The deaths within days of one another, in September, of the former ambassadors, K.P.S. Menon, and Satyabrata Pal, are extinguishings. But of much more than of individual lamps. Being the kind of persons they were and representing what is so inadequately but truthfully called an ethos, their going is like the darkening of a whole chandelier as its last drop-pendants go out.

Last… why? Is the Indian Foreign Service not an order in perpetuity and are we not served by a galaxy of diplomats?

So we are of course, and thank the goodness of our luck for that.

And yet their going is a going of something that is becoming scarce. Diplomacy is changing worldwide and Indian diplomacy rather rapidly so. K.P.S. Menon and Satyabrata Pal belonged to a style of diplomacy in which the person was no less important than the type, the individual mattered as much as her or his skills. Both filled their professional roles with their personal statures, not the other way around. When they represented India, as Menon did in Bangladesh, Egypt, Japan and China and Pal in South Africa and Pakistan, they did so not as diplomatic digits but as persons carrying within them what can be only described as India’s curious and flickering light — a blend of flame and torch, energy and luminosity emanating from a wick that can sometimes burn low and sometimes tall. Their minds were theirs, their mission was India’s. They belonged to the generation of diplomats that took pride in representing India not because India was a case to be presented but was a privilege to represent.

There was a time, until not all that long ago, when an Indian even mildly interested in our external relations could say who our ambassador or high commissioner was in, say, Moscow, London or Washington. And even more so, in Beijing or Islamabad. For all of them were in themselves something apart from being representatives of India.

In the Kremlin, the philosopher-ambassador, Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, was something of a wonder. “I would like to meet,” the well-informed Stalin is believed to have said, “the Ambassador who spends all his time in bed — reading.” Radhakrishnan’s biographer and son, Gopal, tells us that when Stalin did meet Nehru’s ambassador, he found his slim, tall visitor advising him to explore the possibility of détente. On Stalin’s saying he could not do that by himself, the ambassador said it takes two to make a quarrel but one can stop it.

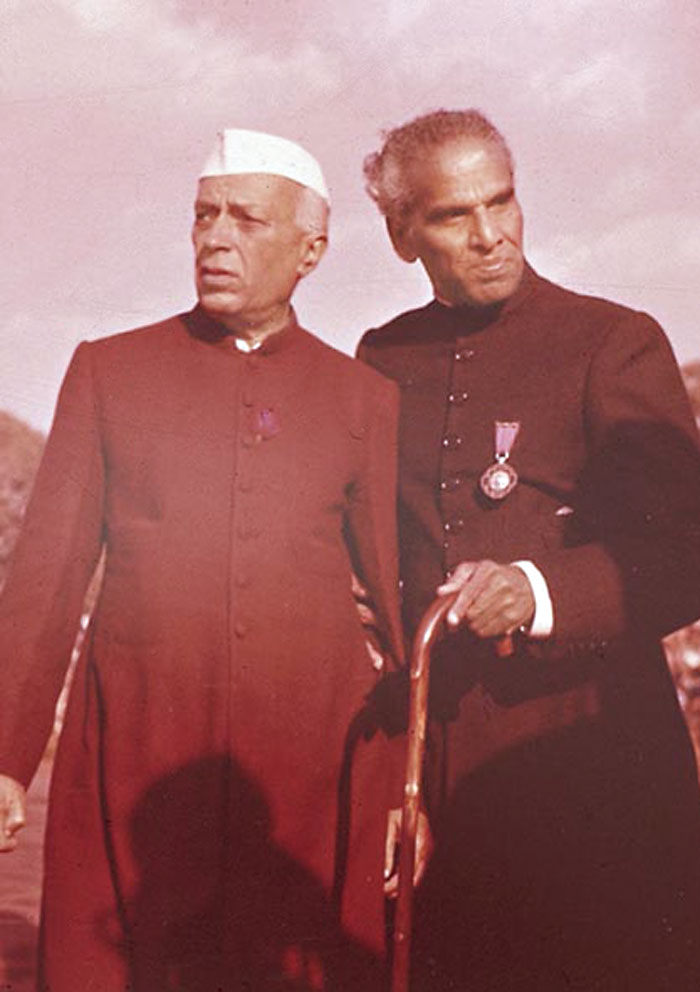

V.K. Krishna Menon (picture) was not by instinct a diplomat. On the contrary, in London, as secretary of the India League right up to the day he was appointed India’s first high commissioner to Great Britain, he was a gadfly, buzzing away, to promote India’s independence, in the words of Harold Laski, as part of “the end of imperialism everywhere”. When Laski died, Menon did what only one like him would: he placed his Rolls-Royce at the disposal of the Laski family for the funeral at Golders Green, attended by the prime minister and many ministers, socialists, scholars, students. And he stood discreetly by as committal over, Chopin’s “Funeral march” was played and the gathering dispersed. That was representation.

