The recently broadcast first part of India: The Modi Question, BBC’s documentary on Narendra Modi and the Gujarat killings of 2002, makes for curious viewing. For any Indian engaging with the news since 2002, much of the material is familiar, the ground the film explores over 58 minutes mostly well-trodden.

While the documentary goes back and forth to reveal them, the events laid out in the film are also well-etched in our minds — sequentially: the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh is formed in 1925 as a Hindu supremacist organisation aping Italian fascists and Nazis; the RSS likes to recruit boys from a young age; Modi is one such boy who is recruited; Modi rises in the RSS and is taken into the Bharatiya Janata Party, the electoral arm of the RSS; the 9/11 attack creates an open season on Muslims the world over; Modi takes over as Gujarat’s chief minister in late 2001; from early 2002, trains between Gujarat and Ayodhya start ferrying Hindutva kar sevaks for the Ram mandir agitation; one such train carrying a mix of pilgrims and returning kar sevaks is stopped near Godhra on February 27 and four of its carriages are set alight; 59 people, including women and children, all Hindus, burn to death in carriage S-6; a mob of local Muslims is blamed for this; within a startlingly few hours of the Godhra burning, widespread attacks begin on Muslims all over Gujarat; though the violence continues for months, the most intense bit of it takes place over the next three days, especially in Ahmedabad.

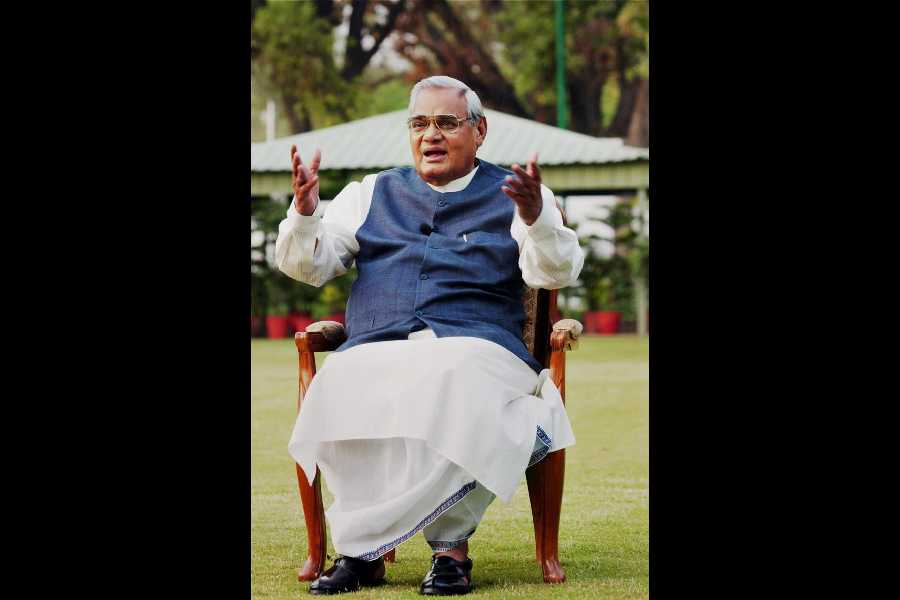

After this, questions about the responsibility for the murders and rapes start to circulate. The documentary details some of the following: why did the chief minister fail to stop the violence? Was he simply incompetent and unequal to the challenge? Did he deliberately ask the police to stand by and let the grotesque retaliation take place? Was it, indeed, a retaliation or was the initial Godhra attack also part of a wellthought-out plan to unleash the pogrom on Muslims? Whatever the case, why was the delivery of justice so sparse and tardy in the aftermath? Why were first information reports and investigations so widely and deliberately hobbled by the authorities? Why did the former prime minister, A.B. Vajpayee, and the former home minister, L.K. Advani, fail to act in the face of this mass atrocity? Why did they let Modi not only continue to be in charge but also call for state elections shortly afterwards? Who killed Haren Pandya, the former minister who was openly critical of Modi? Did the SIT constituted in 2008 to investigate the violence do its job properly?

In the documentary, a few new things stand out from the mass of familiar material. Soon after the killings, the British government sent a team to investigate what had happened in Gujarat. The film has accessed the team’s report — one that was never made public — and it clearly states that Modi was directly responsible for the killings and other violence that took place. Jack Straw, who was British foreign minister at the time and someone who clearly read that report, comes on camera to hum and haw and say that while they knew about Modi’s culpability, there was no way they could have broken diplomatic relations with India; another high official in the British government (who remains anonymous) says he regrets they didn’t do more to bring Modi to book internationally but that they did what they could. The film also mentions that the European Union had sent a separate team to investigate Gujarat and that the United States of America also imposed a travel ban on Modi, and that the travel bans by the United Kingdom and the US were only lifted once Modi became prime minister.

This first part of India: The Modi Question revisits events and material with which we in India are well acquainted. But the question it singularly fails to ask is what were the Western leaders in possession of such detailed reports doing jollying along with a person their reports named as a major violator of human rights? The people who become implicated by this film are David Cameron, Theresa May, Boris Johnson and Rishi Sunak; the tough questions an Indian might want to ask might be to Barack Obama and Donald Trump, to various European leaders, especially the Rafale-vending François Hollande and Emmanuel Macron.

As to the response to the film by the Government of India, it comes as no surprise. In the film, there are a couple of bits of TV footage, nuggets from the time when Modi actually agreed to face an interviewer’s camera and hostile questions soon after the 2002 violence. In one, when the BBC correspondent asks him about human rights violations, he snaps at her that he doesn’t need any lessons in human rights from a Britisher. Risibly and shamefully, Arindam Bagchi, spokesperson of the ministry of external affairs, continues to parrot his master’s voice when he says this documentary pushes a discredited narrative and shows a “continuing colonial mindset”. Just as any criticism of actions by the Israeli State is now labelled anti-Semitic by Benjamin Netanyahu’s defenders, any questioning of Modi or the sangh parivar, even by reputed Western media, is labelled ‘colonial’ by the inheritors of the raj-toadies who did precious little to remove colonialism from India.

The blocking of the film in this country is also of a piece with how Modi sees democracy and the free press. In the same interview, the BBC interviewer, unruffled despite Modi’s aggressive responses, asks him if he thinks there is something he could have done better to respond to the bloodbath that had just exploded under his watch. Modi stares at the interviewer for a beat and, then, without bothering to mask the menace, answers candidly: “Yes, one area where I was very weak — how to handle the media.”

We are told that one reason why Mr Modi won’t give unscripted interviews to foreign media is that his English is not good and he would be risking misinterpretation. Upon this evidence, that can be added to the long list of untruths that provides an entourage to his persona. Mr Modi’s English is more than adequate; he just can’t afford to be so candid. Be that as it may, ban or no ban, he and his advisers should be aware that every leader he meets during India’s G20 presidency will be sure to have seen this film.