Future historians studying the Ayodhya dispute will be struck by a curious fact: the relative absence of any debate or discussion on the issue in the run-up to the Supreme Court’s unanimous judgment on November 9. No doubt there has been a great deal of dissection of the dispute in the aftermath of a judgment that conceded the right to build a Ram temple in his Ayodhya janmasthan, but for the nine years following the Allahabad High Court judgment of 2010 there was relative silence. It almost seemed that all the sides of the dispute had become weary of going over familiar ground and restating their positions. They simply wanted closure.

The spirited debates on the Ayodhya tussle took place in the period between the shila puja ceremonies of 1988-89 and the installation of the first National Democratic Alliance government under Atal Bihari Vajpayee in 1998. Those were heady times. In 1990, the Bharatiya Janata Party president, L.K. Advani, began his famous Somnath to Ayodhya rath yatra, promising the “greatest mass movement” in India’s history. It was not an idle boast. The spectacular response to the yatra redefined Indian politics. The BJP was catapulted from being a minor party competing with the Janata parivar and the Left for a share of the non-Congress space to becoming the alternative to the Congress. The Congress, in turn, was decimated in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh and lost its ability to secure a commanding majority in Parliament.

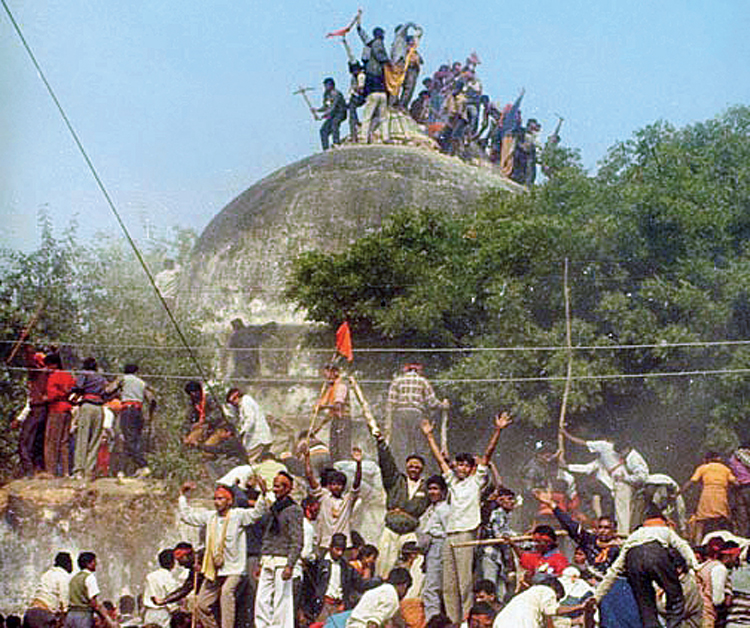

From 1989 to 1993, when it appeared —quite mistakenly — that the tide had turned, Ayodhya dominated the Indian political landscape. Hindutva entered the political vocabulary and there were passionate debates on the relationship between religion and politics. When the Babri Masjid structure was demolished on December 6, 1992, in the presence of nearly all the front-ranking leadership of the BJP, there were loud concerns over India’s drift towards fascism. The future of secularism was widely debated and political alignments were shaped along communal-secular lines. Also debated was the changing nature of the Hindu faiths and the so-called ‘semitization’ of Hinduism. The famous jurist, Nani Palkhivala, described the period as the ‘Ayodhya years’ —a phase of contemporary Indian history marked by political turbulence and intellectual ferment.

