Germans have a word for transformative change — zeitenwende. Of late, it’s frequently used in relation to the Arab world which is witnessing a quiet but potentially seismic cultural and political shift. It’s happening at two levels. One is the process of a semblance of democratisation and modernisation in Gulf countries and, significantly, in arch-conservative Saudi Arabia. The other area is international relations which until recently were defined by the Arab world’s dependence on the West and hostility towards Israel. That’s changing amid moves towards greater ‘strategic autonomy’ vis-à-vis the West and — controversially — closer relations with Israel.

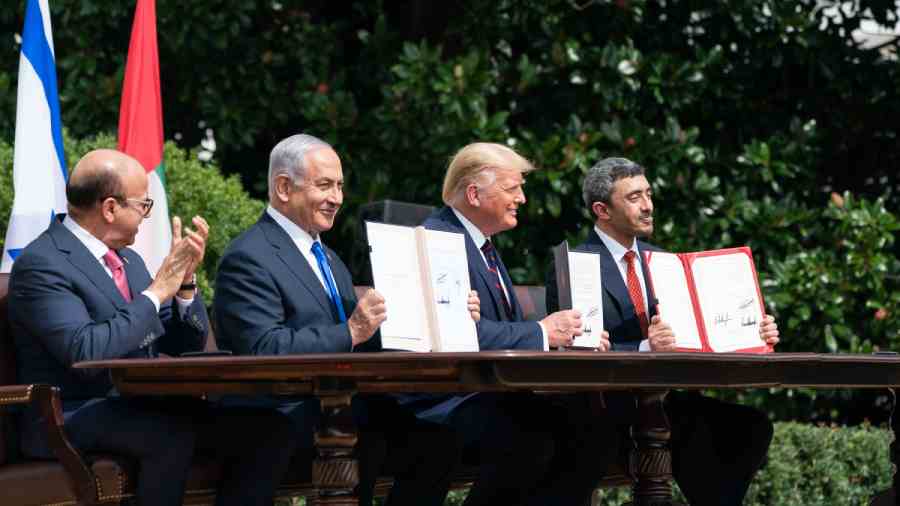

Unsurprisingly, there has been resistance. Conservatives are protesting against cultural and social reforms; Left-liberal progressives are railing against moves to normalise ties with Israel. International attention is, of course, focused on the reconfiguration of Arab-Israel relations under the Abraham Accords brokered by the Donald Trump administration in 2020. Although Trump and Benjamin Netanyahu are no longer in power, the Accords have gained wider currency. The ruling dispensations in Washington and Jerusalem continue to promote it.

Touted as a landmark breakthrough in Arab-Israel relations, the main plank of the Abraham Accords is a pledge by Israel to stop further annexation of Palestinian territory. It started off as a tripartite agreement among Israel, the United Arab Emirates, and Bahrain but over the past year and a half a number of other countries, including Morocco and Sudan, expressed interest in joining it. Naftali Bennett’s visit to the UAE last December — the first by an Israeli leader — to mark the Accord’s first anniversary was hailed as a reflection of Israel’s commitment to reach out to its Arab neighbours.

Saudi Arabia, however, is still sitting on the fence, arguing that the agreement ignores the Palestinian issue. But it is under enormous pressure from America and its neighbours to take the plunge. The fact that the Saudis have not explicitly expressed opposition to the agreement is seen as a signal that they are simply waiting for a suitable diplomatic fudge that would allow them to capitulate without being seen to betray the Palestinians. The favourable Arab response to Trump’s ‘peace plan’ and the momentum it has gained in a relatively short period have surprised observers given the initial hostility to it. It was widely seen as an attempt to legitimise Israel’s occupation of Palestinian territory. As The New York Times noted at the time, it amounted to giving “Israel most of what it has sought over decades of conflict while offering the Palestinians the possibility of a state with limited sovereignty.” The present momentum is despite the fact that Israel has not kept its side of the bargain, with no letup either in its policy of annexation of Palestinian territory or harsh restrictions on their right to freedom of movement.

Meanwhile, the Israeli– Palestinian peace process remains stalled with the prospect of a two-State solution receding further with each passing day. The fact that this has not dimmed Arab enthusiasm for the Accords confirms the increasing marginalisation of the Palestinian issue in the Arab agenda.

What should one make of what’s happening? Arab capitulation? A pragmatic attempt at acknowledging a hard reality? It’s easy to see where the critics are coming from but the truth is that the Arabs don’t have the luxury of too many options. The history of the past 74 years has shown that not talking to Israel hasn’t worked. If anything, it has made Israel more belligerent and, in turn, fed the Hamas’s militancy.

Taking a punt on a new approach makes sense even if the optics don’t look good. A new relationship based on mutual economic and security interests and not hobbled by a historically intractable problem may create a climate that is conducive for meaningful dialogue over the Palestinian issue. It’s a big leap of faith, but when the situation is as hopeless as it is, one could do worse by not exploring a way out.