The Mauritian government’s public thanks to India for its support over the Chagos Islands dispute only underlines the anguish of a tiny community that has been kicked around from pillar to post for three centuries. It also recalls an encounter in Calcutta’s Raj Bhavan with Sir Anerood Jugnauth who was prime minister of Mauritius in 1991.

Although always at the heart of the intrigue and the skullduggery associated with governing, Raj Bhavans were still genteel retreats. Governors were bhadraloks presiding over civilised society. But the tentacles of Indian reality, and a foretaste of vulgarity, were creeping in when Bengal’s governor, T.V. Rajeswar, invited a few men — I don’t recall any women — to dine with the visiting Mauritian prime minister. Rajeswar was a brisk former head of the Intelligence Bureau, concerned over Bangladeshi immigration and very different from governors like the discursive Shanti Swaroop Dhavan or the eminently refined Saiyid Nurul Hasan. Having lorded it in Gangtok’s ‘Burra Kothi’, as the old Residency which had become Raj Bhavan was popularly called, he was familiar with my name and work.

We were waiting for dinner when the telephone called him away. Before leaving, he ordered me to sit by the prime minister and talk to him. Jugnauth seemed welcoming enough, especially on learning that I knew his predecessor, Sir Seewoosagur Ramgoolam, from British Labour Party conferences where he was a fixture on first name terms with Harold Wilson. But the academic and legal luminaries among Rajeswar’s guests did not hide their displeasure. “He should have asked you …” one told another loudly enough for the whole room to hear. “No. no,” the man addressed protested modestly, “you are senior…”. Vice-chancellors deferred to barristers. Barristers couldn’t supersede high court judges. Judges insisted on yielding precedence to ministers.

What they all agreed on was that Intelligence wasn’t intelligent. “What does a policeman know of protocol?” summed up the consensus. Luckily, they didn’t know that Jugnauth’s deputy back in Mauritius was named Boodhoo. Luckily, too, Bhojpuri being his mother tongue, he didn’t understand the muttering in Bengali that erupted as I took the coveted seat beside Jugnauth.

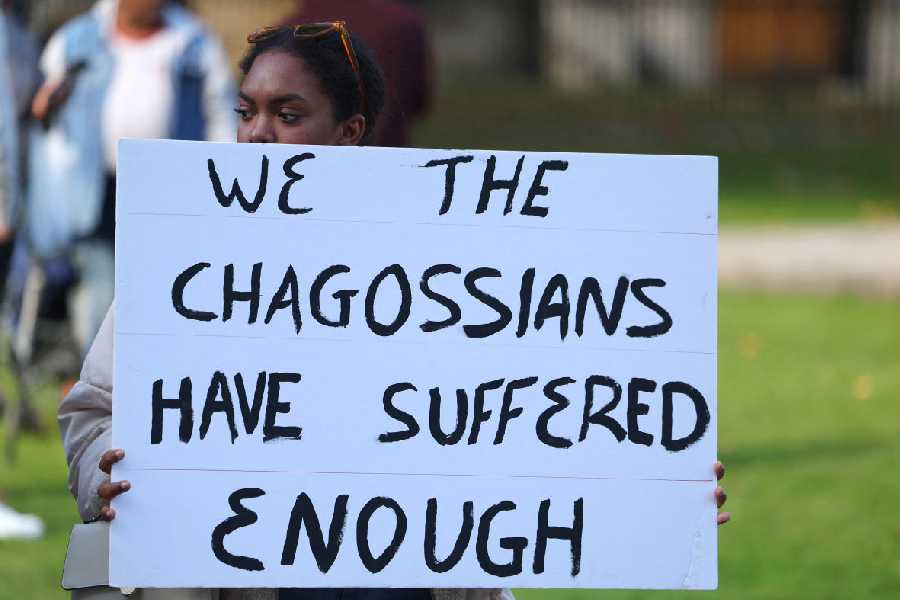

Few appreciated the real tragedy of Britain’s sleight of hand in the Sixties. While Afro-Asians frothed and fumed over American bombers thundering across the seas from their Diego Garcia base on the largest Chagos island, and Americans gloated about upstaging the Soviets to bring democracy to the Indian Ocean, Britain forcibly uprooted and expelled 2,000 Chagossians. They were forbidden ever to return home. ‘Home’ is a mythic entity for these Creole-speaking Indo-Africans whose ancestors the French enslaved in the 1700s to work Mauritian plantations. Home is still a chimera for sad groups of their descendants demonstrating outside Britain’s Houses of Parliament with handwritten posters reading “We Chagossians have suffered enough” and “We demand to be part of the negotiations.” They represent the 10,000 homeless Chagossians scattered in Mauritius, the Seychelles and Britain.

