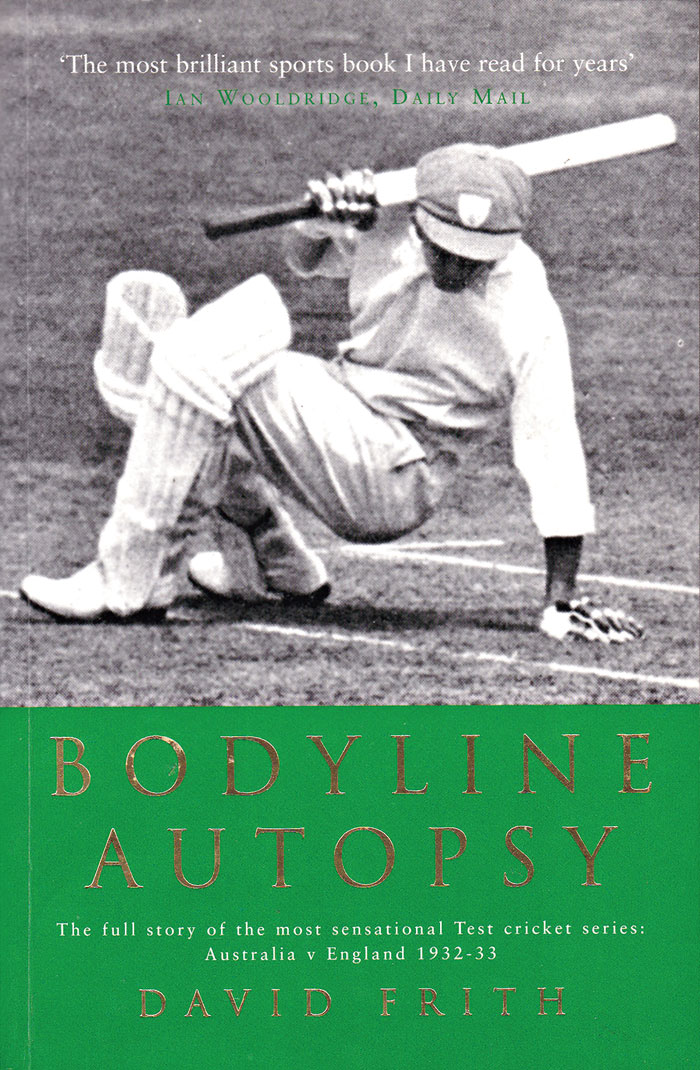

Near my home are two shops which sell second-hand books for as little as 50 pence. Although I have been instructed by family members not to buy any more books, I could not help but come away with five. The one that has turned out to be an uncannily timely read — in view of the injury caused to the Australian batsman, Steve Smith, by the “frightening” English fast bowler, Jofra Archer — is David Frith’s brilliant paperback from 2003, Bodyline Autopsy — The full story of the most sensational Test cricket series: Australia v England 1932-33.

To be sure, Archer was not trying deliberately to inflict physical harm on Smith, unlike the manner in which Douglas Jardine deployed Harold Larwood in an effort to neutralise the prolific Donald Bradman. The cover picture is of Sir Don taking “evasive action”.

Smith was hailed as “the new Bradman” after scoring two centuries against England in the first Test at Edgbaston. “How do we get him out?” wondered English cricket commentators. Now, they have discovered how, with Smith knocked out of the third Test at Headingley with a “concussion”. There is a psychological war going on with an implied threat that the ‘fast and furious’ Archer, born in Barbados but fast-tracked into the England side, will be unleashed to strike further terror among the Australian ranks.

But Archer could be the sacrificial lamb if things go wrong — as was the case with Larwood nearly 90 years ago. The fatal injury to the Australian batsman, Phillip Hughes, barely five years ago is all too fresh in the minds of Australians.

Book cover Source: Amit Roy

The past returns

On one occasion, I had asked Mansur Ali Khan “Tiger” Pataudi why his father, the eighth nawab, Iftikhar Ali Khan Pataudi, was dropped by Douglas Jardine after only two Tests during the Bodyline series in spite of the fact that he had scored a century on debut. “He scored too slowly,” Tiger replied (half-jokingly, I think).

In his book, David Frith describes “Pat”, then only 22, as a “conscientious objector” who had disapproved of Douglas Jardine’s tactics against Bradman. When Harold Larwood hit the Australian captain, Bill Woodfull, in the heart in the third Test at the Adelaide Oval, Jardine shouted, “Well bowled, Harold!” for the benefit of Bradman at the non-striker’s end.

