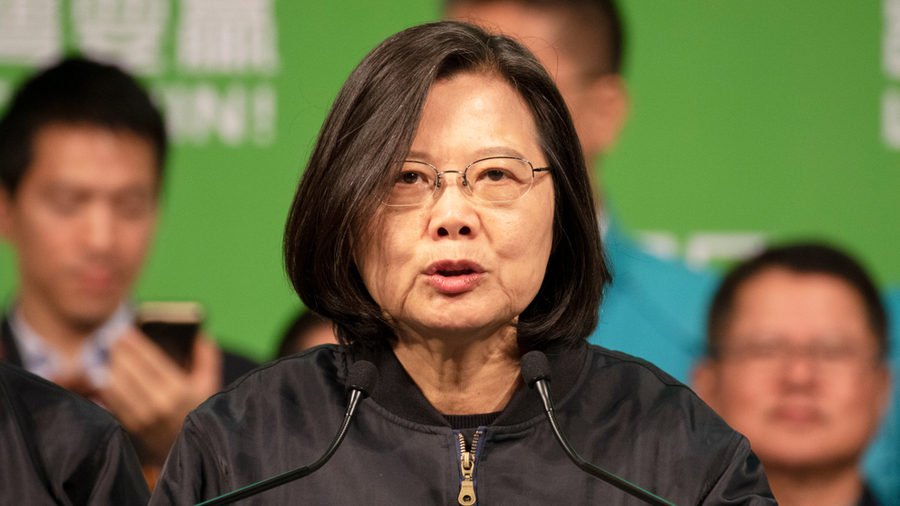

What’s Tsai Ing-wen’s favourite Indian dish? If you’ve been following the Taiwan president on Twitter, you’ll know she loves chana masala and naan. Her favorite Indian drink? “#[C]hai always takes me back to my travels in #India, and memories of a vibrant, diverse & colorful country,” she wrote on the social media platform on October 15.

It was neither a momentous day in India-Taiwan relations, nor a special occasion on New Delhi’s diplomatic calendar. It was a not-so-subtle cultural pinprick targeted at Beijing, meant to underscore the growing warmth between India and Taiwan at a time when both are in the midst of tense military stand-offs with China.

Indeed, the past few weeks have seen engagements between India and Taiwan at an unprecedented speed, even as New Delhi continues to negotiate with Beijing for a resolution of their current border crisis in Ladakh. It’s both legitimate and understandable for India to utilize ties with Taiwan to send a message to China. But in any card game, overplaying one’s hand can prove dangerous.

In recent weeks, three Taiwanese firms, including the electronics manufacturing giant, Foxconn, have announced plans to invest $900 million in India. Earlier in the year, when the Covid-19 pandemic broke out, Taiwan was among India’s first foreign friends to offer medical assistance — even though New Delhi does not formally recognize Taipei diplomatically. Under Beijing’s ‘One China’ policy — which India adheres to — all nations must choose between China and Taiwan as diplomatic partners.

New Delhi, too, has reciprocated this recent warmth from Taiwan. Ahead of Taiwan’s National Day, October 10, the Chinese embassy issued a warning to Indian media houses urging them to refrain from publicizing the occasion and asking them to desist from referring to Tsai as the president of Taiwan since Beijing considers the self-governing region as a part of China. But the Indian foreign ministry publicly defended the right of Indian journalists and media houses to highlight Taiwan’s National Day. And on October 10, the street outside the Chinese embassy was plastered with posters celebrating Taiwan’s National Day. The posters bore the name of the Delhi BJP leader, Tajinder Pal Singh Bagga. Those posters would never have been allowed in the vicinity of the embassy without the government’s tacit approval: just ask Tibetan activists who have repeatedly been barred from protesting outside the Chinese diplomatic mission. Recent reports now suggest India is contemplating a trade deal with Taiwan. Those unconfirmed reports have predictably sparked criticism from Beijing.

There’s nothing wrong in India and Taiwan courting each other. Even without China in the equation, the two have complementary synergies that could benefit both. Taiwan is an advanced economy with technological advantages — especially in electronics — that India could benefit from. India is a giant market that Taiwan would love to tap into a lot more.

China’s growing friction with both Taiwan and India simultaneously has further catalyzed the motivation for Taipei and New Delhi to embrace each other more tightly. Beijing’s planes have in recent months engaged in multiple Top Gun-like manoeuvres with American jets — the United States of America is Taiwan’s biggest security provider — in the Taiwan Strait that separates the island from China. Beijing has also upgraded military exercises focused on retaking Taiwan. Meanwhile, India struggles to convince China to move its troops back from parts of Ladakh that the People’s Liberation Army has grabbed in recent months. There are no signs of their border crisis easing up.

But for all the confluence in interests with Taiwan, India needs to be mindful of some difficult realities. There’s nothing worse than holding out a threat, either publicly or through ‘unnamed sources’, without having the ability — and the heart — to follow through. Already, some senior diplomats within the foreign ministry are trying to distance the government from the reports of a trade deal with Taiwan. The Narendra Modi government is indeed strengthening its military partnerships with other countries unhappy with China — Australia, for instance, will join India, the US and Japan in the next iteration of their Malabar exercises. But it also knows that at the end of the day, no amount of Taiwanese trade and investment can make up for what India could lose with China, one of India’s largest trade partners.

For years — whether with the Dalai Lama and Tibet in the past or Taiwan now — successive Indian governments have needled China on its political weaknesses but then backed off when push came to shove. The economics of the relationship are a central part of that equation. Is the Modi government willing to forego that economic partnership? Does it have a backup plan? Is it truly ready — and not just in terms of rhetoric — for a military escalation with China? Sure, it has banned TikTok. But Taiwan and TikTok are not comparable for Beijing: one is central to its identity as China; the other an upstart app that’s useful but replaceable.

In the past, the failure of Indian governments to go through with threats issued to China has bolstered Beijing’s conviction that New Delhi is a paper tiger. New Delhi needs to make sure that with Taiwan, it doesn’t bite off more than it can chew.