In October, a group of Italian artists were arrested in Ahmedabad for ‘defacing’ metro coaches by a police squad tasked with combating terror-related crimes. A police press release stated that when the group was interrogated, “it was found that there is a craze of drawing such graffiti in Europe and America,” and that “the individuals arrested are also addicted to graffiti-aerosol painting.” The police also added that “graffiti spray bottles of different colours and bottle caps have been seized from the accused for further investigation.” Yes, you read that correctly.

The arrested Italian artists have been accused of violating several sections of the Indian Penal Code — Section 447, which deals with criminal trespassing, Section 427, which deals with mischief causing damage to the amount of fifty rupees or more, Section 34, which deals with acts done by several people in furtherance of a common intention, and Section 3(1) of the Prevention of Damage to Public Property Act. The artists face a maximum sentence of seven years and three months in prison. Notably, in addition to this case, the group of artists has been accused in four other cases registered with the police in various states across the country.

The police’s actions demonstrate how law-enforcement officials, whose job it is to prevent crime, can weaponise existing legislations to target artists. The police’s conduct suggests that they consider the actions of these artists to be vandalism. The police have also insisted on filing a criminal case against them in order to paint a picture of an ‘organised nexus’ of graffiti artists. This is where the police are wrong.

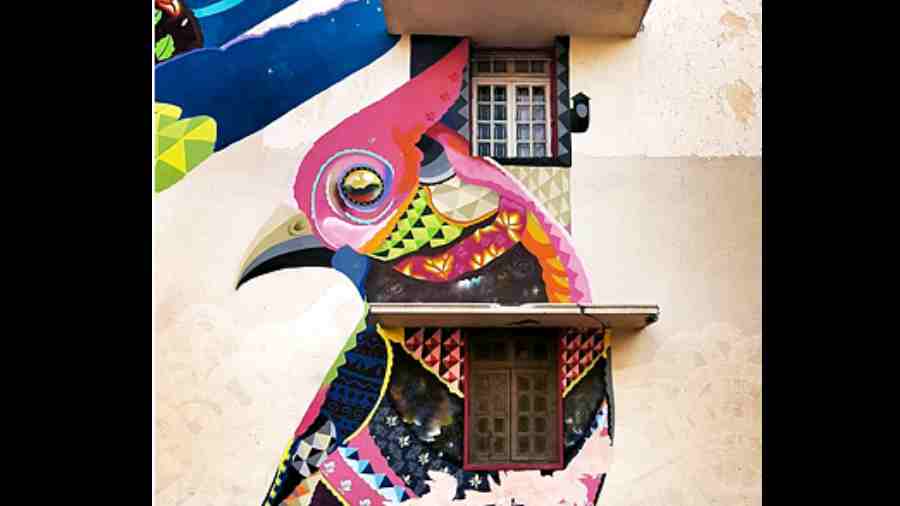

Some people may find graffiti in public places repulsive. But it is important — and appropriate — to remember that graffiti painting, like other forms of art, should be regarded as a form of expression. When one looks at public spaces around the world, one realises that graffiti is an important part of a city’s culture. The significance of this type of artwork is perhaps reflected in the fact that similar works have found space in iconic art galleries and museums, including the Tate Modern and the Guggenheim.

While graffiti has left an indelible mark on cities, authorities have not always been accepting of this form ofart. For instance, authorities in some cities in the United States of America, including New York and Portland, have been intolerant of graffiti and have sought to remove and penalise graffiti painting in public and private spaces. Other cities, including Berlin, Melbourne, and Miami, have been supportive of graffiti in public spaces, albeit with varying degrees of regulation. The latter are positive examples from which we should draw inspiration. The key here is for authorities to develop effective and proportionate regulations that allow artists to find spaces to express themselves in cities.

Closer to home, the creation of open art spaces like the Lodhi Art District is an example of how authorities have successfully supported artists’ creativity. The LAD is India’s first public art district, located in New Delhi, and is spearheaded by St+art India Foundation. The initiative has seen the organization support collaborations between artists both within and outside the country with the help of embassies and brands. The movement in support of art in public spaces appears to be growing as we have seen more such instances in Mumbai, Hyderabad, and Goa. The immediate result, of course, is that these initiatives make our cities look better and attract tourism. It is critical that authorities continue to support these initiatives and work with artists on these projects rather than subjecting them to criminal trials that limit their freedom of expression.

Jade Lyngdoh is a Meta India Tech Scholar (2021- 22) at the National Law University, Jodhpur