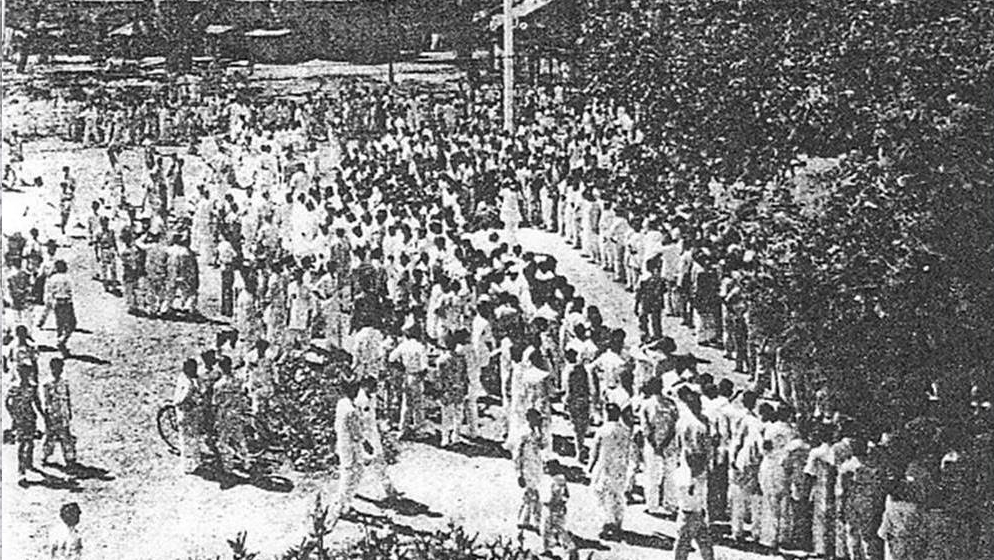

“Amar bhaier rokte rangano/Ekushey February/Ami ki bhulite pari?… Coloured with the blood of my brother/Arrives every 21st of February/ How can I ever erase that memory? How can I ever erase that memory?” Long before this date came to be International Mother Language Day, it was commemorated as Bhasha Andolan Dibos in Bangladesh. The above lines are in memory of the students gunned down by police on February 21, 1952. Students protesting the announcement that Urdu was to be the national language of Pakistan, overlooking 44 million of its 78 million people living in East Pakistan and speaking a different tongue. That day, when Gaffar Choudhury saw the body of a student protester, his head blown off, those anguished lines came to him. In the years that followed, those lines became the anthem of Bhasha Andolan legatees.

The chant

The word ekushe, ikkis or twenty one, shorn of some month before some circa after naturally throbs with the suggestion of coming of age. The violence of the State against its very own, fighting for their mother tongue, did not begin on February 21, 1952; neither did it end that day. In 1956, when the first constitution of Pakistan was enacted, alongside Urdu, Bengali too was adopted as the official language of Pakistan. Bangladesh was not born until two decades later. Today, Bangladesh has an Ekushey book fair. The nation’s highest civilian award is known as the Ekushey Padak. There is a private television channel by that name. There is something called the Ekushey Bangla Keyboard. Ekushey has gone from being a date to an incantation to a watchword for revolution to identity to triumph to credo.

Abol Tabol

For a section of people in Bengal too Ekushey has always been special, umbilical. But right now, right here, it is all about ekush. The BJP has been sloganeering for a while now “Unishe Half, Ekushe Saaf”. The Left parties are thrilled with their “Ekushe Ram. Ponchishe Baam”. The TMC too has its own ekush connection, but for now it is all focused on Mission Ekush, Assembly polls. To the man on the street, 21 is just another number, though it might remind some of a nonsense rhyme from the early 20th century. The rhyme is about a topsy-turvy world wherein no one ever knows what is going to invite the State and its ruler's ire. All that one can be sure of is that the punishments will be bizarre and for sure in sets of 21. The English translation of the poem goes thus,

In Shiva's homeland, the rules are quite strange, as I can truly attest…

While walking the streets, your steps cannot wander,

a step left or right and the king is called yonder…

Sukumar Ray called it Ekushe Ain or The Rule of 21. Touche.