Sri Prakasa is not a name many will place today. The barrister son of the scholar and theosophist, Dr Bhagwan Das, Sri Prakasa was India’s first high commissioner to Pakistan. A friend of both Nehru and of Jinnah, he carried on a conversation with the new nation’s first governor general on the future of the now forlorn Jinnah House on Bombay’s Malabar Hill, helping his host realize his dream. Jinnah implored the Indian high commissioner to tell the then prime minister, Nehru, to hold the house for its now evacuated owner. Sri Prakasa writes in his memoirs that he asked Jinnah: “May I tell the Prime Minister that you are wanting to go back there?” Jinnah replied, “Yes, you may.” And so he told Nehru that and Nehru obliged, letting the house to the British high commission for a rental that Jinnah indicated, an arrangement that lasted briefly but tellingly.

India’s diplomatic representatives in the Nehru era were men and women who brought weight to their positions, height to their offices. Nehru took a lively personal interest in each induction, interviewing the entrants after their appointments had been recommended by the Union Public Service Commission and before their appointments. Thomas Abraham, for instance, recalled how in 1952 he and his peers in that year’s ‘batch’ met the prime minister individually even if for no more than 10 to 15 minutes. “You must be a Syrian Christian,” Nehru said to Abraham as soon as the young man sat down. And then he asked him what he had been doing with himself. Abraham said he had been a journalist. Nehru then asked if he knew any Hindi. “I picked up some in Bombay when I was working there,” Abraham said. “Then you must un-pick it, for Bombay Hindi is terrible…” They then discussed Korea, the hot topic of the time, with Nehru trying to see the American perspective and Abraham offering the opposite viewpoint.

There was courtesy between them. And trust. But there was also frankness. Because what was being ‘prepared’ was India’s representation, not propaganda. And that required understanding, not brain-washing. Values which informed our freedom struggle went into the shaping of our foreign policy. At the Asian Relations Conference (March-April 1947) at which leading players from this part of the world were present, these values were endorsed. They may be called the Asokan, Akbaresque and Nehruvian core. Non-alignment, our position on Palestine, on Tibet, on Afro-Asian unity, on disarmament, grew out of that vision. That policy looked at the world’s future, its future in conversation if not in concord, in negotiation if not in absolute peace. It also looked at the future in terms of equality between nations, not in terms of power-centres, regional or global.

India’s ambassadors in subsequent years have not been any less. They have moulded India’s diplomacy, shaped bilateralism in the highest sense of mutualities, political, cultural and intellectual no less than the currently preponderant — techno-commercial.

A seminal work — Values in Foreign Policy: Investigating Ideals and Interests has just appeared. Edited by the former Indian foreign secretary, Krishnan Srinivasan, James Mayall and Sanjay Pulipaka, it tells us in panoramic essays where values stand in the world of diplomacy, where foreign policy can make all the difference between a future in shared life or — the alternative need hardly be mentioned.

In our times when the menace of terrorism, with non-State players threatening the physical security of millions, climate change taking a toll in terms of livelihood security, and mass migrations running against barriers, India’s ambassadors are literally standing in the front line or the cross-hairs of global crises. In a sensitive Afterword to Hardeep Singh Puri’s book, Perilous Interventions, the ambassador, Youssef Mahmoud, former special representative of the United Nations secretary general, says: “…countries in the grip of rising right-wing nationalists, who, heedless of past lessons, believe that building high fences, and turning away desperate refugees will make their countries safer.” It is diplomatic voices like Mahmoud’s that show the way.

Ambassadors by their very training cannot and do not speak for themselves in their host countries. But they can and must speak their minds at home, in the confidence that their calling requires. They must, as diplomats, give precedence to the option for negotiation, discussion, dialogue. Not belligerence, bellicosity, ballistics. They must quell, not fan the fires of prejudice; must douse, not inflame suspicion. They are diplomats, not politicians in diplomatic attire. If generals speak like diplomats, nothing is lost except the army’s time. But when diplomats speak like generals, the result is disastrous.

To do this they have to be themselves. More importantly, they have to be allowed, encouraged to be themselves. In the final analysis, only that country will have for its ambassadors men and women with minds of their own, which value the individual in its polity, its society. A country which does not see the individual as distinctive, individual variations as valuable and social diversity as precious will want its ambassadors to be not Ambassadors Extraordinary but Ambassadors Made to Order. Which is why the loss of K.P.S. Menon and Satyabrata Pal is so diminishing, so eroding of us at our core.