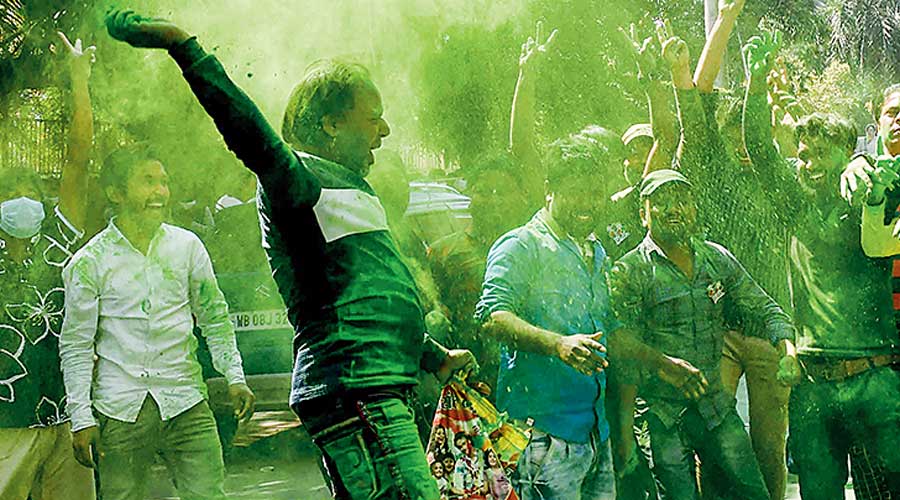

With the national focus on the five assembly elections — particularly in the all-important state of Uttar Pradesh — it is understandable that the recent round of elections to municipalities and other urban bodies in West Bengal has received only the most casual of attention outside the state. To add to its clean sweep of the Calcutta Municipal Corporation polls last December, the All India Trinamul Congress of Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee registered emphatic wins in the municipalities of Siliguri, Asansol, Chandernagore and Bidhannagar, decimating both the Bharatiya Janata Party and the once-powerful Communist Party of India (Marxist). The pattern looks set to be repeated in the elections to the municipal boards of the smaller towns, scheduled at the end of the month.

The AITC’s political stranglehold over Bengal is undeniable. However, it may be instructive to look at the circumstances that have enabled it to effect a transition from dominance to exercising a near-monopoly of political power.

That the BJP, which appeared to be suffering from a problem of plenty during last year’s assembly election, encountered serious problems in securing credible candidates for the urban body elections is well-known and has been exhaustively reported in the local media. Less publicized, however, are the challenges that the main Opposition party has faced on the ground.

A case study of a BJP activist in a small town in Hooghly district is revealing. The lady in question has been active in the party since about 2017. A single mother living largely off her modest inheritance, she was a doughty street fighter and was regarded within the party as someone with potential. Last month, she was chosen to be the BJP candidate from her home ward, a locality where she was a known figure. She dutifully filed her nomination and began the process of campaigning. It was then that her problems began.

First, her closest friend and political associate was accosted in the streets and mercilessly thrashed. Subsequently, one night, local muscle men of the ruling party arrived at her doorstep and delivered a clear message: to withdraw her nomination or face the consequences. Accustomed to threats, she initially adopted a confrontational stand. That was the signal for her tormentors to rush into her house, pick up her toddler son, and walk away. She raised a hue and cry and in the ensuing commotion the abduction of the child was averted. But her political rivals left with the warning that next time she wouldn’t be so lucky. The next morning, she withdrew from the contest.

Political violence has been endemic in West Bengal since 1967. Intimidation of opponents, including chasing them away from their homes and even murder, was a feature of the Congress rule from 1972 to 1977 and the Left Front’s dominance from 1977 to 2011. The state enjoyed a brief spell of genuine political competition from 2011 to last year’s assembly election. Since May 3, 2021, however, all restraint has been abandoned as local AITC leaders have made a concerted bid to convert West Bengal into an Opposition-free or, rather, a BJP-free zone. It will probably be no exaggeration to suggest that this climate of targeted fear has led to a section of the BJP either becoming politically inactive or switching sides. There are also stray indications that part of the gap left in the Opposition space is being filled up by the CPI(M), a party with an organization and ecosystem but limited public support.

On its part, there are indications that the state BJP, too, has retreated into a shell. The spate of inner-party feuding has resulted in most of its planned activities being reduced to token flag-waving. Even the spirited campaigning by the leader of the Opposition, Suvendu Adhikari, has met with limited success owing to the larger demoralization within the support base of the BJP. The party is now dependant on its national ratings to lift its spirits in Bengal.

The absence of any worthwhile Opposition in the state has, in turn, triggered a mood of brazenness within the AITC. The past few months have witnessed the state administration going the extra mile in displays of partisan conduct. The assembly Speaker’s decision to not disqualify Mukul Roy from membership on the grounds that he was still in the BJP must rank among the more unusual pronouncements by a presiding officer. On its part, the administration now seems more willing to move from nominal bias to express partisanship — what has been called the ‘ruler’s law’.

Simultaneously, a more confident AITC has moved from confronting the Opposition to settling factional scores. In every district, the ruling party is a deeply divided house with factional leaders bad-mouthing rivals quite openly and their battles occasionally taking a violent turn. In terms of personal conduct, some AITC leaders have shed all pretence of rectitude that is expected from public representatives.

In recent days, the spotlight has been turned on the supposed tensions between the chief minister and her nephew, Abhishek Banerjee. That the two have very different styles of functioning isn’t in any doubt. Mamata’s politics is based on old-fashioned instinct and teamwork whereas the nephew has adopted a more corporate approach towards matters such as resource mobilization. Additionally, while the chief minister banks on her party satraps for sustenance and strategy, Abhishek seems dependant on political consultants. However, the reason why these two diametrically opposite approaches were allowed to run in parallel was the belief that the AITC’s position in Bengal is unassailable. This is a risky assumption to operate on in a democracy where — as the Left Front learnt to its cost — the smallest of incidents can suddenly escalate into something politically unmanageable.

What should also worry the ruling party of the state is the steady accumulation of grievances in a climate of economic stagnation. For the moment, many of the outstanding issues have been sought to be covered up with payouts to targeted groups and the state of permanent celebrations. But there could be a vicious backlash if Opposition politics finds a face and a focus.