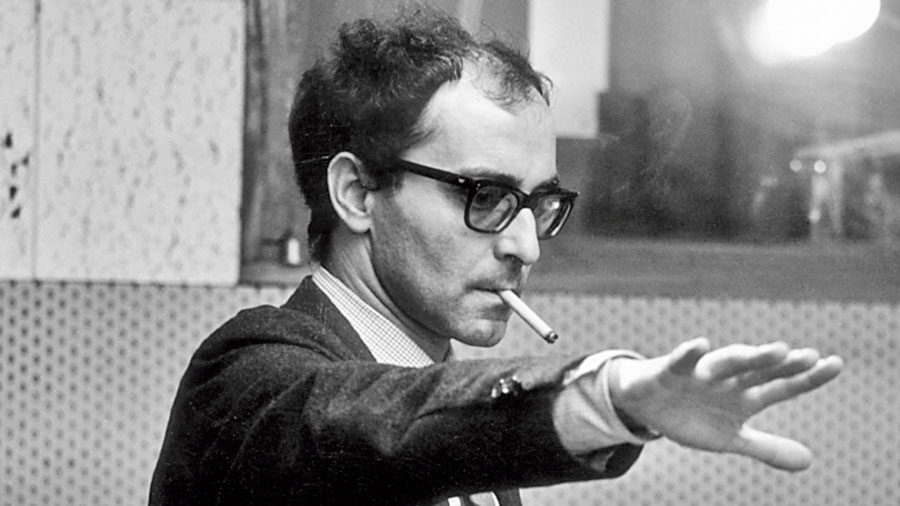

The name of Jean-Luc Godard is bandied about a lot when people discuss serious cinema. Godard as a self-indulgent director of a whole bunch of unwatchable, plotless films, or as a master, the Picasso of cinema, who smashed cinematic language and put together a new syntax that radically changed the way we make and look at films. The irascible 90-year-old recluse skulking around in his Swiss village would probably shrug at both descriptions; and neither opinion should come in the way of a re-examination of a complex and varied body of work.

I myself have always loved Godard, if always with a certain Godardian irreverence, and I recently found myself clicking on a link to view an old favourite, Masculin Féminin. JLG burst upon the international scene with Breathless in 1960. Over the next decade, he gunned out something like twenty films. The early films, from Breathless to Week-end in 1967, are broadly accepted as being JLG’s great first period and M/F is the eleventh, made at the height of what we could now call Godard v.1.0. Most of the films from this phase were in black and white, centred around Paris or some other Gallic city, made almost on the fly, often coming pretty close to a documentary shoot, the camera often hand-held, with a small cast and crew. As in many other films of this first phase, a lot of the action in M/F takes place in small apartments, cafes, bars, amusement arcades and, of course, the streets. From all reports, the ‘script’, such as it was, consisted of notes and drawings Godard made in his notebooks, sometimes even on the night before the next day’s shoot. The filming was done in the winter of ’65-’66.

Masculin Féminin — 15 faits précis (Masculine Feminine — 15 precise events), to give it its full title, starts by pretending it’s a love story. However, this is Godard, the master of narrative feints, and within five minutes the film starts pulling the rug from under the romantic tale and from you, the viewer. A young man, Paul (played by the luminously pale Jean-Pierre Léaud) sits in a cafe, awkwardly chatting up a beautiful young woman, Madeleine (Chantal Goya). They discuss jobs, labour (“the worker isn’t his own man anymore”), and the magazine where Madeleine works while she tries to make it as a pop singer. Madeleine asks a question. There’s a cut. The soundtrack is taken over by a nasty argument from an adjacent table where we see a couple sitting with a small boy. The man grabs the child and walks out of the cafe. The woman screams in helplessness as she tries to stop him. She runs to their table, fumbles in her purse and comes running back to the exit. She opens the door, small gun in her hand, and shoots the man.

For the rest of the film, we follow Paul and Madeleine but with filmic detours. From different angles we explore ideas of love, of relationships between men and women, of marriage and cohabitation, all in the context of a deeply alienating environment, with the ongoing war in Vietnam as one inescapable backdrop, with dynamics of race as another, with the atomizing, dehumanizing nature of technology as a third. If the first scene encapsulates the whole arc of a love story, from the first fumbling courtship to the terminally violent end of a partnership, the remainder of the film expands and explores various aspects of masculinity and femininity in a modern context.

As with any work that is more than half-a-century old, some aspects will appear more dated than others. Watching the mini-dramas of this group of twenty-somethings play out in the bleak, wintertime Paris of the mid-60s, what is startling is how much of the ‘story’ is still relevant today, and how utterly fresh the form of this grainy black-and-white film still feels.

When Paul goes into a booth and records a beseeching message for Madeleine on a vinyl disc, it presages the inarticulate frustrations, the cringe-making banalities we now trip into with text and voice messages. When a character says to another, “In the near future, each citizen could well be wearing an electrical apparatus designed to stimulate pleasure and sexual gratification,” or, “[g]ive us this day, a TV and car, but deliver us from freedom”. We realize we are watching one of the earliest allusions to realities and ways of thinking that are commonplace today.

For all its postmodernist elan, there are quaint details you can’t help notice; for instance, lovers addressing each other with a formal ‘vous’ (aap) as opposed to ‘tu’ (tu/tum) even in the most intimate situations. With the intervening decades helping you to pull back, you also see the macro view: Godard and the French New Wave of the late 50s and 60s are totally embedded in a particular historic moment. This kind of film-making was only possible in western Europe for a short period of time, during a time and a situation of abundance at multiple levels, where a producer would back a director like Godard to go ahead and make what he wanted, how he wanted; the plenitude involved was not just financial but also intellectual, where the freedom to explore form was consistently extended to various maverick auteurs, almost like a publisher providing an advance for an experimental book that might well fail. M/F could only have been made when it was made and where it was made. And, yet, in its prescience and pessimism, the film depicts some things that seem unchanging, as when an activist friend asks Paul to sign a letter saying, “the undersigned are deeply concerned at the imprisonment of eight members of the world of arts and letters in Rio de Janeiro for expressing their disagreement with official policy, and protest against this violation of freedom of thought in Brazil and demand the liberation of the eight prisoners.” Paul signs and asks, “Last week it was Madrid. What next?” “Athens, Baghdad, Lisbon...” comes the reply.