With time and greater awareness of social demarcations and power structures, expressions that were casually used in everyday communication and literary writing in the past have been dropped or altered. Feminist, anti-racial, anti-caste and LGBTQIA+ movements have contributed hugely to these much-needed transformations. Though we have some way to go before we live as equals and with a respect that is untainted by ingrained divisions, we have indeed come a long way from the times when whatever the socially mighty said was accepted unquestioningly. But the constant need to proclaim our ‘correctness’ has stunted the possibility of the socially privileged transforming at our very core. Somewhere built into this reactive defence of our kin is the instilled belief that we are not capable of doing bad things. Those amongst us who do are considered aberrations or misinterpreters. In other words, our entire cultural system is as perfect as it can get. This is the reason we believe we are placed on the top of the social food chain. Due to a generationally injected cultural belief of ethical superiority, we are unable to be unreservedly self-critical or re-investigate our cultural heroes with eyes wide open.

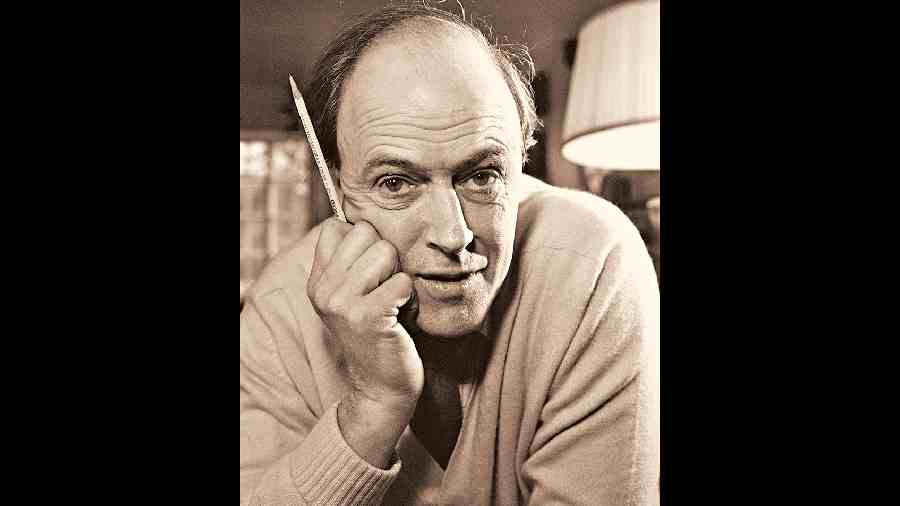

This is not just about acknowledging the past. Even if that is done, the follow-up question is more complicated. What do we do about it? My use of ‘we’ is in itself tricky. The recent questioning of Roald Dahl’s words brings this conversation back to the fore. Being a twentieth-century, modern writer of primarily children’s books, one would think it is probably easier to confront the problem. But, as we have seen, it is not. Can we change his words? If yes, to what extent? Who draws that line? What about the question of creative independence? What happens if, tomorrow, a set of powerful people with regressive beliefs reconfigure phrases of a catholic and inclusive writer?

There is also the aesthetic question. Irrespective of how careful one is, replacing words, phrases and lines changes the literary nature of the passage, poem or song. Unless carried out by the writers themselves, this is an infringement on the aesthetics of expression. It is very hard for us to create any form of common standard regarding the extent of changes that can be allowed or how much of a change retains the ‘original’ flavour. We could, of course, argue that the ‘original’ sensibility need not remain. After all, that is what we are questioning. Nevertheless, this is a sticky wicket.

In the Indian context, literary antiquity and its deeply entrenched connection with religiosity and socio-cultural mores make it that much harder. We need to go beyond the unreasonable and anachronistic demand for modern social sensitivity from an ancient writer and engage. Unfortunately, as we saw recently, when the words of Tulsidas were called out as casteist, the faithful raised the drawbridge and prepared to protect their religious fortress.

Recently, at a public interaction, a young musician asked me a similar question about a composition by the great Carnatic composer, Tyagaraja. This was also a musical quandary. The musically exquisite composition had a pejorative reference to ‘low-caste’ people. If the musician did not know the meaning of the words, he would have continued to enjoy its musicality and rendered the song with pleasure. Now that he knew the meaning, he was extremely uncomfortable. Usually when any such question is raised, music teachers and scholars either provide excuses for Tyagaraja or say that we should understand ‘low caste’ as a reference to people with low moral values. They are oblivious to how such defensive reinterpretations make things worse. Probably having heard these explanations, the musician asked me if we could alter that line in a manner that would suit today’s social standards. My response was that he should do nothing with the composition and simply avoid rendering it. He was unsatisfied, maybe even disappointed, with my answer because the musician in him wanted to sing the song. This is not very different from a reader of Dahl marvelling at the world he created but unable to reconcile the unacceptable usages, or a reciter of “Ramcharitmanas” not knowing what to do with the passages that disturb him.

But it is also true that we do not take a consistent position on this issue. There are certain words that have been socially dismissed. The use of those terms has been removed from writings and singings. Authors themselves have awakened and changed expressions. Therefore, in the mix is also the question of choice. The basis on which choices are made with regard to what is unacceptably offensive is not definite. As much as we claim that all social struggles for equality are inter-connected, within the rumble and tumble of activism there is always a battle for attention and resources. The extent of political presence of the various socio-cultural movements determines which takes priority. If the LGBTQIA+ movement has a louder voice than the body shaming group, those words will be changed sooner. As ugly as this sounds, one cannot deny that there is a hierarchy of priorities. This tussle is also convenient for the privileged. We use it to pit one group against the other and, at the same time, take the moral high ground as progressive reformers.

Some years ago, I wrote a piece on a similar theme. In that, I came to the provisional conclusion that one should leave works of art from the past as they are and let the messiness of the creation influence our receiving of the work. I was making the point that the contradictions will tutor us on the gorgeous and grotesque in a far more nuanced manner. We will learn that one is never exclusive of the other; they exist only because of the other. It was a reflection of who we are as people — complex, beautiful, limited and offensive. I was hoping that this would help demolish the belief in any form of purity.

While my argument seems sensible philosophically, there is an entrenched flaw. The person making the argument, that is I, am not the target of any of those linguistic usages. I have never felt the pain, shame, anger, oppression that they trigger within. To me, this is an intellectual question that I can deal with the detachment of impersonality. When I used the word, ‘we’, earlier in this essay, I endowed upon the privileged the right to participate in the question, ‘What do we do about it?’ This was also an error. What should follow acknowledgement is not action but active listening. It is people from communities that are affected by these expressions that must take the lead in resolving these knotty questions. They have been victims of normalised abuse and ridicule and, hence, the power to argue, debate and change must be theirs. This is not political correctness or woke-ism; it is human evolution in sensitivity. This imbroglio has no consummate answer. What we can hope for is that every step will be conscientiously forward moving. But for that to happen, we must impartially question everything we read, recite and sing.

T.M. Krishna is a leading Indian musician and a prominent public intellectual