauty of lynchistan. It is spontaneous. It reflects current reality. The traditional Hindu way of showing disapproval was a mild form of excommunication — withdrawing all essential services such as dhobi and barber. It has been replaced by a far more brutal Hindutva blend of kangaroo court and the dreaded Spanish Inquisition from medieval Europe only since the Bharatiya Janata Party’s second coming which is hailed as the third golden age of Indian history. Lynching has no roots in the Bible. But some dictionaries mention a 16th century American source, later revived against Blacks. Future lexicographers would be justified in describing it as an Indian form of mob murder of anyone who is visibly Muslim. The word might be bracketed with lathi which a teenage English girl once described in an inter-schools quiz as something the police in India use to beat people, although she had no idea of its shape or size.

If lynch and lynching are foreign, so is boycott which dates from the Irish struggle against landlords. As a nationalist Irish MP, John Dillon, put it, no violence should be used against Captain Boycott, a landowner, but “let every man’s door be closed against him; and make him feel himself a stranger and a castaway in his own neighbourhood”. That could be the benign Gandhi himself who opposed without hating but whose satyagraha added spiritual sophistication to boycott’s blunt ostracism. Despite the Gandhi Jayanti celebrations, the man himself is obviously very much an unwanted person. Otherwise, the BJP would not have wanted the country’s highest civilian honour to be bestowed on one of the people charged with conspiring to murder him. If the government doesn’t oblige the ruling party, it will be only because of the canny realization that no one outside the saffron ranks reveres murderous intent, albeit unsubstantiated by clinching evidence, as “veer”.

However, the ready applause of toadies and cronies might persuade the authorities that they need address only their own constituency of self-seeking loyalists. It simplifies communication. Sir Ernest Gowers tells of an Indian official who, on finding his British superior laboriously correcting a letter he had drafted to another Indian official, remarked, “Your honour puts yourself to much trouble correcting my English and doubtless the final letter will be much better literature; but it will go from me Mukherji to him Bannerji, and he Bannerji will understand it a great deal better as I Mukherji write it than as your honour corrects it.” If Modi understands Bhagwat and Bhagwat follows Shah, no one else need matter in lynchistan.