In early March, Germany announced what it described as a feminist foreign policy orientation, outlining that gender rights would be the central pillar of the country’s diplomatic priorities in the future. This declaration is in keeping with a growing pattern of nations, including France, Spain, Canada, Mongolia, Chile and Mexico, among others, committing to feminist foreign policies. What such a policy actually means on the ground is unclear. Yet, this trend poses important questions for India’s foreign policy establishment too. Some countries, such as Mongolia, have defined their approach as supportive of global initiatives to advance the empowerment of women while increasing the strength of women in their foreign service. Others, like Spain and Canada, have argued that they intend to use the lens of gender equality — and, more broadly, justice for marginalised communities — in their foreign aid disbursements and policy priorities. India, without calling its foreign policy feminist, has long supported international laws and efforts towards gender equality. New Delhi has described gender justice as a key focus of its ongoing G20 presidency. However, beyond big statements and generic commitments, India has a long way to go and many stumbling blocks to overcome.

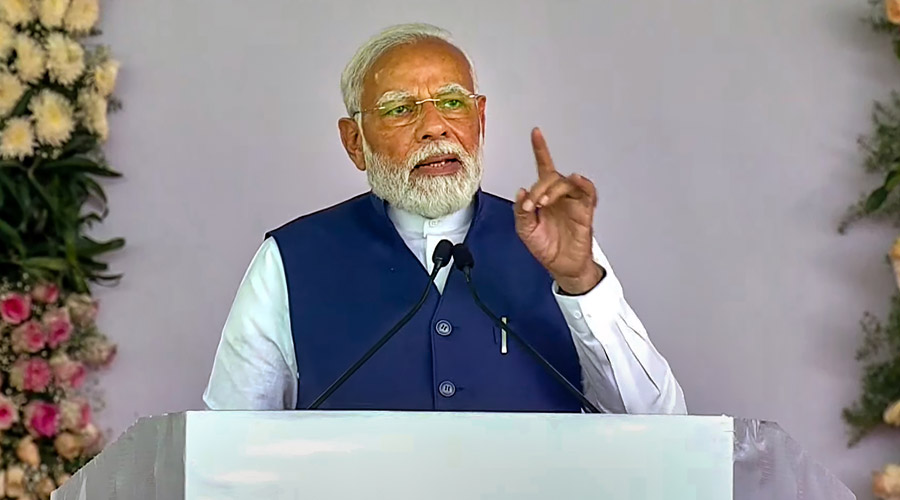

Despite efforts to diversify the Indian Foreign Service, only about a quarter of its officers are women. The fraction of women in the top echelons of the ministry of external affairs — at the headquarters and in key foreign capitals — is even smaller. India has had only three female foreign secretaries and the only woman who was a full-time foreign minister, Sushma Swaraj, enjoyed little authority in the Narendra Modi-led government, according to a book by Mike Pompeo, the former secretary of state of the United States of America. Until 1973, female IFS officers were barred from marrying. But there are even bigger contradictions at play. It is difficult to speak of women’s rights as a priority in foreign policy when India continues to support the development of a Taliban-led Afghanistan, including, reportedly, through a training programme for government officials. The Taliban has systematically withdrawn the hard-won rights of women, in education, in the workplace and beyond. India’s own track record makes it even harder for it to speak up for women globally. When men convicted of gang-raping Bilkis Bano in 2002 were released last year, the government frowned upon the diplomatic criticism it received. If justice for women does not matter at home, it never can abroad.