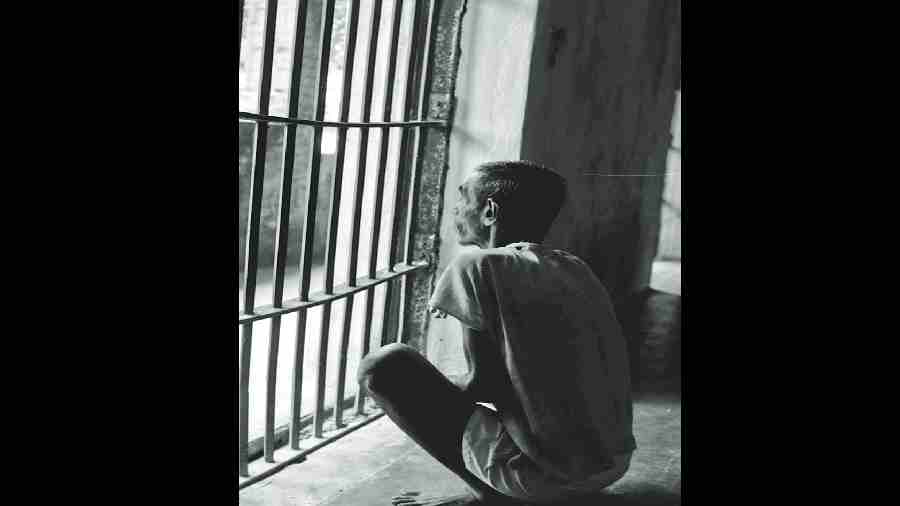

We do not — cannot — imagine life in prison. By ‘we’, I mean those who have not been in prison. Jails, we believe, are for others.

A moment’s reflection will tell us how short-sighted that is; how self-centred, wrong.

Speaking of India and Indians, the number of offences listed in the Indian Penal Code for which the punishment is imprisonment for life or for different terms, under ‘simple’ or ‘rigorous’ categories, is huge. The number and nature of enactments outside the IPC for which arrest and imprisonment are envisaged is also large. For us to have a sense of what life in jail means is eminent good sense. Exactly as it is for us to know what it feels like to be in hospital. Rightly or wrongly, for a real or wrongly-suspected condition, or just unwittingly, one could find oneself in prison.

How is one to acquire that ‘gyan’ of prison-life?

A visit would, of course, be the best method. But jails are not public spaces where one may saunter in and out. One has to have credentials to visit a jail — as I did. The then prime minister, Manmohan Singh, had advised governors to visit ‘Correctional Homes’ (as jails have very appropriately been renamed) to see if their conditions were aligned with basic human dignity and decency. Visiting the one at Alipore, Calcutta, my first and most unforgettable ‘gyan’ came from a sound — the cold and steely clang of the bolt that shut the barred prison gate behind me. I was a privileged visitor and the guards performed that duty with many salutes but I can never forget that sound which said in every language on earth: ‘You are now “inside”; the world and everything in it like loved ones’ laughter, the aromas of freedom, the taste of options, the invitation to do as you please, is now “outside”.

The detenus, undertrials and convicts I met in different Correctional Homes were interested, of course, in improvements in their conditions. One of them, as I was leaving the one in Alipore, came running to me with what I thought must be a mundane complaint. It was not. He asked me if the prison library could not get a better range of books. Chastened, I told myself, that is Bengal. Bankim’s, Rabindranath’s, Sarat’s, Mahasweta’s Bengal. And I was not surprised to see that ‘prison reform’ in the state of West Bengal had gone to the extent of getting prisoners to take part in staging Tagore’s plays, a production of Tasher Desh travelling to Delhi and being staged in the capital’s Siri Fort auditorium.

But while every inmate of a jail would want better books, better food, better treatment, what she or he really craves for is to be out, to be released, to get mukti. And that is what a convict just cannot get, pre-term. An under-trial, however, can, if qualified for it under a provision introduced in the Criminal Procedure Code — Section 436A — by an ordinance in 2005. This basically says that if any prisoner being tried, in other words, an under-trial prisoner, a ‘UTP’, for an offence not punishable by death has undergone detention up to one-half of the maximum period of imprisonment specified for that offence, that under-trial prisoner shall be released by the court on a personal bond with or without sureties. And, further, that no under-trial prisoner shall be detained for more than the maximum period provided for that offence.

Section 436A is an extraordinarily mitigative instrument in the hands of the justice system. It is a sagacious provision that humanizes penology, sends a beam of hope into the grey dank of a prison cell.

As on 1.1.2021, there were 3,71,848 UTPs in India’s 36 states and Union territories, amounting to more than 75 per cent of the total number of human beings in Indian prisons. The numbers today are unlikely to be very different. Of these, those ‘eligible’ for ‘premature’ release under the ‘one-half of the maximum period of imprisonment’ is very small. Those actually released, even smaller.

The ‘beam’ of hope is slender and weak. The intention behind the 2005 ordinance has not been served. Where is the snag? It is for state governments, being in charge of prisons, to act on S.436A in their wisdom. But there has to be such a thing as a national propulsion for action for implementing the spirit of the new Section. Is that propulsion there? Are punitive instincts stronger than human ones?

On this Amrit Mahotsav of India’s freedom, a re-look at the scope of S.436A would be apposite. I would urge that ‘one-half of the maximum period’ be modified by a new yardstick to the advantage of the UTPs. And advisories be issued to state governments to ensure that not a single UTP eligible for ‘premature’ release is denied that release. S.436A is meant to be celebrated, not deflated, activated, not frustrated.

This is also the occasion to celebrate another exceptional arrangement pertaining to prisoners. In 2008, India and Pakistan agreed to exchange lists twice every year, on January 1 and July 1, of civilian prisoners in each other’s custody. This came from the fourth round of ‘composite dialogues’ then in progress between the two governments. The late Pranab Mukherjee was our minister for external affairs then and his Pakistani counterpart was Shah Mahmood Qureshi. Our then high commissioner to Pakistan, the late and absolutely brilliant Satyabrata Pal, signed the agreement for India while the then Pakistan high commissioner to India, Shahid Malik, signed for his country.

The exchange of lists has been happening regularly despite all the fluctuations in our bilateral ties, including the deep lows caused by terrorism. On January 1, this year, India and Pakistan exchanged, through diplomatic channels simultaneously at New Delhi and Islamabad, the lists of civilian prisoners and fishermen in their custody under the provisions of the 2008 Agreement. India handed over a list of 282 Pakistan civilian prisoners and 73 fishermen in India’s custody to Pakistan and Pakistan shared a list of 51 civilian prisoners and 577 fishermen in its custody who are Indians or are believed to be Indians. The next exchange is due on July 1.

The assumption of office by a new government in Pakistan coinciding with the 75th anniversary of Independence in both countries gives them an opportunity to infuse a new energy into this essentially humanitarian situation and exchange more than lists — exchange prisoners. And, withal, in the course of this salutary process, vouchsafe the long overdue return to India of Kulbhushan Jadhav.

Going a step further, a similar exercise done between India and Bangladesh as well would make the Amrit Mahotsav live up to its name.

Age-senior readers of this column will recall the 1961 Hindi film, Kabuliwala, based on Tagore’s great story (1892) of that name. Manna Dey sings hauntingly in it Prem Dhawan’s song — “Ay mere pyare watan... Ay mere bichhare chaman...” — for Balraj Sahni. The India-Pakistan Agreement of 2008 is the diplomatic embodiment of that arazu, that abaru. It must come alive this year.