Douglas Jardine was born on October 23, 1900, in Malabar Hill, Bombay, to Scottish parents. I visited Jardine’s and Tiger’s old school, Winchester College, and can confirm what Frith says: “Pataudi the younger exacted some sort of revenge for his father’s treatment by bettering Jardine’s batting record at Winchester College with 1,068 runs in 1959, though Jardine did not live to know it.”

Frith writes about how the Bodyline series led to a near breakdown of relations between Australia and England: “Bodyline bowling was worrying on two levels. Physically, it was aimed at Australian throats. Figuratively, the ‘mother country’ seemed to be hitting below the belt.” It could all happen again.

Great ideas

There was a time when I hoped that Jitesh Gadhia would become a journalist. Instead, he turned very successfully to investment banking and, in 2016, David Cameron elevated him to the House of Lords. Jitesh’s idea last year, of a khadi poppy to mark Remembrance Sunday and honour the crucial contribution of Indian soldiers in the two World Wars, will be continued this year in an even bigger way by the Royal British Legion. Jitesh is now helping to draw up ambitious plans to mark the 150th anniversary of MK Gandhi’s birth on October 2. “I have been researching his footprint in the UK,” Jitesh tells me. “He came to the UK on five occasions.” These were in 1888-1891, 1906, 1909, 1914 — when he stayed for three months and helped the British war effort — and finally in 1931 for the Round Table Conference.

I did not know until Jitesh told me that on October 23, 1931, Gandhi addressed the boys at Eton College before going to a meeting at Oxford University. “He stayed overnight at the Master’s Lodge at Balliol,” says Jitesh. Both Oxford and Cambridge are likely to organize anniversary events, along with Kingsley Hall in the East End of London.

Jitesh, who gifted a copy of the Rig Veda to the Lord’s library upon becoming a peer, argues: “India has not been fully able to cultivate the aura of Gandhi. In a world where nations are competing to wield soft power, Gandhi is right at the apex when it comes to wielding soft power. He influenced so many leaders, from Martin Luther King to Nelson Mandela. He was probably the most successful NRI that India has ever produced.”

Well done

The hopes of Indians, as far as the BBC’s very popular The Great British Bake Off is concerned, rests this year on Priya O’Shea, a 34-year-old marketing consultant from Leicester, who is one of 13 contestants. She had first downloaded the application form for the show in 2012, “the year I got married”, and tried unsuccessfully to be selected last year. Indians have excelled in the past. The Calcutta boy, Rahul Mandal, a 32-year-old research scientist, won the contest last year, as did a Bangladeshi mother of three, Nadiya Hussain, in 2015. The Mumbai girl, Chetna Makan, was a semi-finalist in 2014.

Amit Roy

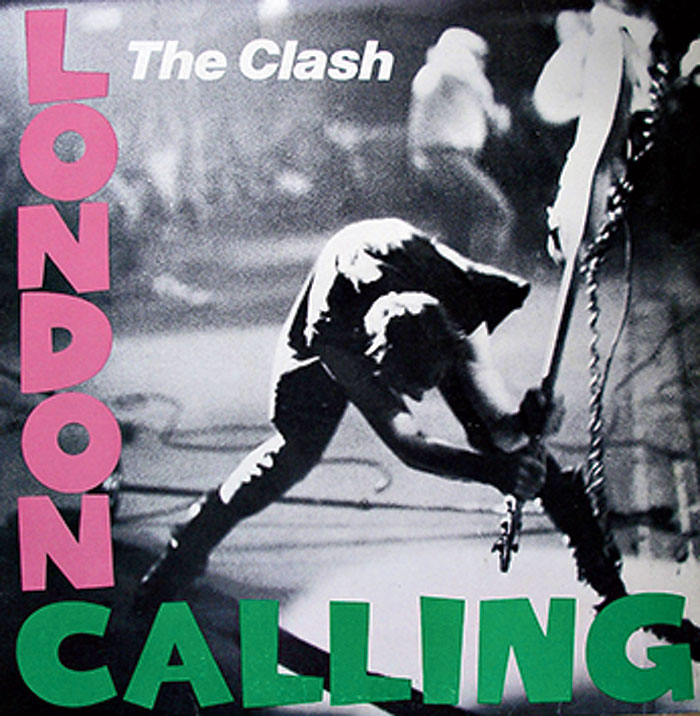

Clash London Calling Lp Cover Patrik Tschudin, Flickr

Footnote

More than 100 personal items belonging to the iconic English rock band, The Clash, including a broken guitar, will be displayed at an exhibition at the Museum of London. The Fender Precision bass belonged to Paul Simonon, who smashed it on stage at The Palladium in New York on September 21, 1979. The image, featured on the cover of their bestselling album, London Calling, is ranked as “the greatest rock photo of all time”.