Liberalism privileges criticism and dissent. Several statements from the writings of modern Indian thinkers can be scrutinized against the background of the liberal framework. One such statement is: “I am against conversion whether it is known as shuddhi by Hindus, tabligh by Mussulmans or proselytizing by Christians.” This quote from Mahatma Gandhi reflects the wisdom of Jesus Christ and the Buddha.

There are two levels here. One is Gandhi’s views on conversion. The second is the temporal order or the underlying sequence of what is referred to in the statement’s first, second, and third parts. Turning towards the underlying temporal order reveals a moral virtue: internal criticism preceding the criticism of others. This sequence is at the heart of the statement and cannot be changed.

Liberal philosophers like J.S. Mill recommend relentless criticism of ideas, including those held by the majority, to ensure objectivity in public life. The underlying sequence here emphasizes the right to criticize others and, at the same time, be criticized by others. The other criticism is self-criticism, which Karl Popper recommends in The Poverty of Historicism. This criticism is directed at oneself and is not about the other.

Internal criticism is different from both criticism and self-criticism. With internal criticism, the self turns towards oneself at the very moment of criticizing the other. The other, therefore, becomes a catalyst. At that moment, one understands the other through oneself, thus enhancing one’s knowledge. Moral cleanliness, too, elevates moral status. This temporal ordering is not only different but also unique.

The moral virtue derived from the temporal sequence forms a larger category in this statement. Gandhi’s view on conversion is one part of this category. Having identified this moral virtue, let me extend its purview in two ways.

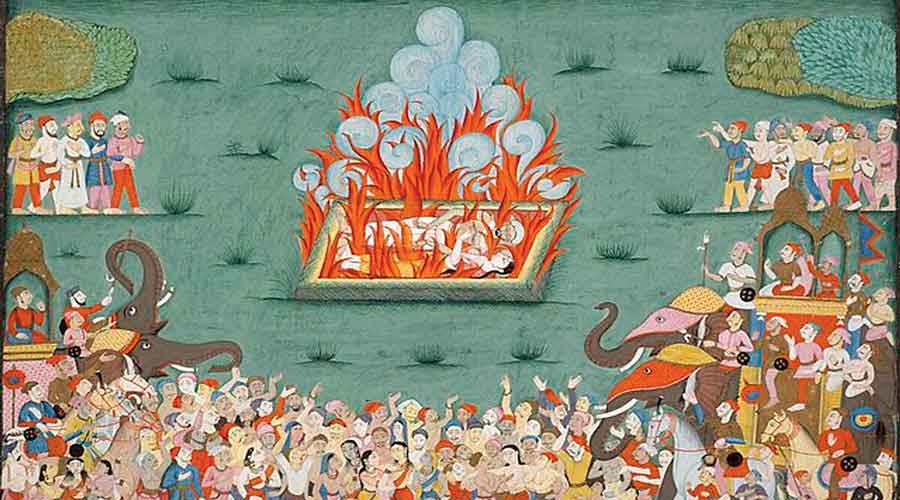

One, internal criticism is not only a norm but also provides a frame or a perspective to understand the writings of modern Indian thinkers. An overlapping idea that permeates the writings of Swami Vivekananda, Sri Aurobindo, Mahatma Gandhi, B.R. Ambedkar, albeit in varying degrees, is the acceptance of evils within Indian society. This includes poverty and backwardness, the practice of untouchability, superstitions, caste hierarchy and discrimination, child marriage, the practice of sati, to name a few.

Here it is necessary to note that the list of these social evils was prepared by the enemy — the British rulers and their scholars. These were neither researched by freedom fighters nor identified as negative in the Indian tradition. However, the purpose of the British in preparing this list was to ‘legitimize’ their rule after assuming control from the East India Company.

The ingenuity of the Indian leaders, however, lay in accepting the list and repurposing it to suit their objectives. They treated this list as an exercise in problem-solving and came up with various solutions. This process of internal criticism preceded their fight against the British. The moral cleansing amidst colonial oppression helped them gain a better understanding of Indian society and elevated the moral status of the Independence movement. The movement was strengthened by the immense support and participation garnered by the Indian leaders across different sections of the population. This would not have been possible had they not confronted the internal evils first.

Two, this moral virtue can be used to assess the current problems in India. For instance, internal criticism can better understand the move towards disinvestment and privatization of public sector institutions. Here, the internal criticism of the public sectors needs to precede the criticism of privatization.

A list of the problems and anomalies within the public sector can first be prepared, and suggestions offered to resolve them. The focus on the present is more important than basking in past achievements. These invaluable institutions played a crucial role in building post-Independence India but are in danger of becoming dead relics, ineffectual in the present unless we re-evaluate and revive them.

Corruption is destroying public institutions like termites. In addition, those who work in these institutions often do not see the relationship between their remuneration and their expected work in return. They take their jobs for granted and become complacent. Further, while working within the public sector themselves, some endorse privatizing institutions like Air India, though they may vehemently oppose a similar decision for their own institution. So there is the government’s reason for privatizing; there is also an intra-public sector view regarding each other and internal criticism. All these can throw a better light and give a substantial understanding of these institutions’ role and function.

At a general level, there is a tendency to view modern institutions like the public sector or radical modern ideas like liberalism as frozen and outmoded, relegating them to dusty cupboards from the past. This is disguised orthodoxy, and we should not ignore this temporal mismatch. These radical ideas will not survive for long in the past tense but can become valuable assets within the temporality of the present. Internal criticism is an essential moral virtue that can help replenish these modern ideas and institutions, making them relevant to the present.

So, in addition to dissent, criticism and self-criticism, internal criticism is an important moral norm. This norm also provides a better framework to understand the writings of modern Indian thinkers where internal criticism of evils in Indian society preceded their fight against colonialism. Further, this norm can also enable us to understand individual and social actions as well as the functioning of public institutions and spaces.

(A. Raghuramaraju teaches philosophy at the Indian Institute of Technology Tirupati)