Unrelated to the Ayodhya dispute, but developments that cast their long shadows on it, were the shifts in India’s political economy. Exactly 30 years ago, in November 1989, shortly before the general election, the Rajiv Gandhi government facilitated the shilanyas for the construction of a gateway to the proposed temple to Ram. By a curious coincidence, the shilanyas happened on the very day the Berlin Wall was breached and the mighty socialist regimes came tumbling down, one by one. The Nehruvian consensus built after Independence rested on three pillars — socialism, secularism and non-alignment. They also rested on the benign gaze of the Soviet Union.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union and the abrupt end of the Cold War, the Nehruvian consensus started developing deep cracks. Confronted by a severe balance of payments crisis and the threat of imminent bankruptcy, the P.V. Narasimha Rao government changed the course of economic policy. In the budget of 1991, the then finance minister, Manmohan Singh, began the process of dismantling the licence-permit-quota raj, which, in any case, had run out of steam and stymied the country’s economic growth. Although the process of taking India out of an over-regulated, public sector-driven economy into a market-driven one was halting — and, in fact, still incomplete — the Rao government’s change of gear generated confusion in the ranks of the political class aligned with the Congress and its offshoots. The Left in particular, already shaken by the collapse of the Moscow Centre, was totally disoriented, as were the intellectuals who had been identified with the Congress-Left ecosystem.

In political terms, this had two consequences. First, there was something resembling an ideological void in the ranks of those who were loosely attached to the Nehruvian consensus. This meant that the ability of the existing political establishment to meet the Ram Mandir challenge was seriously impaired. Traditionally, the Left had provided the intellectual ammunition for confronting ‘reactionary’ forces and for which they had been rewarded with control over the centres of intellectual capital, including the academia and the media. Now the Left itself was in disarray and its defence of ‘hard’ secularism lacked the robustness of an earlier era.

Secondly, beginning with the Iranian revolution of 1979 and extending to the Afghan resistance to the Soviet occupation of the country, political Islam started becoming a global force. Read with the troubles in Punjab and the spread of Khalistani separatism, the fear that India was in danger of being torn apart became more and more real. The search for new bonds that would unite India led to voyages of discovery, some of which led to the identification with the BJP’s cultural nationalism and the symbolism of Lord Ram.

After the 1991 general election and the victory of the BJP in the UP assembly, it was pretty apparent that the Ram temple movement had captured the imagination of a substantial section of India’s Hindus. It was clear that circumstances were propelling the transformation of passively religious Hindus into assertive political Hindus. The demand for the Ram temple at the exact spot where the shrine built in the 16th century stood rekindled memories of temple destruction and brought to the fore a passionate desire to correct the wrongs of history. For many who took up cudgels for the Ram temple movement, the motivations were more political than religious — as it certainly was with Advani and much of the BJP leadership. It became an occasion for building a Hindu political community, which could cut across the caste divide of the Mandal Commission reservations that was introduced by V.P. Singh to stymie the Ram temple agitation.

There were two options available to the BJP’s opponents. First, there was the invocation to uncompromising secularism that deemed religious movements as illegitimate. By this logic, religious majoritarianism had to be firmly resisted without conceding an inch. Second, there were those in the Congress that sought to co-opt Hindu grievances and drive a wedge between it and the BJP.

In the bid to unitedly oppose the BJP, but without being seen to oppose the Ram temple, the attempt was to prevaricate. After the 1992 demolition, the thrust was to invoke the Constitution and the rule of law to delay any movement on the Ram temple. The belief was that time would be a great healer and that the BJP would suffer the consequences of its failure to secure the temple within a reasonable time. It was in this context that the buck was passed on to the judiciary to either prevaricate or thwart the project on the grounds of ‘constitutional morality’.

The approach had a modicum of success. After 1992, the judiciary showed no great enthusiasm in treating the disputes over Ayodhya as urgent. It took the Allahabad High Court some 18 years to pronounce its judgment and the Supreme Court may well have dragged its feet longer had the Chief Justice of India, Ranjan Gogoi, not decided that no further delay was acceptable.

Having shouted ‘let the courts decide’ for decades as a way of avoiding a political decision, the BJP’s opponents are no longer in a position to cry foul now that the Supreme Court has decided to bow before public sentiment. In being even-handed, it has also dubbed the demolition as a violation of the rule of law. Yet the question remains: would it have given a similar judgment had the disputed structure been intact?

The construction of the Ram temple would not have been possible without the events of December 6, 1992.