No one suspects a blow for decolonisation in Britain’s Labour prime minister, Sir Keir Starmer, gifting the islands to Mauritius more than 1,000 miles away. It is more likely an act of obeisance to Joe Biden who had warned that the ‘special relationship’ with the 51st US state would be jeopardised if bolshie Third World judges of the International Court of Justice passed a binding ruling upholding Mauritian sovereignty over the Chagos Islands. The existing ruling to that effect is non-binding. Making it binding would set the Chinese cat among nonaligned pigeons, ruling out rendition flights for Guantanamo Bay detainees, American bombing raids into Syria and Iraq, and — above all — intervention in Israel’s massacre of Palestinians. Rushed through before pending elections in Mauritius and America change the political landscape, and given China’s close ties with Mauritius, the gift might also expose the world’s largest marine protection zone to Chinese militarism or rapacity. But Tory fears of Gibraltar or the Falklands also being given away are absurd since the United States of America doesn’t wish to oblige Spain or Argentina.

The past is riddled with hole-in-the-corner deals. France ceded Mauritius and its dependencies to Britain in 1814 and Britain followed with a complex series of manoeuvres of dubious morality. The Chagos were separated from Mauritius; then, Britain paid £3 million to Mauritius (a self-governing colony by then) to buy up the entire archipelago and rename it ‘British Indian Ocean Territory’. Mauritians can’t have enjoyed selling what they regarded as their property since they claimed the archipelago as soon as they became independent in 1968. It was too late by then. Britain had already signed, sealed and delivered another agreement transferring the BIOT to the US military. To make doubly sure, Britain also bought the Seychellois Chagos Agalega Company, which owned all the BIOT islands, lock, stock and barrel, for £660,000.

In a way the Raj Bhavan encounter with Jugnauth could be traced back to Dhavan telephoning me one day when we both lived in London, he as a high commissioner and I as a newspaperman, to suggest a meeting. Intrigued, I reciprocated by inviting him to lunch. When his secretary called the next day to inquire about the venue, I asked if the National Liberal Club, of which I was a member, was acceptable. “Very acceptable” bubbled the secretary, “Sir C.P. died there!” That was news to me. Later I learnt that Sir C.P. Ramaswami Aiyar had indeed had a sudden stroke and died at my old club. He was the controversial dewan who is remembered today not for his modernising reforms but for seeking independence for Travancore.

The lunch was convivial. Dhavan was ebullient. He accepted a second bottle of hock, calling it “only flavoured water” to play down the alcohol content, and flirted with avuncular propriety with the waitress. He came to Calcutta as governor shortly afterwards and returned my hospitality many times over. On one occasion, he dragged me down after lunch to a film show in the Raj Bhavan durbar hall and then, after a while, rose and explained to the organisers, including General Jagjit Singh Aurora, the hero of the Bangladesh war, that he had another engagement but I would remain as his representative. There were no mutterings in Bengali but I wondered several years later if a precedent had been set.

That was when Nurul Hasan conducted my wife and me across a Raj Bhavan salon to talk to “Her Royal Highness”. Thailand’s Maha Chakri Princess Sirindhorn stood

up politely at our approach. Not so the two high-ranking Bengali women, wives of the state’s highest dignitaries, who sat on either side of her without uttering a word. They continued to sit in complacent silence while the three of us stood chatting until dinner was served. The governor’s concern when I returned from a year’s assignment at Honolulu’s East-West Centre to find my editorship gone was that the many more columns I would have to write to make ends meet would take toll of quality. To avoid that he had lined up a number of routine jobs that would earn me enough to write selectively. Sadly, Nurul Hasan was dead before his magnanimity could materialise.

His Raj Bhavan was an epicure’s delight. Respecting the number of mandatory courses in the Western soup, fish, meat and pudding menu, he Indianised and expanded each course, making it a meal in itself. It was a saddening breach of faith for him when a new Raj Bhavan baker turned out to be a fraud who bought readymade pastry from a confectioner. Nurul Hasan would have seen Starmer’s gift to Mauritius as a mocking caricature of the statesmanship that another Labour politician, Clement Attlee, demonstrated in India in 1947. Only Jugnauth’s son, Pravind, Mauritius’s current prime minister, is delighted with an act that will keep the Chagossians homeless for another 99 years so that the American military can operate from Diego Garcia in an increasingly turbulent West Asia.